May 31, 2011

Mary’s Peak Snow

By George Taylor, CCM, Applied Climate LLC

Mary’s Peak, west of Corvallis, is the tallest peak in the Oregon Coast Range at about 4100 feet. There is an interesting local legend connected with snow on Mary’s Peak:

An Oregon State University (OSU) professor promised an “A” to every student in his spring term class if snow was still visible atop Mary’s Peak (as viewed from Corvallis) on June 1st. Apparently it happened only once in the professor’s career. It happened again in 1999, and then occurred again in 2008. In fact, snow was visible in 2008 almost to the end of June.

My friend Dave Twining is a graduate of OSU (PhD in Atmospheric Sciences) and a retired military officer who spends his time growing wine grapes (and making wine) and flying. He also knows a LOT about weather. In 2008 Dave sent me the following note, and gave me permission to use it.

Hi George,

I thought you might be interested in an addition to your report of some weeks ago on the long lasting snowpack on Mary’s Peak. I often fly over it and had noted, in mid-winter, that the snow depth, as judged by the little building at the parking lot appeared to be about 8 ft deep instead of the normally observed 1-2 ft after a storm. The snow there is more representative than that at the very top of the peak for the wind blows most of it off in that exposed position. Long after the snow was no longer visible from the valley, I could see, from the air, snow fields of perhaps an acre or two somewhat below and to the northeast of the trail to the top. During July these fields diminished but on my final flight on July 21st I saw a patch approximately 25 x 10 ft still remaining.

Although, as you well know, the winter was neither unusually cold nor wet, there did appear to me to be an unusual proportion of storms with a snow level of just below 4,000 ft. On very wet winters there seem to me to be a large number of storms with a high freezing level while on some very cold winters there may be snow to the valley floor but the relatively few inches deposited in these moisture-limited storms make little relative contribution to the mid-altitude zone snow-pack.

Dave

This year we have seen another cool, wet spring. On May 30, 2011, I drove up Mary’s Peak and took the following pictures at the parking lot a few hundred feet below the summit.

Rather amazing for almost June 1. By the way, snow is visible atop the Peak from Corvallis, so barring a very rapid warming, we’ll have another “June 1 snow spottings,” the third in 13 years.

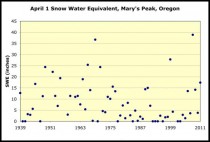

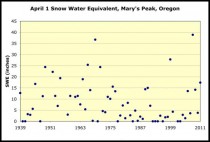

But what about long-term snow conditions? Mary’s Peak has a “Snow Course” site operated by USDA NRCS (http://www.wcc.nrcs.usda.gov) with data back to 1939. They don’t report the June 1 snow pack (it’s usually gone anyway), but below are the snow water equivalent (SWE) reports for April 1 every year.

According to Phil Mote of OSU,

There’s a peak about 4100 feet - Mary’s Peak one of the hills in the coast range of Oregon, and the only location in Oregon where U.S. government snowpack measurements go back. It used to be fairly common for the April 1st survey on Mary’s Peak to have quite a bit of snow. By the 1980’s it was getting common to have no snow on April 1st.

Notwithstanding that Mary’s is one of hundreds of snowpack sites, stopping that trend in the 1980s certainly gives a different picture than if the last several decades are included!

The article went on to say

Philip Mote explained how colleagues in California, led by climatologist David Pierce of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, were able to determine, using climate models, that the snowpack melt his own team had observed in the western United States was due to the warming temperature caused by our own greenhouse gas emissions. Snowpack melt is expected to accelerate, he added.

Not this year, anyway!

Icecap Note: SIO’s model that Phil Mote thought supported his claims, was tuned to exaggerated CO2 ‘forcing’ and very likely totally ignored the PDO cycle, the real snow driver for the western United States.

Also see this response by Dr. Gordon Fulks to George’s story:

Dear George,

Thanks for the photos of Mary’s Peak. The Snow Water Equivalent (SWE) chart for Mary’s Peak certainly shows the influence of a positive Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO) from about 1977 to 2005. Professor Mote’s contention that after 1980 it was common to have no snow on April 1st is born out by the data. What he would rather not have anyone recognize is the return of a substantial snowpack in recent years, much like that from the years 1945 to 1977. Did we stop burning fossil fuels in 2005, or have we just entered another cold cycle (negative PDO)?

No wonder Mote would not answer my questions at his USGS seminar at Portland State University last week!

Gordon

Gordon J. Fulks, PhD

Corbett, Oregon USA

P.S. Doesn’t this argue that Oregon needs a State Climatologist (like you) who will report ALL the facts and not just those that favor the perspective of those paying him? Of course, Oregon does not have a State Climatologist anymore, perhaps because the ruling class does not think we need one. They know that our climate is warming relentlessly, and Phil Mote and his prophets of doom will continue to predict it regardless of reality!

May 30, 2011

Increasing evidence that green growth strategies are job killers

Opinion by Peter Foster, Financial Post

The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development - whose members and affiliates now represent 80% of world trade and investment - this year celebrates its 50th anniversary. It seems to have come a long way from its original, noble purpose. The organization had its roots in the desire, after the Second World War, not to repeat the mistakes made after the First. Instead of demanding reparations from Germany, the Allies decided that what was needed was to encourage peaceful European co-existence and reconstruction. This approach was the brainchild of George C. Marshall, who had been U.S. Army chief of staff during the war, and subsequently became secretary of state, then secretary of defense. He won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1953.

Green alarmists such as Al Gore (who, astonishingly, also won the Peace Prize, in his case, in 2007, for stoking climate hysteria) often maintain that what is needed is a new Marshall Plan, only its objectives would be the reverse of those of George Marshall. The OECD seems more than happy to get with the new anti-Marshall program. It has now become a full-blown advocate of “sustainable development,” which is code for an anti-market ideology of less freedom and more bureaucratic control of the industries the Marshall Plan promoted.

Sustainable development was given its imprimatur by the United Nations-based, and socialist-packed, Brundtland Commission, which led to the mammoth 1992 UN environmental and development conference at Rio. Out of Rio emerged, among many other interventionist initiatives, the Kyoto Accord to control climate by restricting industrial output, and thus growth and jobs.

The OECD’s new sustainable orientation is confirmed by a report released this week on “Green Growth” (along with a “Better Life Index,” whose ideological slant was dissected in this space yesterday by William Watson). The report, and adjunct documents, propose ever-expanding bureaucratic co-ordination and monitoring of economic development at every level. However, there are major problems with this rationalist Utopia. The first is increasing evidence that climate science may have been manipulated; the second is that green growth is based on a model of government-promoted industrial strategy that has consistently failed since Adam Smith pointed to its shortcomings more than 200 years ago.

The Green Growth report makes clear that it is designed to support next year’s Rio+20 meeting, which will again take place in Brazil. “The OECD Green Growth Strategy,” says the report, “leverages off the substantial body of analysis and policy effort that flowed from the Rio conference 20 years ago.” Green Growth is claimed to be sustainable development’s “operational policy agenda.” The problem is that sustainable development has never had an operational definition.

Super-bureaucrats tend to specialize - like Al Gore - in simply ignoring inconvenient truths. This is typified in the Green Growth report’s assertion that the results of last year’s climate meeting at Cancun, at which a successor to Kyoto was to be agreed upon, “give reason to be optimistic that progress can be made.” In fact, Cancun represented the utter collapse of the Kyoto process.

It is ironic that one of the most incisive critics of climate-change science and policy is the British academic David Henderson, a former head of economics at the OECD. Meanwhile the OECD itself produced a report in 2003 that suggested that government-funded R&D added nothing to growth. And yet the Green Growth report is predicated on governments’ ability not merely to successfully identify and fund technologies of the future, but to set the “right” market prices to achieve their God-like aim of regulating both resource use and the global environment. Such aspirations have to be set against the actual havoc being wrought by green industrial policies such as biofuel subsidies, which have hit the poor hardest. Still, bureaucracies thrive and expand not by solving problems but by creating and purporting to address them, and by seeding like-minded institutions.

The OECD report notes that “Creating a global architecture that is conducive to green growth will require enhanced international co-operation.” Further work “will be based on a deepened collaboration with other international organizations, including the UN, the World Bank and the Global Green Growth Institute.”

The Global Green Growth Institute was set up by Korea last year as part of President Lee Myung-bak’s modest renewable energy vision not just for Korea but the world. You can understand President Myung-bak’s enthusiasm once you realize the sorts of benefits it holds for Korean companies. For example, Samsung secured a multi-billion dollar “sweetheart” wind and solar deal with the Ontario government that depends on Ontario hydro consumers paying huge multiples of the regular price for electricity via feed-in tariffs. That’s what the green growth strategy’s aspirations of “changing the payoffs in the economy” seems to mean. Favoured companies get paid off.

There is increasing evidence of what economic theory, and history, already suggests: that green growth strategies are job destroyers. In fact, this is not inconsistent with one of the Brundtland commissioners’ desire to “stop industrial civilization as we know it,” but it is an awfully long way from what George C. Marshall had in mind when he set out to rebuild European industry from the devastation of “brown” fascism.

May 29, 2011

Key Evidence of Global Warming Fraud

By Roger F. Gay

I was disappointed upon seeing a Global Warming “science” pitch recently published in Politico. Cold shoulder for climate change was written by sports writer turned outdoors, travel and entertainment reporter turned environmental journalist Darren Samuelsohn.

I won’t pick apart details of the entire article. It’s based on the old propaganda template: warmers are scientists, skeptics are right-wing ideologues. No mention of the much larger number of professional scientists and engineers who have gone from skeptical to calling the whole thing a fraud. In Samuelsohn’s world, warmers and their climate theories have been “exonerated” and the U.N.’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) is slated to rise in public status again.

Sameulsohn’s background - about as far from scientifically educated as possible - is rather typical for environmental journalists. The rank and file tend to drive the ad nauseam element of Global Warming Propaganda - the endless repetition of an idea in the hope that it will begin to be taken as the truth. What else are they qualified to do? We can kind-of understand this serving up of a previous season’s warmed over nonsense by someone without enough knowledge to be embarrassed by it. It’s a living, right?

So I doubt he had a clue that his article contained one of the most basic bits of evidence that the global warming scare is a complete fraud and the IPCC is a scam.

“We need to equip ourselves with the ability and capacity to deal with the heightened scrutiny...which we have been subjected to recently,” IPCC Chairman Rajendra Pachauri said earlier this month during a conference in Abu Dhabi.

Warmers tend to think of science as magic. Chant the word “science” enough and a cow pie should become the Mona Lisa if that’s what you say it is. But what is it about (real) science that implies such overwhelming credibility? If your answer is “the scientific process” then congratulations; you’re light-years ahead of environmental journalism.

Scientific process: If you’re asking, “What’s that?” then let me give you a hint. Skepticism and scrutiny are essential to the process. If ideas are not exposed and tested with skepticism and scrutiny, it isn’t science. A “skeptic” is the the more likely scientist than the “open-minded” unskeptical believer. The mere fact that a Nobel Peace Prize recipient says something doesn’t make it true. That an article is “published in a peer-reviewed scientific journal” does not make everything in it true either. Publications communicate ideas, which are then subject to skepticism and scrutiny. That’s scientific process.

The word of a “scientific committee” cannot be presumed truth. The so-called “scientific consensus” on global warming is meaningless (and still would be even if it actually did favor their argument as they insist). A good example of scientific perspective on such things is illustrated by Einstein’s response to a 1931 pamphlet entitled “100 authors against Einstein.” The pamphlet was commissioned by the German Nazi Party as a clumsy contradiction to Relativity Theory that did not fit the canons of the “Aryan science.” Similarly, the IPCC and modern leftist political operatives define acceptable scientific views to conform with a political and economic agenda and support it with a claim of a consensus view. Einstein’s answer; “If I were wrong, then one would have been enough.”

Scientific fact is not determined by appointments and elections. It didn’t matter how many Nazi supporters lined up against him or how strong their influence on public discussion. Nor does the past few decades of political influence through biased funding and its impact on the number of scientific journal articles determine the truth about global warming. Science is not conducted by committee and certainly not by political appointees in an intergovernmental panel.

What IPCC Chairman Rajendra Pachauri reveals in his statement is that scrutiny has been missing from the IPCC process - something many of us “skeptics” already knew. The IPCC was established in 1988. That makes 23 years of non-science. The problem isn’t confined to United Nations’ activities and their reports that warmers treat as the bible of climate “science.” It’s found throughout the entire chain of “climate science” activities and it’s been intentional and systematic. (That’s also an important part of what was exposed to the general public through Climategate.) “Science” is the basis of their claim of credibility, and it’s the one thing they’ve avoided doing.

Some of the warmers have Ph.D.s. In fact, there are plenty of them, and they understand all this too. The global warming scam isn’t just the product of uneducated sports writers trying to make a living. It is a fraud. Science is something done by scientists. But who is a scientist and who is not, is not determined by who holds what scientific degrees. Degrees don’t make scientists. Scientists are people who actually do science. Having made claims to scientifically established facts without subjecting them to the rigors of scientific process is not science. The people who do it are not scientists. They are frauds.

May 29, 2011

Food security and climate change

Scientific Alliance

Food security is once again - rightly - a high profile issue. The projected rise of the world’s population to 9 billion or more has been flagged as a concern for some time, but has largely failed to capture the headlines until recently. However, with a series of steep commodity prices rises occurring since 2008, it has risen to the top of the agenda for many policymakers and begun to reach the public consciousness.

The basic challenge is well-known: to feed another two billion people in a world with increasing meat consumption, with minimal use of new farmland. This is compounded by two other factors, the apparent slowing of the historical rate of yield increase from conventional plant breeding and the enthusiasm of governments to divert food crops to produce biofuels.

Based on the IPCC view, climate change is also projected to place further strains on world agriculture. Changing weather patterns are expected to reduce yields or effectively eliminate farming in some marginal areas as they become drier and temperatures exceed the tolerance level for certain crops. To set against this, though, is the parallel northwards move of the limit for crop growth and the likely opening up of large areas of productive land for agriculture, together with the yield-boosting effect of higher carbon dioxide levels (as exploited commercially by greenhouse growers).

Recently there has been a report in the Guardian (Food prices driven up by global warming, study shows) that the negative impact of climate change is not just theoretical but has already been detected. This references Lester Brown’s Earth Policy Institute, specifically Plan B 3.0: mobilising to save society (so – with apologies to non-UK readers - contradicting Marks and Spencer). However, it appears to be based on work to be published in Science by a Lobell et al from Stanford University (Climate Trends and Global Crop Production Since 1980).

Professor Tim Wheeler of the Walker Institute for Climate System Research at the University of Reading and deputy chief scientist at the UK Department for International Development (the only ministry with a prospect of significant budget increases, to the disquiet of some) told the Guardian “The research provides evidence of big shifts in wheat and maize production”. Given his government advisory role, his comments are likely to reflect official thinking.

The article goes on to say “The study, published in the journal Science, examined how rising temperatures affected the annual crop yields of all major producer nations between 1980 and 2008. Computer models were used to show how much grain would have been harvested in the absence of warming. Overall, yields have been rising over the last decades and the models took this into account. The scientists found that global wheat production was 33m tonnes (5.5%) lower than it would have been without warming and maize production was 23m tonnes (3.8%) lower. Specific countries fared worse than the average, with Russia losing 15% of its potential wheat crop, and Brazil, Mexico and Italy suffering above average losses. Some countries experienced lower production of rice and soybeans, although these drops were offset by gains in other countries....The losses drove up food prices by as much as 18.9%, the team calculated, although the rise could be as low as 6.4% if the increased carbon dioxide in the atmosphere strongly boosts plant growth and yields - a factor that is not well understood by scientists.”

Note the reference to computer models: this study is not based on hard data, but a statistical analysis using a number of ‘what ifs’. The premise is, according to the article, that “higher temperatures can cause dehydration, prevent pollination and lead to slowed photosynthesis,” which is one of the thrusts of Lester Brown’s work, mentioned earlier.

Quoting from his Plan B 3.0, “Agriculture as it exists today has been shaped by a climate system that has changed little over farming’s 11,000-year history. Crops were developed to maximize yields in this long-standing climatic regime. As the temperature rises, agriculture will be increasingly out of sync with its natural environment. Nowhere is this more evident than in the relationship between temperature and crop yields.” Most readers will find this an overly romanticised view of farming which takes no account of, for example, the Roman and Medieval warm periods. Looking further at the few references quoted in support, he relies on a handful of relatively old papers and a speech at a 2002 conference on sustainable food security. The only reference to the effect of temperature on yield is a paper which reports lower rice yields with higher night time temperatures. Conclusions about global yields of a range of crops must, we can only hope, be based on firmer evidence than that.

A useful point of reference is the FAO statistical database FAOSTATand there seems little evidence from this to support such conclusions. Over the period 1990 to 2009, the global area of farmland used for cereals production fell slightly, from 708 million hectares to 699 mha. However, over the same period, the cereals harvest rose from 1.95 billion tonnes to 2.49bn tonnes. The increase was not consistent, but neither is there any pattern which could be correlated to average temperatures; the biggest gains have been in recent years.

A similar analysis for the period 1970 to 1989 shows a global cereals harvest increasing from 1.2bn tonnes to 1.9bn tonnes on essentially the same land area. The increase was much higher in percentage terms and also larger in absolute terms than in the more recent period, but we should remember that this was the period of the green revolution, when the introduction of dwarf wheat and rice varieties transformed much of Asia from a region of recurrent famine to one of self-sufficiency (albeit still with unacceptably high levels of poverty and malnutrition).

On a related topic, Oxfam will soon launch a new campaign, called simply Grow, with the ambitious goal of ‘fixing the food system, forever’. It is difficult to argue that Oxfam has not played a very important role for many poor people over the years but, like most of the rest of the development sector, it has become very politicised. The first aim of the campaign - helping people to grow their own food better - is unarguably a good thing, but the fact that there have been decades of such work with little real change to the lives of the poorest suggests that this fails to address the root causes of poverty and food security.

Beyond that, the campaign lapses into idealism, with a wish to create ‘a global food system that takes action when food prices rise beyond the means of poor families, and which stops food companies abusing their power’. A belief in central planning and the superiority of the public sector does not look like a good way forward. And the third strand, to achieve a ‘fair, global deal on climate change...to prevent a devastating impact on agriculture’ simply chimes with the current pessimism among many environmentalists (and, indeed, the political and scientific establishments) and will do nothing to help farmers.

It seems clear that the work of Oxfam, the Earth Policy Institute and the Stanford scientists is underpinned by a world view that takes it as given that humans - or at least, those of us in richer countries - are a blight on the planet, with our supposed dominant effect on the natural climate system simply the most egregious example. We face enormous challenges over coming decades, but we also have a great capacity to overcome them. As a first step, we need to encourage people to remove their blinkers and realise that other views can be equally valid.

May 28, 2011

Climate Progress blog shuts down - all previous comments disappear

Anthony Watts, WattsUpWithThat

It appears the mendacious Joe Romm has been given new marching orders by Center for American Progress Big Brother Blog: “Think Progress”. From what I make of it, it seems the management realized that CP just wasn’t holding much readership, as it looks like the same 30 commenters or so frequent the place. Sooo...the spin is on. Joe’s doing his best to make his forced merger under Think Progress look like a win.

“Prettier”? Heh. Me thinks this is Joe’s “lipstick on a pig” moment.

What is most strange though, is this note about comments disabled.

Not only are comments disabled, they are gone, all of them, from the present to when the blog started in 2006. That may be a temporary condition, but we’ll see. When I moved from Moveable Type back in October 2007 to WordPress.com, everything remained in place, comments and all and is still there today.

You gotta love a guy like that that treats his user community like they don’t exist anymore.

Joe’s last post was about his vision of Memorial Day, 2030

That reminds me to remind everyone (and especially Joe) to be sure to fly your flag this coming Memorial Day, to honor those who gave so much, but have not been forgotten (nor disappeared).

I look forward to seeing more “high quality” climate articles on Think Progress, like this one:

ThinkProgress discussion of the tornado outbreak - click here for the full article. ...and, while the rescue operations were underway, this is how Brad Johnson updated his article - disgusting.

See post and comments.

|