Nov 25, 2009

Extreme Heat vs. Extreme Cold: Which is the Greatest Killer?

By Sherwood, Keith and Craig Idso

Hypocrisy in high places is nothing new; but the extent to which it pervades the Climategate Culture - which gave us the hockeystick history of 20th-century global warming - knows no bounds.

Hard on the heels of recent revelations of the behind-the-scenes machinations that led to the IPCC’s contending that the current level of earth’s warmth is the most extreme of the past millennium, we are being told by Associated Press “science” writer Seth Borenstein (25 November 2009) that “slashing carbon dioxide emissions could save millions of lives.” And in doing so, he quotes U.S. Health and Human Services Secretary Kathleen Sebelius as saying that “relying on fossil fuels leads to unhealthy lifestyles, increasing our chances for getting sick and in some cases takes years from our lives.”

Well, if you’re talking about “cook stoves that burn dung, charcoal and other polluting fuels in the developing world,” as Seth Borenstein reports others are doing in producing their prognoses for the future, you’re probably right. But that has absolutely nothing to do with the proper usage of coal, gas and oil. In fact, any warming that might result from the burning of those fuels would likely lead to a significant lengthening of human life.

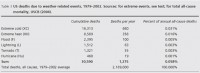

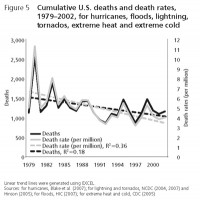

In an impressive study recently published in The Review of Economics and Statistics, for example, Deschenes and Moretti (2009) analyze the relationship between weather and mortality, based on “data that include the universe of deaths in the United States over the period 1972-1988,” wherein they “match each death to weather conditions on the day of death and in the county of occurrence,” which “high-frequency data and the fine geographical detail,” as they write, allow them “to estimate with precision the effect of cold and hot temperature shocks on mortality, as well as the dynamics of such effects,” most notably, the existence or non-existence of a “harvesting effect,” whereby the temperature-induced deaths either are or are not subsequently followed by a drop in the normal death rate, which could either fully or partially compensate for the prior extreme temperature-induced deaths.

So what did they find?

The two researchers say their results “point to widely different impacts of cold and hot temperatures on mortality.” In the later case, they discovered that “hot temperature shocks are indeed associated with a large and immediate spike in mortality in the days of the heat wave,” but that “almost all of this excess mortality is explained by near-term displacement,” so that “in the weeks that follow a heat wave, we find a marked decline in mortality hazard, which completely offsets the increase during the days of the heat wave,” such that “there is virtually no lasting impact of heat waves on mortality [italics added].”

In the case of cold temperature days, they also found “an immediate spike in mortality in the days of the cold wave,” but they report that “there is no offsetting decline in the weeks that follow,” so that “the cumulative effect of one day of extreme cold temperature during a thirty-day window is an increase in daily mortality by as much as 10% [italics added].” In addition, they say that “this impact of cold weather on mortality is significantly larger for females than for males,” but that “for both genders, the effect is mostly attributable to increased mortality due to cardiovascular and respiratory diseases.”

In further discussing their findings, Deschenes and Moretti state that “the aggregate magnitude of the impact of extreme cold on mortality in the United States is large,” noting that it “roughly corresponds to 0.8% of average annual deaths in the United States during the sample period.” And they estimate that “the average person who died because of cold temperature exposure lost in excess of ten years of potential life [italics added],” whereas the average person who died because of hot temperature exposure likely lost no more than a few days or weeks of life. Hence, it is clear that climate-alarmist concerns about temperature-related deaths are wildly misplaced, and that halting global warming - if it could ever be done - would lead to more thermal-related deaths, because continued warming, which is predicted to be greatest in earth’s coldest regions, would lead to fewer such fatalities.

Interestingly, the two scientists report that many people in the United States have actually taken advantage of these evident facts by moving “from cold northeastern states to warm southwestern states.” Based on their findings, for example, they calculate that “each year 4,600 deaths are delayed by the changing exposure to cold temperature due to mobility,” and that “3% to 7% of the gains in longevity experienced by the U.S. population over the past three decades are due to the secular movement toward warmer states in the West and the South, away from the colder states in the North.”

It’s really a no-brainer. An episode of extreme cold can shave an entire decade off one’s life, while an episode of extreme warmth typically hastens death by no more than a few weeks. If you love life, therefore, you may want to reconsider the so-called “morality” of the world’s climate-alarmist’s perverse prescription for planetary health.

For more information on this important subject, we suggest that you see the most recent publication (Climate Change Reconsidered) of the Nongovernmental International Panel on Climate Change. If Borenstein were a real science writer, he would check out the findings of the voluminous body of peer-reviewed scientific literature on this and many other related subjects that is reported there. To simply ignore the other side of the issue, especially in a “news” story, must surely come close to bordering on fraud. But we guess that must be the defining characteristic of the Climategate Culture.

Reference: Deschenes, O. and Moretti, E. 2009. Extreme weather events, mortality, and migration. The Review of Economics and Statistics 91:659-681.

Read more here.

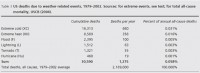

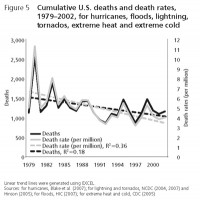

See agreement in “The Deadliest US Hazard - Extreme Cold” by Indur Glokany here.

Enlarged Table of Deaths by Hazard, Glokany 2008 here.

Enlarged Death Trend image here.

Nov 25, 2009

Prince Charles Tries to Stamp Out Scientific Debate; Climate Science Corrupted by the IPCC

SPPI

A climate lobby-group founded by Prince Charles to influence opinion in the world’s largest insurance market has tried - and failed - to stifle scientific debate on “global warming” in one of the industry’s foremost academic journals, says SPPI.

ClimateWise, known to skeptical brokers at Lloyds of London as Climate Foolish, was launched by the Prince of Wales in 2007 with the words, “Time is a luxury we do not have and I urge companies both at home and internationally to sign the ClimateWise principles and take the necessary action.”

The ClimateWise principles are “To lead in risk analysis, inform public policymaking, support climate awareness amongst customers, incorporate climate change into investment strategies, reduce businesses’ environmental impact, report and be accountable”.

SPPI’s Lord Monckton and a leading insurance broker, Paul Maynard, jointly wrote a learned paper for the respected Journal of the Chartered Insurance Institute, reviewing the science in detail and concluding that the climate scare is bogus and scientifically unfounded; and that CO2 is harmless and beneficial.

Before the paper was published in the Journal, members of ClimateWise first of all attempted to prevent it from appearing. Then they tried to censor it by removing the central scientific and mathematical argument that the effect of CO2 on temperature is now known to be around one-third to one-seventh of what the UN - and the Prince of Wales - would like us to believe. The co-authors stood firm, however, and successfully insisted that their article be printed in full as originally agreed. Next, ClimateWise supporters successfully lobbied the Journal not to reveal to its readers that the letters to the Editor about the paper had been overwhelming supportive of it.

Lord Monckton expressed concern to ClimateWise about “the engagement of the Prince of Wales in a lobby-group with an avowedly political purpose when the future Monarch is constitutionally constrained to be above politics.” The pressure-group has not responded.

SPPI is pleased to announce the publication of a major original paper by Lord Monckton. “Global warming” - a Debate at Last tells the gripping story of the attempted censorship on the part of the Prince of Wales’ pressure-group, reproduces the Journal climate paper in full, and also reveals an attempt by an IPCC scientist associated with ClimateWise to write a lengthy rebuttal of the paper.

ClimateWise supporters tried to persuade the Journal to publish a letter from the scientist and provide a weblink to the rebuttal without allowing the authors the right of reply. Upon threatened suit for equal standing for Lord Monckton, the Journal decided not to publish either the rebuttal or Lord Monckton’s response. SPPI’s paper reproduces not only the original article but also the IPCC scientist’s rebuttal and Lord Monckton’s response, in full.

Robert Ferguson, SPPI’s president, said: “Historians of the future, trying to answer the question why the world’s political and business elites so credulously fell for the ‘global warming’ scare, may well recognize this paper as significant and revealing. It describes the serial attempts at censorship and suppression of legitimate academic and scientific debate that surrounded the publication of Monckton-Maynard paper in the Journal of the CII.

“Better still,” continued Ferguson, “this paper is a rare instance of a real scientific debate about the climate. Normally climate catastrophists do not allow themselves to be drawn into debate, usually reciting the wilted mantra that ‘the science is settled and the debate is over.’ This time Dr. Dlugolecki, an IPCC contributor himself, after considerable assistance from what he described in an email to the Journal as ‘top scientists’, has actually debated the science. Monckton’s responses to the IPCC scientist’s argument, paragraph by relentless paragraph, should be appreciated by any serious seeker of understanding.

Says Monckton, “Perhaps Prince Charles would do better finding a new, less political, and more scientifically-credible subject for his campaigning zeal.”

Monckton added, “The Prince, whom we all love dearly, should resign from Climate Foolish for his own benefit.”

The paper can be read here.

Climate Science Corrupted by the IPCC

See also the SPPI Climate Science Corrupted by the IPCC by John McLean.

SUMMARY FOR POLICY MAKERS

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) was established under the sponsorship of the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). The UNEP’s belief in manmade warming in the late 1970’s led to a stage-managed conference in Villach in

1985, which in turn led to the political decision to form the IPCC.

The IPCC rose to prominence because people with clear bias were appointed to key positions where they could influence the development of the entire organization. Bert Bolin, the first chairman of the IPCC was already heavily committed to the notion of manmade warming having worked previously for the UNEP, WMO, the Brundtland Report, the SCOPE 29 report (on which the first IPCC report was largely based) and, very crucially, having documented that the Villach conference reached a consensus that manmade emissions of carbon dioxide were to blame for variations in climate. John Houghton, the first

chairman of the IPCC working group that attributes blame for climate change, was assisted in his assertions by his staff at the UK Met Office and by a

very supportive UK government.

The other key factor for the IPCC was the adoption of the UNEP’s methods of coercing governments and the general public. Those methods included (a) the

use of the environmentalists’ catch-all the “precautionary principle”, (b) a penchant for creating models based on partially complete scientific understanding and then citing the output of those models as evidence, (c) the politicisation of science through the implied claim that consensus determines scientific truth, (d) the use of strong personalities and people of influence, and (e) the manipulation of the media and public opinion.

Directly and indirectly these methods greatly influenced political parties whether they held government or not. None of these UNEP techniques provide scientific justification of the IPCC’s principal claim, which considered dispassionately, is very weak. Not only is it based on the output of climate models, that the IPCC shows us are built according to incomplete knowledge and therefore cannot be accurate, but also on the opinions of those who use such models as if somehow the models were credible and scientific truth should be determined by consensus and opinion.

It is long overdue that the IPCC was called for what it is - a political body driven not by the evidence that it pretends exists but by the beliefs and philosophies of the UNEP, the IPCC’s sponsor, and by the initial holders of key IPCC positions.

Again see this must read the very detailed analysis Climate Science Corrupted by the IPCC. See also this Roger Pielke Sr. post on his Climate Science weblog on the IPCC WG1 analysis.

Nov 25, 2009

ClimateGate: An Opportunity to Stop and Think

By Joseph Bast

Last week, someone (probably a whistle-blower at the Climate Research Unit at the University of East Anglia, England) released emails and other documents written by Phil Jones, Michael Mann, and other leading scientists who edit and control the content of the reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). The emails appear to show a conspiracy to falsify data and suppress academic debate in order to exaggerate the possible threat of man-made global warming.

The misconduct exposed by the emails is so apparent that one scientist, Tim Ball, said it marked “the death blow to climate science.” Another, Patrick Michaels, told The New York Times, “This is not a smoking gun; this is a mushroom cloud.”

Although I am not a scientist, I know something about global warming, having written about the subject since 1993 and recently edited an 800-page comprehensive survey of the science and economics of global warming, titled Climate Change Reconsidered, written by a team of nearly 40 scientists for the Nongovernmental International Panel on Climate Change (NIPCC).

The content of the emails doesn’t surprise me and other “skeptics” in the global warming debate. We have been saying for many years that the leading alarmists have engaged in academic fraud, do not speak for the larger scientific community, and are exaggerating the scientific certainty of their claims. Tens of thousands of scientists share our views, including many whose credentials are far superior to those of the dozen or so alarmists the media choose to quote and promote.

The implications of these emails are enormous: They mean the IPCC is not a reliable source of science on global warming. And since the global movement to “do something” about global warming rests almost entirely on the IPCC’s claim to represent the “consensus” of climate science, that entire movement stands discredited.

The release of these documents creates an opportunity for reporters, academics, politicians, and others who relied on the IPCC to form their opinions about global warming to stop and reconsider their position. The experts they trusted and quoted in the past have been caught red-handed plotting to conceal data, hide temperature trends that contradict their predictions, and keep critics from appearing in peer-reviewed journals. This is new and real evidence that they should examine and then comment on publicly.

It is possible that the emails and other documents aren’t as damning as they appear to be on first look. (I’ve read about two dozen of them myself and find them appalling, but others may not.) Looking at how past disclosures of fraud in the global warming debate have been dismissed or ignored by the mainstream media leads me to suspect they will try to sweep this, too, under the rug. But thanks to the Internet, millions of people will be able to read the emails themselves and make up their own minds. This incident, then, will not be forgotten. The journalists who attempt to spin it away and the politicians who try to ignore it will further damage their own credibility, and perhaps see their careers shortened as a consequence.

Recent polls show only a third of Americans believe global warming is the result of human activity, and even fewer think it is a major environmental problem. This new scandal, combined with a huge body of science and economics ignored or deliberately concealed by the alarmists, proves that the large majority of Americans was right all along.

How did the Average Joe, who knows so little about the real science of climate change, figure out that global warming is not a crisis when so many journalists were completely taken in by it? I think he saw some clues early on that most journalists, because of their liberal biases, missed.

Average Joe noticed how Al Gore and other Democratic politicians were quick to capitalize on the matter, even before the scientific community could speak with a unified voice on the issue. He figured out, correctly, that politics rather than science was the force that put global warming on the front pages of the newspapers and on television every night.

He also probably noticed that spokespersons for liberal advocacy groups like Greenpeace and the Union of Concerned Scientists were suddenly being quoted in the press as experts on climate change, whereas just a few years earlier they were (rightly) considered radical fringe groups. Fenton Communications fooled the mainstream media, but not the rest of us.

And Average Joe noticed how global warming “skeptics,” even distinguished scientists and trusted people like former astronauts, were ignored, rejected, or demonized by the press just for asking for proof, and for not going along with the latest and increasingly silly claims about all the things global warming was supposedly causing: droughts and floods, warming and cooling, “global warming refugees,” and so on.

While the issue of global warming is complex, one need not be a genius to figure out that man’s role is small, that the effects of modest warming of the kind seen in the latter half of the twentieth century were at least as positive as negative, and that scientists who can’t predict next week’s weather probably can’t predict what climate conditions will be like one hundred years from now. This isn’t “denial,” it’s just common sense. The executive summary of Climate Change Reconsidered makes these points and more, in plain English, and it is only eight pages long. The report itself contains more than 4,000 citations to peer-reviewed literature.

The IPCC email scandal makes this a good time for reporters and other opinion leaders to take a serious look at the skeptics’ case in the global warming debate and perhaps move to the middle, where serious journalists and honest elected officials should have been all along. A good place to start is The Heartland Institute’s Web site devoted to global warming realism.

It’s not too late to regain some of the native skepticism that Average Joe relied on all along to see through the global warming scam.

Joseph Bast is president of The Heartland Institute and editor of Climate Change Reconsidered: The 2009 Report of the Nongovernmental International Panel on Climate Change, by Dr. Craig Idso and Dr. S. Fred Singer (Chicago, IL: The Heartland Institute, 2009). The book’s executive summary and contents can be downloaded for free from www.nipccreport.org.

Nov 24, 2009

A Critique of the October 2009 NCAR Study Regarding Record Maximum to Minimum Ratios

By Bruce Hall, Hall of Records

The NCAR [National Center for Atmospheric Research] study titled “The relative increase of record high maximum temperatures compared to record low minimum temperatures in the U.S.” was published October 19, 2009.”

Abstract

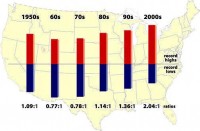

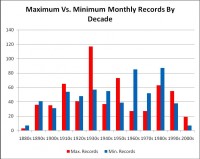

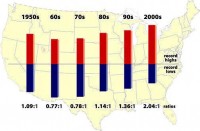

The current observed value of the ratio of daily record high maximum temperatures to record low minimum temperatures averaged across the U.S. is about two to one. This is because records that were declining uniformly earlier in the 20th century following a decay proportional to 1/n (n being the number of years since the beginning of record keeping) have been declining less slowly for record highs than record lows since the late 1970s. Model simulations of U.S. 20th century climate show a greater ratio of about four to one due to more uniform warming across the U.S. than in observations. Following an A1B emission scenario for the 21st century, the U.S. ratio of record high maximum to record low minimum temperatures is projected to continue to increase, with ratios of about 20 to 1 by mid-century, and roughly 50 to 1 by the end of the century.” The following is a graphic representation of the study from the UCAR website (below, enlarged here):

“This graphic shows the ratio of record daily highs to record daily lows observed at about 1,800 weather stations in the 48 contiguous United States from January 1950 through September 2009. Each bar shows the proportion of record highs (red) to record lows (blue)for each decade. The 1960s and 1970s saw slightly more record daily lows than highs, but in the last 30 years record highs have increasingly predominated, with the ratio now about two-to-one for the 48 states as a whole.”

While this study does use sound methodology regarding the data it has included, it falls short of being both statistically and scientifically complete. Hence, the conclusions from this study are prone to significant bias and any projections from this study are likely incorrect.

Comments

The NCAR Study contains at least two biases:

The selection of 1950 through 2006 significantly biases the outcome of this study because the U.S. was entering a cooling period in the 1960s and 1970s which creates the illusion of unusual subsequent warming from 1980 through 2006. During the last decade, a large reduction of rural reporting stations in the U.S. has biased records toward urbanized and urbanizing areas. Land use changes as well as deterioration of urban siting versus NOAA standards [here] have resulted in a bias toward over-reporting/erroneous reporting of high temperature records and an under-reporting of low temperature records.

The charts in the Surface Stations study nearly 4/5ths of the U.S. weather stations and demonstrate a significant bias toward errors greater than +2C or about three times the total trend reported for global warming.

Comparison of Statewide Monthly Temperature Records with the NCAR Study

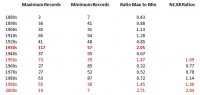

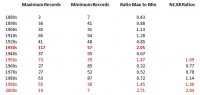

Let us look at the statewide monthly maximum and minimum records by decade beginning in 1880. Those records are used to calculate a ratio of maximum and minimum records by decade and then compared with the NCAR study ratios (below, enlarged here).

There are two aspects of this comparison that jump out to the reader:

The 1930s were, by far, the hottest period for the time frame. The ratio of maximum to minimum temperatures is greater in the 2000s, but the absolute number of monthly statewide extreme records is far less significant making the ratio far less significant.

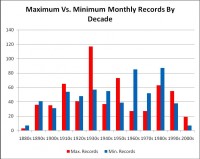

The general pattern of ratios for the monthly records follows reasonably closely to the pattern of the daily individual location records, on a decadal basis. Now let us take the two data sets and plot the ratios and see what conclusions we might draw remembering that in absolute terms, the 1930 had a much higher frequency of maximum temperature extremes than the 1990s or 2000s or the combination of the last two decades (below, enlarged here).

Keep in mind that there are significant biases toward recording daily warmer temperatures due to the closure of thousands of rural stations and expansion of urban areas into previously rural or suburban areas, creating enormous “heat sinks,” that prevent night time temperatures from dropping to the extent that they would in a nearby rural setting. Hence more stations reporting greater frequencies of maximum temperatures and fewer minimums.

Conclusion

The oscillating or cyclical nature of our climate is completely overlooked when one takes a small time frame such as the 1950s through 2006 and extrapolates a full century beyond. Even 130 years of data, starting from a relatively cold period, gives a very brief look at climate history for the U.S. and certainly one that is not sufficient to extrapolate a general warming trend, much less an accelerating one.

In the face of the recent decline in new all-time monthly statewide maximum records, it is more probably that we may be facing a cyclical decline in our overall temperature and that something similar to the 1960s and 1970s may be a far more realistic projection. Our most recent winters have been particularly colder than long-term averages and minimal sunspot activity may be another harbinger of this normal cyclical variation in our relatively stable climate.

For more information about this and related topics, please check out the following blogs: Climate Science, Icecap, Watts Up With That? The authors have contributed ideas and advice for this post. See much more detail in the full post here. See also Roger Pielke Sr.’s post on the NCAR study here.

Icecap Note: Thanks Bruce for this detailed analysis. The NCAR study is another example of a cherry picking study with a period of study beginning near the start of the PDO cold period that started in 1947 and carried through the warm PDO. The current decade of state data is showing fewer records not an acceleration. See comments by Roger Pielke Sr. early this upcoming week here and Anthony Watts here and World Climate Report new here.

Dr. Richard Keen, University of Colorado has added “My book, Skywatch West, covers the weather and climate of the 11 western states, plus Alaska, plus 6 western Canadian provinces and territories. The chapter on temperature extremes includes a chart of the occurrences (by decade) of the all-time extreme temperatures for each of the 18 states, provinces, and territories (a total of 36 records in all) (below, enlarged here). Some fun statistics from this are: of the all-time record maximum temperatures, 10 occurred before 1940 (the first six decades), and 8 after (the second six decades). For record minimum temperatures, the reverse is true: 8 records before 1940, 10 afterwards. Half of the records - 8 maximum and 10 minimum, a total of 18 - occurred during the middle three decades of the 1930’s, 40’s, and 50’s, and of these nearly a third of the total (10) were during the 1930’s alone. No records occurred in the 2000’s up to the publication date of the book (2004). Since then Arizona’s record maximum was tied, but not broken, in 2007.” (below, enlarged here)

UPDATE: See Bruce’s follow-up study with projections of the observed cyclical trends here.

Nov 24, 2009

All Pain, No Gain

By Paul Driessen

Restricting and taxing energy use to prevent speculative climate disasters would be disastrous. “Electricity rates would necessarily skyrocket” under cap-and-trade,” President Obama has admitted. “Industry will have to retrofit its operations. That will cost money, and they will pass that cost on to consumers.” Cap-and-trade, Senator Ben Cardin (D-MD) eagerly observed, is “the most significant revenue-generating proposal of our time.”

Not one congressman even read the numbingly complex 1427-page Waxman-Markey global warming bill, before the House of Representatives voted on it. A new version of the Kerry-Boxer Senate bill provides no details about how carbon allowances would be allocated under a mandatory emissions reduction program.

The process recalls Churchill’s description of Russia: “a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.” Here we are dealing with estimates wrapped in assumptions inside speculation - based on assertions that Earth faces a manmade climate disaster.

The only thing known with certainty is that cap-tax-and-trade will inflict intense pain for no environmental gain - on regions, states, communities, industries, companies and families. It is a complicated regulatory scheme that penalizes businesses and people who use electricity and other forms of energy derived from oil, gasoline, natural gas and coal.

Cap-tax-and-trade would place limits on how much carbon dioxide America would be allowed to generate, and the limits would decrease drastically over time. Companies and utilities would be issued permits, saying how much CO2 they can put into the air each year. If they cannot stay within that limit, they will have to switch to wind, solar, nuclear or geothermal energy (assuming those sources can be built, in the face of regulation and litigation); capture the CO2 and store it somewhere (via technologies that do not yet exist); or buy more permits from US or foreign companies that don’t need as much energy (through a new international financial, trading and carbon derivatives market).

Cap-and-trade restricts and taxes hydrocarbon energy use. Because 85% of America’s energy is hydrocarbons, prices will soar for everything we heat, cool, drive, make, grow, eat and do. The impacts will be especially painful in scores of states that depend on coal for 50-98% of their electricity, refine petroleum for the nation’s vehicles, and manufacture products that improve, enhance and safeguard our lives.

The complex system will be administered by profit-seeking carbon management and trading firms, regulated and policed by thousands of government bureaucrats, and paid by every family, driver, business, school district, hospital, airline, traveler and farmer.

The ostensible goal is to stabilize planetary temperatures, climates and weather patterns that have never been stable, by slashing carbon dioxide emissions 83% below 2005 levels by 2050.

The last time America emitted that amount of CO2 was 1908! Once we account for the far lower population, manufacturing, transportation and electrification levels of a century ago, 2050 carbon dioxide emissions would have to equal what the United States emitted after the Civil War!

That would require monumental changes in lifestyles and living standards. It would mean politicians and unelected pressure groups, bureaucrats and judges will limit or dictate home building, heating, cooling and lighting decisions; transportation and vacation choices; how food can be grown and shipped; what kinds of products can be purchased and how they must be manufactured; and how much energy must come from subsidized, unreliable renewable sources.

Restrictions and taxes on fossil fuels will hit our manufacturing heartland especially hard, as it is heavily dependent on coal and natural gas. The American Council for Capital Formation calculated that Waxman-Markey would spike Indiana’s electricity prices nearly 60% by 2030 - increasing school and hospital energy costs 28-42% and causing numerous jobs to be exported to Asia, where there will be few restrictions on CO2 emissions. Numerous other states would be similarly hard hit, says ACCF.

Other experts have calculated that cap-and-trade would destroy millions of American jobs, raise energy costs for the average US family by $1,400 to $3,100 per year and send overall food and living costs upward by $4,600 annually. Will you be able to afford that?

Poor families may get energy welfare. Wealthier families can absorb these costs. But cap-and-trade will severely affect middle class families. They would be forced to pay skyrocketing energy and food costs, by cutting their college, retirement and vacation budgets. Hospitals and school districts would have to raise fees and taxes, or cut services. Cities and states would have to cover rising welfare and unemployment costs, as tax revenues dwindle. Tourism-based businesses and economies would get hammered.

Switching to renewable energy does not merely increase costs and reduce reliability. It also affects the environment. Ethanol mandates would mean growing corn or switchgrass on farmland the size of Montana, and using vast amounts of water, fertilizer, diesel fuel, natural gas and insecticides.

Wind and solar power would mean covering millions of acres of scenic, habitat and farm land with huge turbines and solar panels. Hundreds of millions of tons of concrete, steel, copper, fiberglass and “rare earth” minerals would be needed to build them and thousands of miles of new transmission lines to get the expensive renewable electricity to distant cities. Because the turbines and panels only work 10-30% of the time, back up natural gas generators would also be needed, meaning still more raw materials.

Even worse, all this pain would bring no benefits. Using global warming alarmists’ own computer models, climatologist Chip Knappenberger calculated that even an 83% reduction in US carbon dioxide emissions would result in global temperatures rising just 0.1 degrees F less by 2050 than not cutting US carbon dioxide emissions at all.

That’s because CO2 emissions from China, India and other countries would quickly dwarf America’s job-killing reductions. These nations are building a new coal-fired power plant every week and putting millions of new cars on growing networks of highways - to modernize, reduce poverty, improve human health, and ensure that families, offices, schools and hospitals have electricity. Germany plans to build 27 new coal-fired power plants by 2020, and Italy expects to double its reliance on coal by 2015.

Moreover, the 0.1 degree temperature reduction assumes rising CO2 causes global warming - a belief that thousands of scientists vigorously challenge, because there is little actual evidence to support the thesis.

Of course, some will gain from penalizing, taxing and hyper-regulating our economy. Al Gore and others involved in emission trading stand to make billions, from trillions of dollars in cap-and-trade transactions. Coastal states and companies that don’t rely on coal will benefit, as will companies that get excess or low-cost emission permits and can sell these allowances for handsome profits. Well-paid bureaucrats will have “green jobs” - as will scientists, eco-activists and renewable energy companies, who will share $6-10 billion annually in taxpayer cash, as long as they continue to conduct biased climate research, issue dire warnings about global warming cataclysms, and build wind and solar projects.

Besides massive pain for no gain, cap-tax-and-trade will create an intrusive Green Nanny State that destroys jobs, reduces personal freedoms, and hobbles economic opportunities and civil rights. Our Earth is cooling. Our economy is in the tank. Congress and the White House need to stop hyperventilating about global warming, and let the free market get our economy back on track.

See PDF here. See also these two posts “Modelers History of Climate Change” here and “Al Gore, Junk Science Huckster” here.

Paul Driessen is senior policy adviser for the Committee For A Constructive Tomorrow (CFACT), which is sponsoring the All Pain No Gain petition against global-warming hype. He also is a senior policy adviser to the Congress of Racial Equality and author of Eco-Imperialism: Green Power - Black Death.

|