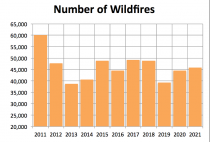

In the U.S., wildfires are in the news almost every late summer and fall. The National Interagency Fire Center (NIFC) has recorded the number of fires and acreage affected since 1985. The data shows that the trend in the number of fires was actually down while the trend in the acreage burned has increased. Longer term both number and acreage burned are down.

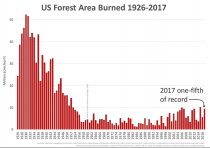

Professor Bjorn Lomborg used NIFC data with documented “Historical Statistical” fire data to show the long-term trend. He notes recent forest fire activity is one-fifth the record since 1926 even with the recent increases in acreage burnt.

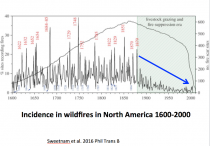

In agreement with Lomborg, Sweetnam looked at long-term incidence of wildfires in North America and found they have declined the last century though with a small rebound in recent years.

Enlarged

Natural seasonal weather variations create conditions that are conducive to seasonal fires and the rapid spread of these fires west to increasingly populated areas. Today most are the result of power lines igniting trees. The power lines have increased proportionately with the population, so it can be reasoned that most of the damage from large wildfires in California is partially a result of increased population.

The increased danger is also greatly aggravated by poor government forest management choices. ”In the United States, wildfires are also due in part to a failure to thin forests or remove dead and diseased trees”. In 2014, forestry professor David B. South of Auburn University testified to the U.S. Senate Environment and Public Works Committee that “data suggest that extremely large megafires were four-times more common before 1940,” adding that “we cannot reasonably say that anthropogenic global warming causes extremely large wildfires.” As he explained, “To attribute this human-caused increase in fire risk to carbon dioxide emissions is simply unscientific.”

ROLE OF DEVELOPMENT AND GOVERNMENT POLICIES

California’s catastrophic wildfires illuminated the years’ long stalemate between those who want to cut back the overgrown, beetle-infested national forests and environmentalists who have axed efforts to fell more trees, blaming the destructive fires on climate change. See more in the Washington Times.

In December, 2017, the U.S. Forest Service announced that California had set a record with 129 million dead trees on 8.9 million acres, the result of a five-year drought and beetle-kill, but that its tree mortality task force had removed only about 1 million.

Meanwhile, the logging industry has continued its free fall, with timber harvesting dropping by 80 percent in the past 40 years, as projects in the national forests are killed or delayed by ”frivolous litigation from radical environmentalists who would rather see forests and communities burn than see a logger in the woods,” according to our prior Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke. When a bi-partisan bill was passed in 2017 in California to help fund PGE tree cutting near power lines to lessen fire danger, it was vetoed by Governor Brown.

The LA Times in October, 2017 reported The explosive failure of power lines and other electrical equipment has regularly ranked among the top three singular sources of California wildfires for the last several years. In 2015, the last year of reported data, electrical power problems sparked the burning of 149,241 acres - more than twice the amount from any other cause.

Tree cuttings near power lines, burying the power lines where possible would help though it would not prevent fires from careless campers or arsonists. Smokey Bear PSAs need to be revived.

These same radical environmentalists hold growers, farmers and ranchers in the same level of contempt they have for foresters. Their actions have led to the diversion of water to rivers and the Pacific Ocean, threatening agriculture in the #1 agricultural state for produce.

University of Washington Professor of Atmospheric Sciences Cliff Mass pointed out in a recent interview with the Daily Caller: “Wildfire area could well be increasing because of previous fire suppression, mismanagement of our forests, and a huge influx of people into the west, lightning fires and providing lots of fuel for them.”

University of Alabama-Huntsville’s Distinguished Professor of Atmospheric Science John Christy says human mismanagement is the more important cause of the huge fires: “If you don’t let the low-intensity fires burn, that fuel builds up year after year. Now once a fire gets going and it gets going enough, it has so much fuel that we can’t put it out. In that sense, you could say that fires today are more intense, but it’s because of human management practices, not because mother-nature has done something.”

In this Wall Street Journal opinion piece Only Good Management Can Prevent Forest Fires , Tom McClintock writes:

“There’s nothing new about catastrophic blazes. It’s how nature has always dealt with overgrowth.”

“Excess timber comes out of a forest in two ways - it gets carried out or burned out. For much of the 20th century, harvesting excess timber produced thriving forests by matching tree density to the ability of the land to support it. Foresters designated surplus trees, and loggers bid for the right to remove them at auction, with the proceeds going to the U.S. Treasury. These revenues were then put back into forest management and shared with local communities.

What went wrong? In the 1970s, Congress passed a series of laws subjecting federal land management to time-consuming and cost-prohibitive environmental regulations. Instead of generating revenues, forest management now costs the government money. As a result, timber harvested from federal lands has declined 80%, while acreage destroyed by fire has increased proportionally.”

Sen. Feinstein blames Sierra Club for blocking wildfire bill” reads the provocative headline on a 2002 story in California’s Napa Valley Register. Feinstein had brokered a congressional consensus on legislation to thin ‘overstocked’ forests close to homes and communities, but could not overcome the environmental lobby’s disagreement over expediting the permit process to thin forests everywhere else.

Fire suppression along with too many environmentalist-inspired bureaucratic barriers to controlled burns and undergrowth removal turned the hillsides and canyons of Southern California into tinderboxes.

Climate change spares private forests:

Katy Grimes, editor of the California Globe suggests the large wildfires relate to a lack of proper forest management in government-run forests:

“For decades, traditional forest management was scientific and successful, until ideological, preservationist zealots wormed their way into government and began the 40-year overhaul of sound federal forest management through abuse of the Endangered Species Act and the no-use movement...”

The same climate change impacts private lands as public lands, but private forests are not burning down because they are properly managed. Or if a fire does break out on privately managed forest land, it is often extinguished more quickly and easily because the trees aren’t so close together and the underbrush has been cleared away.

2021

NIFC Report 09/26/21 “After a very dry winter Nationally, 64 large fires have burned over 3,140,000 acres...The biggest fire in California, the so-called Dixie fire became the largest fire in the state’s history.”

The droughty winter and spring prevented the explosive growth of vegetation we see after wet winters and springs which dries in the summer heat to become additional fuel for fires. This helped to hold down the number of fires and total acreage burned.

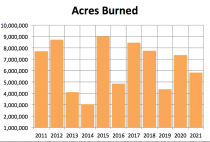

See since 2009 that there is a downward trend for number of fires and no clear trend for acres burned.

Enlarged

2022 FIRE SEASON OUTLOOK

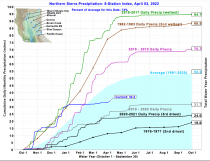

A two-year La Nina continues. We managed a wet October and December, but as the La Nina pulsed stronger, the rains shutoff. Still we are running above last year’s Water Year (October to September), which ranked in the top 3 driest.

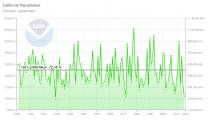

1923/34 and 1976/77 were drier than 2021/22. The trend since 1895 for California is flat, in contrast with the tinker-toy million dollar climate models.

With chances for rains diminishing this spring and during the normal hot, dry western summer, fires will be in the news. Natural factors, population growth and continued governmental and environmental mismanagement ensure that.

By the way, they are also hyping flash flooding and mudslides increasing. we agree, on slopes where major fires have removed vegetation, heavy rains from thunderstorms will cause mudslides.

Bottom Line

In summary, alternating wet and dry years and impacts of annual end of dry season forest fires are a population growth, forest management and environmental and governmental policy induced issue, not a “Global Warming” one.