By Paul Driessen

What if we applied corporate standards to the “science” that is driving global warming policy?

Imagine the reaction if investment companies provided only rosy stock and economic data to prospective investors; manufacturers withheld chemical spill statistics from government regulators; or medical device and pharmaceutical companies doctored data on patients injured by their products.

Media frenzies, congressional hearings, regulatory investigations, fines and jail sentences would come faster than you can say Henry Waxman. If those same standards were applied to global warming alarmists, many of them would be fined, dismissed and imprisoned, sanity might prevail, and the House-Senate cap-and-tax freight train would come to a screeching halt.

Fortunately for alarmists, corporate standards do not apply - even though sloppiness, ineptitude, cherry-picking, exaggeration, deception, falsification, concealed or lost data, flawed studies and virtual fraud have become systemic and epidemic. Instead of being investigated and incarcerated, the perpetrators are revered and rewarded, receiving billions in research grants, mandates, subsidies and other profit-making opportunities.

On this bogus foundation Congress, EPA and the White House propose to legislate and regulate our nation’s energy and economic future. Understanding the scams is essential. Here are just a few of them.

Michael Mann’s hockey-stick-shaped historical temperature chart supposedly proved that twentieth century warming was “unprecedented” in the last 2000 years. After it became the centerpiece of the UN climate group’s 2001 Third Assessment Report, Canadian analysts Ross McKitrick and Steve McIntyre asked Mann to divulge his data and statistical algorithms. Mann refused. Ultimately, Mc-Mc, the National Science Foundation and investigators led by renowned statistician Edward Wegman found that the hockey stick was based on cherry-picked tree-ring data and a computer program that generated temperature spikes even when random numbers were fed into it here.

This year, another “unprecedented” warming study went down in flames. Lead scientist Keith Briffa managed to keep his tree-ring data secret for a decade, during which the study became a poster child for climate alarmism. Finally, McKitrick and McIntyre gained access to the data. Amazingly, there were 252 cores in the Yamal group, plus cores from other Siberian locations. Together, they showed no anomalous warming trend due to rising carbon dioxide levels. But Briffa selected just twelve cores, to “prove” a dramatic recent temperature spike, and chose three cores that “demonstrated” there had never been a Medieval Warm Period. It was a case study in how to lie with statistics here.

Meanwhile, scientists associated with Britain’s Climatic Research Unit (CRU) also withheld temperature data and methods, while publishing papers that lent support to climate chaos claims, hydrocarbon taxes and restrictions, and renewable energy mandates. In response to one request, lead scientist Phil Jones replied testily: “Why should I make the data available, when your aim is to try and find something wrong with it?” Of course, that’s what the scientific method is all about - subjecting data, methods and analyses to rigorous testing, to confirm or refute theories and conclusions. When pressure to release the original data became too intense to ignore, the CRU finally claimed it had “lost” (destroyed?) all the original data (here).

The supposedly “final” text of the IPCC’s 1995 Second Assessment Report emphasized that no studies had found clear evidence that observed climate changes could be attributed to greenhouse gases or other manmade causes. However, without the authors’ and reviewers’ knowledge or approval, lead author Dr. Ben Santer and alarmist colleagues revised the text and inserted the infamous assertion that there is “a discernable human influence” on Earth’s climate (here).

Highly accurate satellite measurements show no significant global warming, whereas ground-based temperature stations show warming since 1978. However, half of the surface monitoring stations are located close to concrete and asphalt parking lots, window or industrial-size air conditioning exhausts, highways, airport tarmac and even jetliner engines - all of which skew the data upward. The White House, EPA, IPCC and Congress use the deceptive data anyway, to promote their agenda (here).

With virtually no actual evidence to link CO2 and global warming, the climate chaos community has to rely increasingly on computer models. However, the models do a poor job of portraying an incredibly complex global climate system that scientists are only beginning to understand; assume carbon dioxide is a principle driving force; inadequately handle cloud, solar, precipitation, ocean currents and other critical factors; and incorporate assumptions and data that many experts say are inadequate or falsified. The models crank out (worst-case) climate change scenarios that often conflict with one another. Not one correctly forecast the planetary cooling that began earlier this century, as CO2 levels continued to climb.

Al Gore’s climate cataclysm movie is replete with assertions that are misleading, dishonest or what a British court chastised as “partisan” propaganda about melting ice caps, rising sea levels, hurricanes, malaria, “endangered” polar bears and other issues. But the film garnered him Oscar and Nobel awards, speaking and expert witness appearances, millions of dollars, and star status with UN and congressional interests that want to tax and penalize energy use and economic growth. Perhaps worse, a recent Society of Environmental Journalists meeting made it clear that those supposed professionals are solidly behind Mr. Gore and his apocalyptic beliefs, and will defend him against skeptics (here).

These and other scandals have slipped past the peer review process that is supposed to prevent them and ensure sound science for a simple reason. Global warming disaster papers are written and reviewed by closely knit groups of scientists, who mutually support one another’s work. The same names appear in different orders on a series of “independent” reports, all of which depend on the same original data, as in the Yamal case. Scientific journals refuse to demand the researchers’ data and methodologies. And as in the case of Briffa, the IPCC and journals typically ignore and refuse to publish contrary studies.

Scandals like these prompted EPA career analyst Alan Carlin to prepare a detailed report, arguing that the agency should not find that CO2 “endangers” human health and welfare, because climate disaster predictions were not based on sound science. EPA suppressed his report and told Carlin not to talk to anyone outside his immediate office, on the ground that his “comments do not help the legal or policy case for this decision,” which the agency supposedly would not make for several more weeks (here).

The endless litany of scandals underscores the inconvenient truth about global warming hysteria. The White House, Congress and United Nations are imperiling our future on the basis of deceptive science, phony “evidence” and worthless computer models. The climate protection racket will enrich Al Gore, alarmist scientists who get the next $89 billion in US government research money, financial institutions that process trillion$$ in carbon trades, and certain companies, like those that recently left the US Chamber of Commerce. For everyone else, it will mean massive pain for no environmental gain (here).

Still not angry and disgusted? Read Chris Horner’s Red Hot Lies, Lawrence Solomon’s Financial Post articles, Steve Milloy’s Green Hell, and Benny Peiser’s CCNet daily climate policy review. Then get on your telephone or computer, and tell your legislators and local media this nonsense has got to stop. It may be that none dare call it fraud - but it comes perilously close.

By Roger Pielke Jr.

As the world continues to suffer a “depression” in global tropical cyclone activity with activity at 30-year lows, and hurricane forecasters try to keep busy while watching the listless Atlantic, I thought that for those who haven’t been reading this blog for the past 5 years (which I assume is most everyone) it would be worth reviewing a bit of the history of the science on hurricanes and global warming, and how that science was ignored by the IPCC.

In 2004 and 2005 (before Katrina), I led an interdisciplinary effort to review the literature on hurricanes and global warming. The effort resulted in a peer-reviewed article in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society (here in PDF ) Upon its acceptance Kevin Trenberth, a scientist at NCAR here at Boulder and the person in charge of the 2007 IPCC AR4 chapter that reviewed extreme events including hurricanes, said this in the Boulder Daily Camera (emphasis added) about our article:

I think the role of the changing climate is greatly underestimated by Roger Pielke Jr. I think he should withdraw this article. This is a shameful article. Here is what the “shameful article” concluded:

To summarize, claims of linkages between global warming and hurricane impacts are premature for three reasons. First, no connection has been established between greenhouse gas emissions and the observed behavior of hurricanes… Second, the peer-reviewed literature reflects that a scientific consensus exists that any future changes in hurricane intensities will likely be small in the context of observed variability… And third, under the assumptions of the IPCC, expected future damages to society of its projected changes in the behavior of hurricanes are dwarfed by the influence of its own projections of growing wealth and population… While future research or experience may yet overturn these conclusions, the state of the peer-reviewed knowledge today is such that there are good reasons to expect that any conclusive connection between global warming and hurricanes or their impacts will not be made in the near term.

When Trenberth called the article shameful I responded on Prometheus with this comment:

“Upon reading Kevin’s strong statements in the press a few weeks ago, I emailed him to ask where specifically he disagreed with our paper and I received no response; apparently he prefers to discuss this issue only through the media. So I’ll again extend an invitation to Kevin to respond substantively, rather than simply call our paper ‘shameful’ and ask for its withdrawal (and I suppose implicitly faulting the peer review process at BAMS): Please identify what statements we made in our paper you disagree with and the scientific basis for your disagreement. If you’d prefer not to respond here, I will eagerly look forward to a letter to BAMS in response to our paper.”

Climate change is a big deal. We in the scientific community owe it to the public and policy makers to be open about our debates on science and policy issues. We’ve offered a peer-reviewed, integrative perspective on hurricanes and global warming. I hold those with different perspectives in high regard - such diversity makes science strong. But at a minimum it seems only fair to ask those who say publicly that they disagree with our perspective to explain the basis for their disagreement, instead of offering up only incendiary rhetoric for the media. Given that Kevin is the IPCC lead author responsible for evaluating our paper in the context of the IPCC, such transparency of perspective seems particularly appropriate.

Not surprisingly the IPCC chapter that Trenberth led for the IPCC made no mention of our article, despite it being peer reviewed and being the most recently published review of this topic prior to the IPCC publication deadline (the relevant IPCC chapter is here in PDF). Even though the IPCC didn’t see the paper as worth discussing, a high-profile team of scientists saw fit to write up a commentary in response to our article in BAMS (here in PDF) . One of those high-profile scientists was Trenberth. Trenberth and his colleagues argued that our article was flawed in three respects, it was,

“...incomplete and misleading because it 1) omits any mention of several of the most important aspects of the potential relationships between hurricanes and global warming, including rainfall, sea level, and storm surge; 2) leaves the impression that there is no significant connection between recent climate change caused by human activities and hurricane characteristics and impacts; and 3) does not take full account of the significance of recently identified trends and variations in tropical storms in causing impacts as compared to increasing societal vulnerability.”

Our response to their comment (here in PDF) focused on the three points that they raised:

“Anthes et al. (2006) present three criticisms of our paper. One criticism is that Pielke et al. (2005) “leaves the impression that there is no significant connection between recent climate change caused by human activities and hurricane characteristics and impacts.” If by “significant” they mean either (a) presence in the peer-reviewed literature or (b) discernible in the observed economic impacts, then this is indeed an accurate reading. Anthes et al. (2006) provide no data, analyses, or references that directly connect observed hurricane characteristics and impacts to anthropogenic climate change.”

In a second criticism, Anthes et al. (2006) point out (quite accurately) that Pielke et al. (2005) failed to discuss the relationship between global warming and rainfall, sea level, and storm surge as related to tropical cyclones. The explanation for this neglect is simple - there is no documented relationship between global warming and the observed behavior of tropical cyclones (or TC impacts) related to rainfall, sea level, or storm surge.

A final criticism by Anthes et al. (2006) is that Pielke et al. (2005) “does not take full account of the significance of recently identified trends and variations in tropical storms in causing impacts as compared to increasing societal vulnerability.” Anthes et al. (2006) make no reference to the literature that seeks to distinguish the relative role of climate factors versus societal factors in causing impacts (e.g., Pielke et al. 2000; Pielke 2005), so their point is unclear. There is simply no evidence, data, or references provided by Anthes et al. (2006) to counter the analysis in Pielke et al. (2000) that calculates the relative sensitivity of future global tropical cyclone impacts to the independent effects of projected climate change and various scenarios of growing societal vulnerability under the assumptions of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

This series of exchanges was not acknowledged by the IPCC even though it was all peer-reviewed and appeared in the leading journal of the American Meteorological Society. As we have seen before with the IPCC, its review of the literature somehow missed key articles that one of its authors (in this case Trenberth, the lead for the relevant chapter) found to be in conflict with his personal views, or in this case “shameful.” Of course, there is a deeper backstory here involving a conflict between my co-author Chris Landsea and Trenberth in early 2005, prompting Landsea to resign from the IPCC.

So almost five years after we first submitted our paper how does it hold up? Pretty well I think, on all counts. I would not change any of the conclusions above, nor would I change the reply to Anthes et al. Science changes and moves ahead, so any review will eventually become outdated, but ours was an accurate reflection of the state of science as of 2005. However, you won’t find any of this in the IPCC.

By Ian Talley, Wall Street Journal

The head of the Congressional Budget Office on Wednesday countered Obama administration claims that a landmark climate bill would be a boost to the economy.

President Barack Obama and Senate Democrats championing the bill have said mandating greenhouse-gas caps, renewable energy and efficiency standards would be a boon to an ailing economy, creating new low-carbon industries. Millions of so-called green jobs would be created under the cap-and-trade legislation being considered in the Senate, Democrats say.

CBO Director Douglas Elmendorf warned a Senate energy panel that there would be “significant shifts” from emissions-intense sectors such as oil and refining firms to low-carbon businesses such as wind and solar power.

“The net effect of that we think would likely be some decline in employment during the transition because labor markets don’t move that fluidly,” Mr. Elmendorf said, testifying before the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee.

“The fact that jobs turn up somewhere else for some people does not mean there aren’t substantial costs borne by people, communities, firms and affected industries,” he said.

Sen. Sam Brownback (R., Kan.) expressed the fears of many lawmakers, both Democrat and Republican. “You’re talking about a massive market manipulation here on a grand scale that has significant impacts on the Midwest and the South … [including] the likelihood of us to lose a lot of jobs, a lot of businesses,” he said.

The CBO director added that although the risks of climate-related impacts on the economy were very difficult to quantify, “many economists believe that the right response to that kind of uncertainty is to take out some insurance, if you will, against some of the worst outcomes.”

The CBO estimates that the House-passed climate legislation, a template for the Senate version, would reduce gross domestic product by up to 0.75% by 2020 and 3.5% by 2050.

But Mr. Elmendorf and other senior government experts also said forecasts for economic impacts were riddled with ambiguity.

“The uncertainties are very large, even for 2020, and they get larger over time,” the CBO director said.

Two major factors that contribute to that uncertainty are the potential growth of new nuclear power and potential use of international emission credits called offsets that allow companies to invest in low-emission projects overseas.

The Environmental Protection Agency’s analysis of congressional climate legislation assumed almost 100 new nuclear power plants over the next two decades.

Sen. John McCain (R., Ariz.) questioned that assumption. “It’s a bit presumptuous to take into your calculations a significant increase in nuclear power when there’s nothing in the landscape that would indicate that that’s the case,” he told EPA senior economist Reid Harvey, who testified before the panel.

Without a solution to nuclear-waste storage, a continuing bottleneck in licensing and insufficient loan guarantees to encourage nuclear power financing, “we’re just going to repeat what’s happened in the last 20 years,” Mr. McCain said. No new nuclear power plants have been commissioned in the past two decades, and although there are more than two dozen applications for plants at the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, the government only has loan guarantee authority for about three to four new stations.

Assuming only a small increase in nuclear generation would raise the EPA’s estimates for the cost of emitting greenhouse gases by 15% alone.

Many industry officials also question the legitimacy of calculating international offsets, which will require a raft of complex international treaties and which can be very difficult to verify and prone to fraud. By eliminating the international offset assumption from their calculus, the EPA said carbon cost estimates nearly double.

The senior government experts also said the impact to the economy could easily impact different sections of the population disproportionately. The lowest-income quintile could see a positive benefit in their energy bills while the middle classes and industrial and commercial consumers would bear the burden of higher costs.

By Anthony Watts, Watts Up With That

First, I loathe having to write another story about Pen Hadow and his Catlin Arctic Ice expedition, which I consider the scientific joke of 2009. But these bozos are once again getting some press over the “science” data, and of course it is being used to make the usual alarmist pronouncements such as this badly written story in the BBC:

Click for a larger image

WUWT followed the entire activist affair disguised as a science expedition from the start. You can see all of the coverage here. It’s not pretty. When I say this expedition was the “scientific joke of 2009”, I mean it.

See the detailed Top Ten List.

Read the top ten reasons and then this nonsense BBC coverage of this so called expedition claiming Arctic to be Ice-Free in 10 Years.

Pen Hadow’s team completed an extensive survey of the Arctic ice cap. The Arctic Ocean could be largely ice-free and open to shipping during the summer in as little as ten years’ time, a top polar specialist has said. “It’s like man is taking the lid off the northern part of the planet,” said Professor Peter Wadhams, from the University of Cambridge. Professor Wadhams has been studying the Arctic ice since the 1960s. He was speaking in central London at the launch of the findings of the Catlin Arctic Survey. The expedition trekked across 435km of ice earlier this year.

Led by explorer Pen Hadow, the team’s measurements found that the ice-floes were on average 1.8m thick - typical of so-called “first year” ice formed during the past winter and most vulnerable to melting.

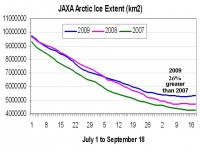

See comparison of arctic ice at minimum in 2009 versus 2007 enlarged here.

Unfortunately the data challenges this as the ice was 26% greater than 2007 with a large increase in second year ice which will become third year ice next year. The alarmists are trying to continue the hype about arctic ice going for Copenhagen.

By Gary Robbins, OC Register Science Dude

Trying to figure out whether Orange County is going to have a wet winter is something of a fool’s game. No one can consistently predict the weather and climate due to the limitations of science. And the issue becomes even tougher when forecasters are unsure whether an emerging El Nino will be weak, moderate or strong, which is what’s happening now.

Earlier this year, the U.S. Climate Prediction Center formally announced that the periodic climate change was developing in the equatorial Pacific. It initially looked to be a weak event, at best. But CPC later said it could be “moderate to strong.”

Bill Patzert, a climatologist at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, responded by saying “El Nino would El Fizzle.” And some recent CPC forecasts looked like scientists were back-pedaling a bit.

The latest CPC forecast, issued on Oct. 8, adds to the confusion. The agency says, “A majority of the model forecasts for the Nino suggest that El Nino will reach at least moderate strength during the Northern Hemisphere fall. Many model forecasts even suggest a strong El Nino during the fall and winter, but in recent months some models, including the NCEP CFS, have over-predicted the degree of warming observed so far in the Nino-3.4 region.

“Based on the model forecasts, the seasonality of El Nino, and the continuation of westerly wind bursts, El Nino is expected to strengthen and most likely peak at moderate strength.” In other words, no one has a clue as to what will really happen. Read more here. H/T Suzanne

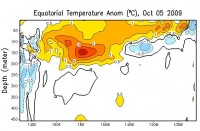

See larger image here

See the latest anomalies. The waters in the eastern areas have cooled, while warming has concentrated in the central Tropical Pacific.

See larger equatorial Pacific cross section image here. We will watch to see if westerly wind bursts take that subsurface warm pool in the west central to the east.

If that doesn’t happen and the cold east warmer central configuration remains into the winter, that is a very cold signal for the east in January. Cold PDO El Ninos tend to be relatively weak and tend to end early, as Dr. Patzert, one of the best El Nino forecasters because he considers the condition in whole Pacific, said, it could be an El Fizzle.

By Patrik Jonsson, Christain Science Monitor

How do you reconcile the early snow in Minneapolis, ski resorts already opening in Nevada, and that August chill in North Dakota with expert warnings about a warming climate?

You don’t. Why? The Earth isn’t warming right now, is why. It may even be cooling down somewhat.

Five major climate centers around the world agree that average global temperatures have not risen in the past 11 years, according to the BBC. In fact, in eight of those years, global average temperatures dipped a tad.

Yes, there have been several record heat spikes during that time period. The Southern Hemisphere this summer saw the highest land and water temperatures ever recorded, for instance. But overall? Steady as she goes.

Reasons cited range from a slightly cooling Pacific - a major global heat trap - as well as renewed questions about the sun’s role in warming (about which there is much debate). Also, it’s possible, some say, that warming itself causes CO2 levels - which are associated with warming - instead of the other way around.

As a result, “The depth of the cold of the coming winters will change the social and political climate in ways that only nature can orchestrate,” predicts meteorologist Art Horn.

To be sure, it’s way too early to close one’s ears to those who predict more global warming and sea level rises. The UN’s climate agency predicts that from 2010 to 2015 at least half the years will be hotter than the current hottest year on record, which was 1998. And as most of us know, the Earth warmed at historic rates in the latter half of the 20th century, leading to ice cap melts and ecological implications around the globe.

But the warming stall, some experts say, is giving at least some credence to the contrarian (and not always scientifically sound) notion that it may be natural and solar forces contributing as much, or more, than man-made CO2. At the very least, a delay in warming even as total CO2 emissions increase, throws some doubt on the cause-and-effect relationship between mankind’s activities and mean global temperatures.

Climate specialists say their models incorporate all this, and insist their predictions for continued warming will still hold true. (Here’s some data from the Guardian about why the “global warming is taking a break” theme may be off-base.)

Meteorologists at the UK’s Hadley Centre, for instance, point out that global temperatures aren’t linear, and that all data sets - including solar phenomenon and ocean temperatures - indicate that warming will soon pick up again.

But as Paul Hudson, the BBC’s environment reporter, points out, Mojib Latif, a member of the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, agrees that the Earth may, in fact, continue to cool for another 10 to 20 years. Mr. Latif says that doesn’t make him a climate change skeptic, just a scientist. Eventually, he says, “the overwhelming force of man-made global warming reasserts itself,” according to the BBC.

Obviously, climate change has global ecological and political implications. The cap-and-trade bill and new auto emissions rules in the US are direct responses to climate implications of CO2. December’s Copenhagen climate conference will try to seek renewed global commitment to CO2 reduction.

Taken together, what does it all mean?

“Climate change - no matter how benign or severe a course it takes - makes legislating during the 21st century one of the most complicated and complex tasks for elected officials in human history,” writes Morgan Josey Glover in the Greensboro, N.C., News-Record newspaper. See post here.

By Anthony Watts, Watts Up With That

It’s really rather sad that you can read about Svensmark’s climate research in an Iranian news outlet (FARS) but you won’t see any mention of it in American press, such as in the NYT. A search for Svensmark (and also cosmic rays) yields nothing. Maybe Andy Revkin just hasn’t gotten around to it yet, but if I were in his shoes, I wouldn’t enjoy being scooped by Iran. WUWT covered this story, complete with comments direct from Dr. Svensmark, nearly one month ago. See here.

Here’s the story from FARS:

TEHRAN (FNA)- New research by the National Space Institute in the Technical University of Denmark (DTU) validated 13 years of discoveries that point to a key role for cosmic rays in climate change.

Billions of tons of water droplets vanish from the atmosphere in events that reveal in detail how the Sun and the stars control our everyday clouds. DTU Researchers have traced the consequences of eruptions on the Sun that screen the Earth from some of the cosmic rays - the energetic particles raining down on our planet from exploded stars.

“The Sun makes fantastic natural experiments that allow us to test our ideas about its effects on the climate,” lead author of a report newly published in Geophysical Research Letters Prof. Henrik Svensmark said. When solar explosions interfere with the cosmic rays there is a temporary shortage of small aerosols, chemical specks in the air that normally grow until water vapor can condense on them, so seeding the liquid water droplets of low-level clouds (like you find off California over the cold California current below).

Because of the shortage, clouds over the ocean can lose as much as 7 per cent of their liquid water within seven or eight days of the cosmic-ray minimum. “A link between the Sun, cosmic rays, aerosols, and liquid-water clouds appears to exist on a global scale,” the report concludes. This research, to which Torsten Bondo and Jacob Svensmark contributed, validates 13 years of discoveries that point to a key role for cosmic rays in climate change.

In particular, it connects observable variations in the world’s cloudiness to laboratory experiments in Copenhagen showing how cosmic rays help to make the all-important aerosols. Other investigators have reported difficulty in finding significant effects of the solar eruptions on clouds, and Henrik Svensmark understands their problem.

“It’s like trying to see tigers hidden in the jungle, because clouds change a lot from day to day whatever the cosmic rays are doing,” he says.

The first task for a successful hunt was to work out when “tigers” were most likely to show themselves, by identifying the most promising instances of sudden drops in the count of cosmic rays, called Forbush decreases. Previous research in Copenhagen predicted that the effects should be most notice-able in the lowest 3000 meters of the atmosphere. The team identified 26 Forbush decreases since 1987 that caused the biggest reductions in cosmic rays at low altitudes, and set about looking for the consequences.

The first global impact of the shortage of cosmic rays is a subtle change in the color of sunlight, as seen by ground stations of the aerosol robotic network AERONET. By analyzing its records during and after the reductions in cosmic rays, the DTU team found that violet light from the Sun looked brighter than usual. A shortage of small aerosols, which normally scatter violet light as it passes through the air, was the most likely reason. The color change was greatest about five days after the minimum counts of cosmic rays.

Henrik Svensmark and his team were not surprised by it, because the immediate action of cosmic rays, seen in laboratory experiments, creates micro-clusters of sulphuric acid and water molecules that are too small to affect the AERONET observations. Only when they have spent a few days growing in size should they begin to show up, or else be noticeable by their absence. The evidence from the aftermath of the Forbush decreases, as scrutinized by the Danish team, gives aerosol experts valuable information about the formation and fate of small aerosols in the Earth’s atmosphere.

Although capable of affecting sunlight after five days, the growing aerosols would not yet be large enough to collect water droplets. The full impact on clouds only becomes evident two or three days later. It takes the form of a loss of low-altitude clouds, because of the earlier loss of small aerosols that would normally have grown into “cloud condensation nuclei” capable of seeding the clouds. “Then it’s like noticing bare patches in a field, where a farmer forgot to sow the seeds,” Svensmark explains. “Three independent sets of satellite observations all tell a similar story of clouds disappearing, about a week after the minimum of cosmic rays.”

Averaging satellite data on the liquid-water content of clouds over the oceans, for the five strongest Forbush decreases from 2001 to 2005, the DTU team found a 7 per cent decrease, as mentioned earlier. That translates into 3 billion tons of liquid water vanishing from the sky. The water remains there in vapor form, but unlike cloud droplets it does not get in the way of sunlight trying to warm the ocean. After the same five Forbush decreases, satellites measuring the extent of liquid-water clouds revealed an average reduction of 4 per cent. Other satellites showed a similar 5 per cent reduction in clouds below 3200 meters over the ocean.

“The effect of the solar explosions on the Earth’s cloudiness is huge,” Henrik Svensmark comments. “A loss of clouds of 4 or 5 per cent may not sound very much, but it briefly increases the sunlight reaching the oceans by about 2 watt per square meter, and that’s equivalent to all the global warming during the 20th Century.”

The Forbush decreases are too short-lived to have a lasting effect on the climate, but they dramatize the mechanism that works more patiently during the 11-year solar cycle. When the Sun becomes more active, the decline in low-altitude cosmic radiation is greater than that seen in most Forbush events and the loss of low cloud cover persists for long enough to warm the world. That explains, according to the DTU team, the alternations of warming and cooling seen in the lower atmosphere and in the oceans during solar cycles.

The director of the Danish National Space Institute, DTU, Eigil Friis-Christensen, was co-author with Svensmark of an early report on the effect of cosmic rays on cloud cover, back in 1996. Commenting on the latest paper he said, “The evidence has piled up, first for the link between cosmic rays and low-level clouds and then, by experiment and observation, for the mechanism involving aerosols. All these consistent scientific results illustrate that the current climate models used to predict future climate are lacking important parts of the physics”. See post here.

World Climate Report

The United Nations Environmental Programme just released a major report in advance of the Climate Change Summit to take place in Copenhagen this December. The report is intended to “show how the science has been evolving” since the publication of the IPCC’s Fourth Assessment Report in the spring of 2007.

Although we suppose we shouldn’t judge a book by its cover, we are having a lot of difficulty bringing ourselves to think that the contents provide a fair representation of the recent state climate change science.

The title says “Climate Change 2009: Science Compendium” but the cover illustration screams “Political Propaganda!” Here is the cover of the UNEP report:

What is this illustration supposed to be representing?

It shows the earth, slipping through an hourglass and coming out not as just a pile of sand, but as a desert, replete with sand dunes.

I guess the symbolism is supposed to be that time is running out on our ability to save the earth from this fate. Apparently climate change is going to turn the earth from predominantly a blue and green vibrant planet (in the top half of the hourglass) to a brown lifeless one (in the bottom of the hourglass).

Whoever dreamt up this symbolism demonstrates a remarkable failure to grasp even the most basic premise of the science and projections of climate change. While we are not graphic artists, let us suggest a more apt concept.

By adding carbon dioxide to the atmosphere as a result of burning fossil fuels to produce the energy that we all rely on to power our way of life and in doing so improve our general health and welfare, we are enhancing the earth’s greenhouse effect.

(Note to UNEP art department: when you think of the contents of a greenhouse, you don’t think of a desert.)

Our enhancement of the greenhouse effect is expected, on a global average, to lead to higher temperatures (like inside a greenhouse), higher humidity (like inside a greenhouse), more precipitation (like inside a greenhouse), longer growing seasons (like inside a greenhouse), and enhance the fertilization effect of airborne carbon dioxide (just like commercial greenhouses which pump CO2 inside them to increase plant growth and productivity). Taken together, this brings up images of lush tropical foliage, not a dry, lifeless, desert.

Our guess is, a lush green world this isn’t the image that they wanted to conjure up about climate change and UNEP’s art department couldn’t come up with a way to make this seem bad (hint: next time, check with Al Gore).

If the UNEP wanted to advertise right from the get go that its report was filled with nonsense, the selection of its cover illustration made that loud and clear.

Although we have thus far not been able to bring ourselves to look past the cover to see what lurks inside, others apparently have, and what they have reported back is that the contents are as scientifically soft as the cover. See post here.