The Irish Times

Crops are suffering but few here are convinced global warming is to blame

“We may not raise a bushel of grain here this year but it will not be because of global warming,” says Kenny Henriksen, a crop and livestock farmer in Jewell County, Kansas.

Henriksen is meeting five farmer friends at Pinky’s coffee shop in the close-knit town of Courtland, population 340, for one of their regular get-togethers. They discuss farming matters such as how much they get for a bushel (about 25kg) of corn.

Just 40 miles east of the geographic centre of the 48 United States on continental America, Courtland has fared better than many towns where crop production has been threatened by a severe two-year drought across Kansas and other states on the US plains and midwest.

Farmers in Courtland draw on surface water to feed their crops, and don’t need to drill for water like their counterparts in western Kansas. They have also invested heavily in centre pivots, the spider-like rotating sprinkler systems that dot the land, watering areas of up to half a mile wide.

Kansas, the 15th-largest US state by size and 33rd by population, is the country’s largest wheat producer and sixth-largest corn producer.

The state traditionally makes up almost a fifth of the total US wheat production, yielding a crop worth about $1 billion a year.

This year the state will struggle to reach its typical production levels. Kansas and her neighbouring states - Colorado to the west, Nebraska to the north and Oklahoma to the south - are enduring a severe drought or worse, according to official US climatology statistics.

The shortage of moisture on the land is threatening the new crop planted last autumn and recent data suggests there is no sign of rain coming any time soon, threatening millions of acres of wheat.

The US government has designated 1,297 counties across 29 states as disaster areas, making farmers eligible for billions of dollars of low-interest emergency loans.

The government also subsidises crop insurance for farmers, which, along with high crop prices, has saved many communities. Farmers are also paid federal grants on a per-acre price for turning their farms into conservation grasslands to prevent over-farming and to ease the strain on water supplies.

Rainfall

The average rainfall across Kansas is normally between 15 and 35 inches of rain a year. Last year just 11 inches fell on average, coupled with an exceptionally hot summer of soaring temperatures.

By the time the Republican River reaches the farmers in northern Kansas from Colorado via the many wells dug in Nebraska, there is not enough water to nourish their farms.

In the face of this devastating drought and climate-related disasters, President Barack Obama has marked the fight against climate change high on his list of second-term goals.

“Some may still deny the overwhelming judgment of science, but none can avoid the devastating impact of raging fires, and crippling drought, and more powerful storms,” he said in his recent inaugural speech, drawing much focus as part of his ambitiously progressive plan.

The farmers in northern Kansas are not convinced that climate change is to blame, however. They and their fathers suffered droughts in the 1930s and 1950s, and as a recently as 2004 - the past two years are just another cycle, they argue.

“There is a lot of scientists and PhDs wanting to claim this is climate change and we are going to be dealing with this for years. It’s not something that is in our thoughts,” says Courtland farmer Brad Peterson.

“I don’t know if I believe that global warming is the reason,” says another farmer, Richard Lindberg. “We have been held back and have been limited to the water we use in irrigating our farms.”

‘Natural phenomenon’

Further east, where the drought is much more severe, the opinion is no different.

“In western Kansas we sit to the east of the Rocky Mountains, where it is drier. I remember the 1955/56 drought and 1988. My dad went through the 1930s and had to move to the west coast,” said Ron Neff, a farmer in Selden, 150 miles west of Courtland.

“It is a natural phenomenon. They want to talk about carbons and needing to take pollutants out of the air but I don’t think it is connected.”

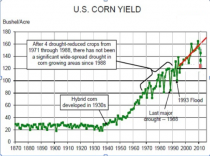

In 2008, one of the better harvest years, Neff produced about 130 bushels per acre of “dryland corn”; last year the land yielded just 15 bushels an acre on average.

Rise in temperatures

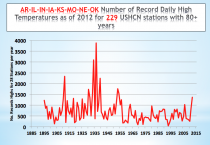

Chuck Rice, a professor of soil microbiology and a climate change expert at Kansas State University in Manhattan, Kansas, says there is no doubt that droughts are cyclical but temperatures clocked last year in the most recent dry spell have beaten historical records.

“The records weren’t just slightly broken; they were significantly higher,” he said.

Icecap Note: No sir only in the stations that were not around in the 1930s to 1950s.

The increased CO2 has helped invigorate crop and make them more DROUGHT RESISTANT.

Corn yields were down modestly despite the worst drought since perhaps the middle 1950s. They were much lower in the worst hot lower, but despite the broad coverage of drought, for the US the yields were comparable to the 1900s and well above the levels of 1988 and the 1950s and 1930s. Of course a lot of the improvement in hybrids, better practices, increased irrigation, better fertilizer and disease controls.

Some farmers acknowledge that this drought is the worst they have ever seen, he says, though he accepts that most argue that it is no different from anything that went before.

“n the heartland of the US that is the prevailing view among many because we have these cycles all the time,""said Rice. “But our analysis over 100 years shows we are seeing longer growing periods, with earlier springs and later falls. With a longer growing season you are going to need more water.”

Farmers aren/t convinced, and in a “Red” state like Kansas, Republican supporters believe Obama’s concerns about climate change are driven by something else.

“Everything he says is for his agenda,” says Kenny Henriksen, without elaborating, before sipping on a coffee in Pinky’s diner.