Scientists are human and have their opinions. Although we may like to think of science as a purely objective search after truth, we have to be realistic. It would be all but impossible for a researcher to start an experiment without having some idea about the expected outcome. Objectivity then comes in the form of a willingness to accept evidence which points to a different answer. Nevertheless, in most cases there is likely to be a tendency towards confirmation bias: giving more weight to observations which conform to your expectations or opinions.

A well-known example of this is the determination of the charge on an electron, famously first measured in the Millikan oil-drop experiment just over a hundred years ago. This balanced the gravitational pull on tiny oil drops by an applied electric field. Millikan arrived at a value (to five significant figures) which was very close to the accepted present-day value, but it turned out he had the wrong value for one of the factors in the equation. The ever-insightful and quotable Richard Feynman spoke about this in his 1974 commencement address at Caltech (’cargo cult science’![]() :

:

“...Millikan measured the charge on an electron by an experiment with falling oil drops, and got an answer which we now know not to be quite right. It’s a little bit off because he had the incorrect value for the viscosity of air. It’s interesting to look at the history of measurements of the charge of an electron, after Millikan. If you plot them as a function of time, you find that one is a little bit bigger than Millikan’s, and the next one’s a little bit bigger than that, and the next one’s a little bit bigger than that, until finally they settle down to a number which is higher.

Why didn’t they discover the new number was higher right away? It’s a thing that scientists are ashamed of - this history - because it’s apparent that people did things like this: When they got a number that was too high above Millikan’s, they thought something must be wrong- and they would look for and find a reason why something might be wrong. When they got a number close to Millikan’s value they didn’t look so hard. And so they eliminated the numbers that were too far off...”.

That is one form of human behaviour we can probably do little about. But there comes a point beyond which science itself is misused and compromised. Rather than having evidence-based policymaking, we end up with policy-based evidence picking. A good (or, should I say, bad) example appeared in the Times this week. The headline says it all: Scientists accused of plotting to get pesticides banned.

The fuss is over the (currently temporary) EU ban on neonicotinoid insecticides over allegations that they are at least partly to blame for recent declines in the population of bees. Environmentalist groups had been campaigning against this class of compounds for many years, despite little evidence of any connection under real life conditions. What tipped the balance was a report from the Task Force on Systemic Pesticides, an advisory group to the International Union for Conservation of Nature, which reported on recent scientific work and called on regulators to “start planning for a global phase-out” of these insecticides.

However, the chairman of the Task Force, Maarten Bijleveld van Lexmond, and chairman of the IUCN, Piet Wit, were both at a meeting in Switzerland in June 2010 at which, according to a note leaked to the Times “...scientists agreed to select authors to produce four papers and co-ordinate their publication to ‘obtain the necessary policy change, to have these pesticides banned’. A paper by a ‘carefully selected first author’ would set out the impact of the pesticides on insects and birds ‘as convincingly as possible’. A second ‘policy forum’ paper would draw on the first to call for a ban..."If we are successful in getting these two papers published, there will be enormous impact, and a campaign led by WWF etc. It will be much harder for politicians to ignore a research paper and a policy forum paper in [a major scientific journal].’”

This smacks of environmental activism rather than objective science, despite the protestations of the Task Force chairman, “...a founding member of WWF in the Netherlands, that the Task Force was independent and unbiased.”

It seems that only scientists outside government and industry are to be regarded as independent. Self-selected bodies such as WWF are inevitably groups of like-minded people and seemingly intolerant of any dissent. Contrast this particular case, in which ‘independent’ activist scientists protest their innocence (and attract little public criticism, unfortunately) with the campaign against the European Commission’s soon-to-be ex-chief scientist, Professor Anne Glover (Chief scientist is forced out after green campaign).

Professor Glover was found guilty of holding the ‘wrong’ opinions about GM crops. The same Stalinist intolerance has also been used to keep the management board of the European Food Safety Authority free of anyone who did not conform to the ‘independent’ template. Professional scientists should be prepared to listen to conflicting views, if based on hard evidence, and not simply suppress them.

In a different area, we are now being told that World on course for warmest year, with plenty of talk of supposed increases in the incidence of extreme weather. Now, it may turn out that average temperatures in 2014 will be fractionally up on the previous high, but it is equally true to say that there has been no trend in either direction since 1998. The latest stories, put out to coincide with the current climate change talks in Lima (COP20), are designed to put pressure on negotiators to make progress towards a binding international agreement on emissions reduction at the pivotal Paris conference in a year’s time. The selection of one of the statements about temperature over the other is a clear form of confirmation bias.

While we expect scientists to be human, we should also expect them to remain grounded in scientific principles and be prepared to question their beliefs if the evidence contradicts them. To do otherwise is to compromise the integrity of the scientific community, the very characteristic which makes scientists among the most trusted groups in society.

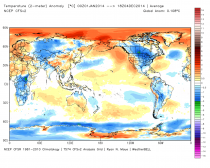

Note here is the actual year to data anomalies based oon the 4 times a day initialization that goes into the forecast models. No adjustments like homogenization are made. Does that look like the warmest year ever to you. Note the 90N and 90S is actually a point but is stretched in this projection to the same distance as the circumference at the equator. In other words it exaggerates the areal coverage of any high latitude warmth. Note the global mean compared to the 1979 to 2010 climatology is just +1.08C.

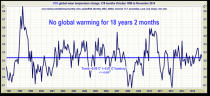

Sateliites show it is not a record year - see and see here Lord Monckton’s update showing using RSS satellite date that the pause has reached 18 years 2 months.