Dec 19, 2017

Trump Cuts Climate Change, Sets National Health Priorities

Jane M. Orient, MD

Update: See also this from the Manhattan Contrarian by Francis Menton on this issue here.

The Trump Administration has announced the removal of climate change from the list of national security threats. This Obama Administration priority was responsible for policies such as trying to make the U.S. Navy a ‘Great Green Fleet’ running on “advanced biofuels.” The rationale was that global warming (renamed “climate change") was a bigger threat than terrorist attacks or North Korean nuclear-tipped intercontinental ballistic missiles, and that running aircraft carriers on a blend of 90 percent diesel and a very costly additive made from beef fat or palm oil would somehow protect against bad weather over the next century.

Climate change is also supposed to be the greatest global health threat, according to a consortium of medical organizations and Pope Francis, who oppose President Trump’s decision to withdraw from the Paris climate agreement. The predicted climate disruption is evidently worse than poverty, AIDS, poor sanitation, Ebola, or other emerging infectious diseases, in their opinion. It is, indeed, supposed to worsen those factors, for example by increasing the range of insect vectors like mosquitoes. (Never mind that mosquitoes thrive in Alaska and Siberia.)

Fifty years of public health gains could be reversed, warn 22 authors in the prestigious British journal The Lancet, if we don’t take urgent action to limit emissions of carbon dioxide from the fuels that now power 80 percent of the world’s economy (coal, oil, and natural gas - “fossil fuels"). The “planet still has time to heal,” they say, but we are on a “countdown.”

It’s a little hard to get the public aroused about heat waves 50 years from now, while people are shoveling “heart attack snow,” or trying to keep from freezing to death. Deaths from cold are historically far more prevalent than deaths from heat waves. Arctic cold is setting dozens of records for low temperatures in the U.S. Northeast, and a Siberian cold front has already killed dozens in Central and Eastern Europe, with 50-year record lows as far south as Bulgaria.

European countries such as England and Germany that are taking the lead on turning to “renewables” - the German Energiewende - prices for fuel and electricity have soared. Many people have to choose whether to “heat or eat.”

It takes an apocalyptic threat to get people to accept economic hardship. The UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and prominent U.S. academics constantly trumpet a litany of horribles that will supposedly be inevitable without drastic, immediate changes. California and other jurisdictions claim that they will take unilateral action to “protect” or “stabilize” earth’s climate despite Trump’s opposition. Dozens of Congressmen of both parties have joined the Climate Solutions Caucus to oppose Trump.

President Trump’s priority is energy security - or energy dominance for America. His initiatives include:

Removing climate alarmism messages from official government websites;

Cutting the funding of the multi-billion dollar infrastructure devoted to “finding” human-caused climate change and promoting an agenda of global energy rationing;

Demanding that the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) include all scientific viewpoints instead of silencing critics of the “sky is falling’ narrative; and Rolling back Obama regulations and policies designed to kill the coal industry and suppress use of America’s petroleum and natural gas resources.

The world’s greatest killer is poverty. Prosperity depends on adequate, reliable, affordable energy. Income rises with increased use of hydrocarbons (and CO2 emissions), and life expectancy rises with income.

But perhaps even more important to public health than energy is scientific integrity. Trump is basically at odds with the self-anointed scientific authorities who demand that their computer models be accepted as gospel and used to impose trillions of dollars in costs. This authoritarianism garbed in science is in itself a disaster. Moreover, the models give wrong answers, and the policy recommendations are all pain for no gain. To demonstrate this, Doctors for Disaster Preparedness posed 10 Climate Change IQ Questions to the Climate Solutions Caucus, inviting them to seek a refutation from their go-to experts. So far, not a single argument has been presented.

President Trump’s initiatives on energy and climate challenge medical and public health authorities to prove their anti-carbon case, instead of just imposing it on the world. That is both a national security and a health priority.

Jane M. Orient, M.D. is executive director of the Association of American Physicians and Surgeons. She also is president of Doctors for Disaster Preparedness, and is the editor of AAPS News, the Doctors for Disaster Preparedness Newsletter, and Civil Defense Perspectives. She is the managing editor of the Journal of American Physicians and Surgeons.

Dec 10, 2017

Wildfires are a natural part of nature though bad policies make the results worse

Wildfires have been in the news almost every late summer and fall. Every year, the media blames ‘climate change’. Governor Brown says these Raging Wildfires are “The New Normal,” for which he Blames Climate Change. The truth is the fires are normal and the damage done is greater because more people want to escape the urban areas and live in the hills among the trees. Ironically, government policies driven by extreme environmentalists like Governor Brown are making the fires worse. See more here.

This month, fires have spread to the Los Angeles region as strong Santa Ana winds and dry air caused the fire to spread rapidly.

Enlarged

Earlier in the fall, the wildfires that swept through California in October of 2017 burned 200,000 acres and destroyed or damaged more than 5,500 homes. It was widely reported these fires were the worst and most extensive and deadly ever. And, it was widely reported that these fires were greatly worsened by Global Warming.

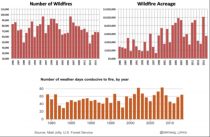

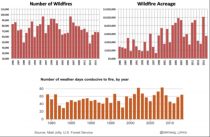

Actually, the number of fires and acreage affected since 1985 show the number of fires is actually down slightly though the acreage burned had increased before leveling off the last 20 years. The NWS tracks the number of days where conditions are conducive to wildfires when they issue red-flag warnings. It is little changed.

When it comes to considering the number of deaths and structures destroyed, the seven-fold increase in population in California from 1930 to 2017 must be noted. Not only does this increase in population mean more people and home structures in the path of fires, but it also means more fires. Lightning and campfires caused most historic fires; today most are the result of power lines igniting trees. The power lines have increased proportionately with the population, so it can be reasoned that most of the damage from wild fires in California is a result of increased population not Global Warming. The increased danger is also greatly aggravated by poor government forest management choices.

Large-scale deadly fires are not unique in the nation’s history.

“In 1871, during the week of Oct. 8-14, it must have seemed like the whole world was ablaze for residents of the Upper Midwest. Four of the worst fires in U.S. history all broke out in the same week across the region. The Great Chicago Fire, which destroyed about a third of the city’s valuation at the time and left more than 100,000 residents homeless, stole the headlines.

But at the same time, three other fires also scorched the region. Blazes leveled the Michigan cities of Holland and Manistee in what has been referred to as the Great Michigan Fire, while across the state another fire destroyed the city of Port Huron. The worst fire of them all, however, might have been the Great Peshtigo Fire, a firestorm that ravaged the Wisconsin countryside, leaving more than 1,500 dead - the most fatalities by fire in U.S. history.” Link.

Weather and normal seasonal and year-to-year variations brings fires to the west every year and other areas from time to time. This past winter was a very wet one, and in the mountains in the west, a snowy one. Wet winters cause more spring growth that will dry up in the dry summer heat season and become tinder for late summer and early fall fires before the seasonal rains return.

The number of fires and acreage affected since 1985 show the number of fires is actually down slightly though the acreage burned had increased before leveling off the last 20 years. The NWS tracks the number of days where conditions are conducive to wildfires when they issue red-flag warnings. It is little changed.

Enlarged

ROLE OF DEVELOPMENT AND GOVERNMENT POLICIES

People find it desirable to live in the quiet beauty of the hilly wooded developments away from the big cities-- unfortunately in areas that are vulnerable to wildfires when the strong seasonal winds blow at the end of the dry season.

The danger is aggravated by bad environmental and governmental policies. Last summer, Governor Brown vetoed a bi-partisan bill to help subsidize PGE tree removal from near power lines and transformers as the law requires. The downed trees and power lines/transformers are believed to be the cause of at least some of the fires as the sparks ignited the dry brush and the cinders and sparks are carried by the same winds that brought down the lines and transformers.

The National Park Service changed its policy in 1968 to recognize fire as a natural ecological process. Fires on federal lands were to be allowed to run their courses where possible.

In a May, 2017 congressional hearing, Rep. Tom McClintock, R-Calif., said, “Forty-five years ago, we began imposing laws that have made the management of our forests all but impossible.” “Time and again, we see vivid boundaries between the young, healthy, growing forests managed by state, local, and private landholders, and the choked, dying, or burned federal forests’”

McClintock said. “The laws of the past 45 years have not only failed to protect the forest environment - they have done immeasurable harm to our forests.” In an October, 2017 House address, McClintock pinned the blame of poor forest management on bad 1970s laws, like the National Environmental Policy Act and the Endangered Species Act. He said these laws “have resulted in endlessly time-consuming and cost-prohibitive restrictions and requirements that have made the scientific management of our forests virtually impossible.”

Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke has promoted a change to forest management policies, calling for a more aggressive approach to reduce the excess vegetation that has made the fires worse. See more.

Ironically if CO2 has played a role, as a fertilizer, it has increased the greening in wet water years like 2016/17.

See Cliff Mass rebut the claims that the CO2 is driving increasing wildfires.

Nov 30, 2017

Green Energy Train to Energy Poverty

Joseph D’Aleo, CCM, AMS Fellow

As I noted in Joe’s blog we are making a major effort to work with the nation’s most respected scientists to prepare rebuttals to claims from environmental groups and government agencies and to formerly reply to the CAP, USCSSP NCA travesties. As is always the case though we get accused of being shills for big oil, all work that we do is pro bono. If you can help us defer the costs of our efforts, please use the donate button in the left column. Even small amounts are appreciated.

Update: As one of the rebuttals to common claims, we hear and read that Australia and Europe are great examples of how green is good.

Here is our rebuttal:

Claim: Europe and Australia are benefiting from their green energy policies. We should follow their example.

Facts:

One commonly heard claim is that the green energy policies are working where they have been implemented and should be a model for our national energy policies. They claim a green miracle domestically in California and savings for ratepayers in the RGGI states and high profile countries like Germany, Denmark and Australia where governments have implemented aggressive plans to replace reliable fossil fuel energy with renewables.

Instead, these policies have brought skyrocketing energy prices, hurting most those who can afford it the least, while green energy suppliers and investors in renewables rake in windfall profits. With higher prices, many companies leave the countries (or states) eventually leading to higher unemployment. Some of the hardest hit early adapters are rethinking their compliance to the original plans. In the U.S., California and the RGGI states pay the highest electricity prices in the nation. The lower gasoline and heating fuel prices thanks to fracking is hiding this for now. Meanwhile, the enviro lobby has targeted fracking and pushing electric autos.

If one were to look at the real story in the model countries and states, they would run away from the radical green agenda.

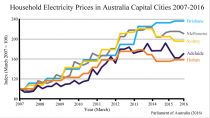

Australia’s renewable energy program has been a disaster - raising electricity prices and leading to widespread blackouts and crises when electricity was unavailable for over a week at a time, because the wind was not blowing, demand was spiking, and the country did not have nearly enough backup power during heat waves in 2016 and 2017.

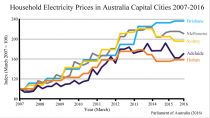

According to data from the Parliament of Australia, household electricity prices for five of the seven capital cities increased between 60 and 235 percent over the last nine years. These increases were driven by programs to force adoption of renewable energy.

Power prices in the Australian renewable energy paradise of South Australia have driven 102,000 South Australians to beg for help from food charities, according to a major South Australian newspaper. Those people have been forced to skip meals so that they can pay their soaring electricity bills.

Enlarged

See Back to Bolted-Down industries story here.

In Europe, the rapid growth of generously subsidized renewable projects has left end users, taxpayers or energy companies with steeper bills while private investors have secured lucrative profits.

Germany’s first wind turbines will lose eligibility for surcharge subsidies paid by customers in 2021, after which only a few installations can be operated at a profit, according to the Energy Brainpool consultancy. At that point they will have to get more subsidies or will have to be shut down.

Because Germany has invested so much in expensive, unreliable wind and solar energy - and is shutting down its nuclear power plants - the country is actually building huge new coal-fired generating units that burn low-energy lignite and emit large amounts of carbon dioxide.

The result of these policies is that German businesses and families now pay the second highest electricity price in Europe, after Denmark: 45 cents per kilowatt-hour = five times what Americans pay for coal and gas-fueled electricity and nearly three times what they pay in California, Connecticut and New York.

In the Czech Republic, the government reacted to a “solar boom” by restricting feed-in tariffs and imposing a windfall tax that often hit investors that had just entered the market. The backlash affected all renewables, explaining why wind farms such as JRD’s Vaclavice project have been so rare in recent years. “Renewables were completely discredited,” declared Jan Mladek, former minister and the architect of the Czech government’s energy policy. At the end of 2010 the state said ‘we have made a mistake and you will pay for it’,” says Marek Lang, director of JRD’s energy division. Similar stories across the region have given renewable energy a bad name and triggered lawsuits and arbitration actions by foreign investors complaining of erratic and retroactive changes in subsidy regimes.

This has enabled politically powerful coal and nuclear lobbies to mount a rearguard action to persuade governments to support their interests. This has met little resistance, as environmental movements are often much weaker than in western Europe and energy pricing is even more sensitive due to lower incomes.

In Poland, the populist rightwing government has defended the country’s coal industry and is hostile to Brussels’ green agenda.

Enlarged

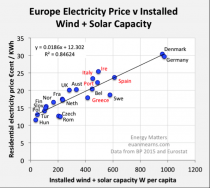

The more the move the renewable, the greater the cost to ratepayers and the more unreliable the power supply because the wind does not always blow or sun shine.

Enlarged

If Americans had to pay German or Denmark’s electricity rates, the results would be devastating. For example:

Virginia’s 665,000-square-foot Inova Fairfax Women’s and Children’s Hospital pays about $1,850,000 per year for electricity at 9 cents per kilowatt-hour. At 17 cents (the price in California, Connecticut and New York), the hospital would have to pay $3,500,000. That’s a $1.6-million difference. At the German rate of 45cents per kWh, Inova would have to pay $9,250,000 per year - a whopping, destructive, unsustainable $7.4-million increase in the cost of doing business and serving patients.

How many dozens or hundreds of employees would Inova have to lay off, to make up for that difference? How many emergency and other services would it have to eliminate? What would that do to patients, especially to the poorest families?

How many workers would be laid off in America’s factories, refineries and other businesses if electricity prices double, triple or quintuple? How many families would be driven into severe energy poverty? How many businesses or entire industries would have to close? How many people would die every winter, because they could no longer afford to heat their homes properly, especially in frigid Mid-western states?

-----------

How environmental activists and liberal politicians are ‘Grubering’ America on climate and energy

MIT professor Jonathan Gruber, who was an advisor to Obama on the Obamacare act mocked the “stupidity” of American voters and boasted of the Obama administration’s ability to take advantage of it. They did that for Obamacare but also, in partnership with the environmental left for their regulatory siege, the CPP and the Paris treaty. The latest act from the last administration was the NCA CSSR atrocity.

The global warming agenda has nothing to do with science and everything to do with politics and ideology. Nearly 6 decades ago, President Eisenhower in his 1961 farewell address to the nation, in which the president famously warned of the danger to the nation of a growing armaments industry referred to as a “military-industrial complex,” he talked about the risks posed by a scientific-technological elite.

He noted that the technological revolution of previous decades had been fed by more costly and centralized research, increasingly sponsored by the federal government. Eisenhower warned.

“Partly because of the huge costs involved, a government contract becomes virtually a substitute for intellectual curiosity.” While continuing to respect discovery and scientific research, he said, “We must also be alert to the equal and opposite danger that public policy could itself become the captive of a scientific-technological elite.”

The Club of Rome was an organization formed in 1968 consisting of heads of state, UN bureaucrats, high-level politicians and government officials, diplomats, scientists, economists and business leaders from around the globe. It raised considerable public attention in 1972 with its report The Limits to Growth.

The club’s mission was “to act as a global catalyst for change through the identification and analysis of the crucial problems facing humanity”. They decided that more centralized control was needed under one world government. In their book “The First Global Revolution” in 1991, they wrote:

“In searching for a new enemy to unite us, we came up with the idea that pollution, the threat of global warming...would fit the bill...It does not matter if this common enemy is “a real one or...one invented for the purpose.”

172 countries attended the Rio Summit in 1992 and agreed on the Climate Change Convention, which in turn led to the UN IPCC, the failed Kyoto Protocol and then the Paris Agreement.

The former head of NOAA Dr. Jane Lubchenco proved Eisenhower correct in his warning that public policy could itself become the captive of a scientific-technological elite. In her 1999 address to the AAAS when she served as its president:

“Urgent and unprecedented environmental and social changes challenge scientists to define a new social contract. This contract represents a commitment on the part of all scientists to devote their energies and talents to the most pressing problems of the day, in proportion to their importance, in exchange for public funding.”

Former Washington State Democratic governor Dixy Lee Ray saw the second Treaty of Paris coming. “The future is to be [One] World Government with central planning by the United Nations,” she said. “Fear of environmental crises - whether real or not - is expected to lead to compliance.”

One World Government under the auspices of the UN is now called Agenda 2030.

It is favored by the democrats and some establishment republicans. UN Sustainable Development Goals aim to reduce inequality worldwide by forcing individual governments and citizens alike to share their wealth. Western (US) taxpayers are targeted and their wealth would be redistributed internationally while their economies are cut down to size. Big government would control all aspects of life, where people can live, how many children couples could have, energy used, the food supply, even some have proposed how much money we could keep for the work we do, etc.

UN Climate Chief Christiana Figueres stated bluntly, “Our aim is not to save the world from ecological calamity but to change the global economic system...” In simpler terms, she intends to replace free enterprise, entrepreneurial capitalism with UN-controlled centralized, One World government and economic control.

UN IPCC official Ottmar Edenhofer presented an additional reason for UN climate policies. “One has to free oneself from the illusion that international climate policy is environmental policy, it is not”. It is actually about how “we redistribute de facto the world’s wealth.”

H.L Mencken also was prophetic in his statements “The whole aim of practical politics is to keep the populace alarmed - and hence clamorous to be led to safety - by menacing it with an endless series of hobgoblins, all of them imaginary” and “The urge to save humanity is almost always only a false face for the urge to rule it.”

The scientific elite, housed in the professional societies, our government agencies and the universities teamed with politicians, educators and the media have created what may be the greatest hoax in the history of civilization. The latest CSSR National Climate Assessment report is perhaps the most egregious example of advocacy science in history assembling a series of wild though easily refuted claims. More to come on that.

They even invented a new science of “attribution without detection” (when you can’t find the trends you expect in the data, you claim you can read between the lines and see them anyway). This should remind you of Michigan Senator Debbie Stabenow who explained to the editorial board of the Detroit News her support for carbon dioxide restrictions designed to fight global warming. “Climate change is very real. Global warming creates volatility and I feel it when I’m flying. The storms are more volatile. We are paying the price in more hurricanes and tornadoes.”

As Detroit News contributor Henry Payne noted: “And there are sea monsters in Lake Michigan. I can feel them when I’m boating.”

Contradicting Stabenow’s claims, however, NOAA’s Storm Prediction Center reported that the number of F3 or stronger tornadoes has been declining since the early 1970s and 2013 had 142 fewer tornadoes reported than any year on record. Before this top ten Atlantic hurricane season, we had a record near 12-year period without any major hurricane landfall, beating out the 1860s by almost 4 years.

Our biggest challenge is as Mark Twain observed “It’s easier to fool people than to convince them that they have been fooled.”

The saddest result of policies based on bad science to achieve environmental dreams of a fossil fuel free world, is the effects of high energy costs that inevitably follows on the poor and middle class families.

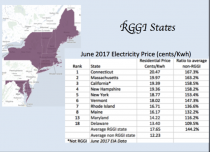

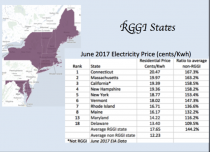

The Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI), which the northeast democratic governors claim has been a great success has the region paying the highest electricity prices in the nation (along with green California). Lower gasoline prices and heating fuel prices thanks to the fracking boom has eased the pain for now. But the environmentalists and green politicians want to stop that. It is already forbidden in New York State despite the rich Marcellus shale field that Pennsylvania is tapping into.

Enlarged

Wherever the environmental lobby wins, people lose. Power prices in the Australian renewable energy paradise of South Australia have driven 102,000 South Australians to beg for help from food charities, according to a major South Australian newspaper. Those people have been forced to skip meals so that they can pay their soaring electricity bills.

In Europe, the rapid growth of generously subsidized renewable projects has left end users, taxpayers or energy companies with steeper bills while private investors have secured lucrative profits. Over 25% of the UK households, especially pensioners are in what is called energy poverty, having to choose between heating and eating.

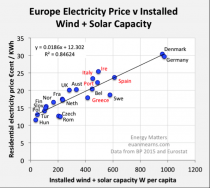

The result of these policies in Germany, businesses and families now pay the second highest electricity price in Europe, after Denmark: 45 cents per kilowatt-hour - five times what Americans pay for coal and gas-fueled electricity and nearly three times what they pay in California, Connecticut and New York. The more wind and solar, the higher the electricity prices.

Enlarged

As pundits have asked: How many workers would be laid off in America’s factories, refineries and other businesses if electricity prices double, triple or quintuple? How many families would be driven into severe energy poverty? How many businesses or entire industries would have to close? How many people would die every winter, because they could no longer afford to heat their homes properly, especially in frigid northern states?

Enlarged/

See how Paul Dreissen shows how Virginia joins the other clueless states that think they can save the world by abiding by the Paris Accord here.

------------

Why Are We Destroying Our Grid?

By Donn Dears

Or, asked differently:

Why are we destroying the most efficient, reliable and least costly system ever devised for generating and distributing electricity?

Here are some facts:

Electricity generated by wind and solar is more expensive than electricity generated using traditional methods, e.g., coal-fired, natural gas combined cycle, nuclear and hydro power plants.

Wind and solar are intermittent and unreliable methods for generating electricity that requires backup, usually with natural gas turbines, which increases costs.

Wind and solar require expensive storage to alleviate evening ramping-up by traditional methods of generation, and to permit larger amounts of renewables on the grid which increases costs.

Promoting and subsidizing PV rooftop solar, often with net-metering provisions, increases costs.

Attempting to increase the amount of wind and solar generated electricity to substantially replace traditional methods of generating electricity will require large amounts of prohibitively expensive storage.

In addition, it’s very likely that:

Adding large amounts of intermittent wind and solar will reduce the reliability of the grid. Microgrids that are being touted by environmental groups will increase costs and complexity, with few real benefits.

In the face of these facts, we are forcing wind and solar onto the grid by:

Enacting renewable portfolio standards (RPS) that require utilities to provide a steadily increasing amount of electricity from renewables, primarily wind and solar.

Subsidizing wind and solar to encourage investing in them.

Allowing RTO/ISOs to use a dispatch system that gives wind and solar preference over traditional methods of generating electricity, which is driving nuclear and coal-fired generation off the grid, and which will ultimately also drive natural gas generation from the grid.

Photo by D. Dears

So: Why are we destroying the grid?

It’s not to make electricity less costly.

It’s not to improve reliability.

It’s to cut CO2 emissions.

Global warming and climate change hysteria is causing us to destroy the most efficient, reliable and least costly system ever devised for generating and distributing electricity.

Which is also a fact.

One would think that all Americans would be interested in determining whether there is a real threat from anthropogenic global warming (AGW) or climate change.

One would think Americans might be asking: Why are we destroying the grid?

Yet the media and proponents of AGW won’t allow any debate ... And in fact, try to discourage debate by calling those who don’t agree with them deniers, or some other demeaning characterization. Additionally, they propose taking legal action against “deniers”, with some legislators demanding that “deniers” be jailed.

The brochure, Nothing to Fear from CO2, is available free, at www.powerforusa.com. It provides the history of world temperatures for the past 10,000 years together with atmospheric CO2 levels and a look at natural causes for global warming.

Oct 18, 2017

Sixty-Five Scientists Demand Reconsideration Of EPA’s Endangerment Finding

Francis Menton

Today a large group of some sixty-five top scientists sent a letter to EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt demanding that he initiate a process to reconsider the so-called Endangerment Finding of 2009.

See the Letter and the 64 signatories. We know that many more scientists would have been pleased to sign this letter if they had only known about it. Scientists may ask to have their name added by simply sending their info to THSResearch@aol.com.

Regular readers of this blog will recognize the EF as one of the most egregious and preposterous bureaucratic power grabs of all time. By the EF, EPA purported to “determine” that carbon dioxide—a colorless, odorless gas that has no known adverse health effects at any concentration you will ever experience and that is the basis for all life on earth—is a “danger” to human health and welfare. The so-called science underlying the EF is and always was a joke. See, for example my post “The ‘Science’ Underlying Climate Alarmism Turns Up Missing” from September 2016 (and multiple similar posts). Nevertheless, the EF was used by the Obama administration as the basis for, among other things, its Clean Power Plan, seeking to force the closure of all coal-fired power plants (and ultimately the closure of all power plants involving any fossil fuel). Just today, a group of about seventeen “blue” states and their environmentalist co-parties filed a brief in the D.C. Circuit (behind pay wall) seeking to compel the Trump administration to reinstate the CPP or something like it, on the grounds that the EF requires the government to regulate emissions of carbon dioxide.

Here is a link to today’s letter. And here is the full text:

You have pending before you two science-based petitions for reconsideration of the 2009 Endangerment Finding for Greenhouse Gases, one filed by the Concerned Household Electricity Consumers Council, and one filed jointly by the Competitive Enterprise Institute and the Science and Environmental Policy Project.

We the undersigned are individuals who have technical skills and knowledge relevant to climate science and the GHG Endangerment Finding. We each are convinced that the 2009 GHG Endangerment Finding is fundamentally flawed and that an honest, unbiased reconsideration is in order.

If such a reconsideration is granted, each of us will assist in a new Endangerment Finding assessment that is carried out in a fashion that is legally consistent with the relevant statute and case law.

We see this as a very urgent matter and therefore, request that you send your response to one of the signers who is also associated with a petitioner, SEPP.

Readers here will also recognize that I am serving as a lawyer for one of the Petitioners (the Concerned Household Electricity Consumers Council) seeking reconsideration of the EF. Our group issued a press release this morning simultaneous with the release of the scientists’ letter to Administrator Pruitt. Key points from our press release:

The Concerned Household Electricity Consumers Council fully endorses the recommendations of these scientists because recent research has definitively validated that: once certain natural factor (i.e., solar, volcanic and oceanic/ENSO activity) impacts on temperature data are accounted for, there is no “natural factor adjusted” warming remaining to be attributed to rising atmospheric CO2 levels. That is, these natural factor impacts fully explain the trends in all relevant temperature data sets over the last 50 or more years. At this point, there is no statistically valid proof that past increases in atmospheric CO2 concentrations have caused what have been officially reported as rising, or even record setting, global average surface temperatures (GAST)… Moreover, additional research findings demonstrate that adjustments by government agencies to the GAST record render that record totally inconsistent with published credible temperature data sets and useless for any policy purpose…

This scientifically illiterate regulation [based on the EF] will raise U.S. energy prices thereby reducing economic growth and jobs as well as our National Security… The Electricity Consumers Council therefore, based on this new scientific evidence, must insist that the EPA grant the “very urgent” request of these scientists “that an honest, unbiased reconsideration is in order.”

I won’t attempt to list here who all the letter’s signers are, but if you go to the link you will see that they are a who’s who of the top scientific people active on these issues. To the extent that credentials count for anything in today’s corrupted world, many of them have top degrees and top professorships at top institutions.

Now, perhaps you have seen the claim that “97% of scientists agree” that human-caused global warming is a crisis, or something like that. I guess that would have to mean that the alarmist team will shortly produce a responsive letter signed by in excess of 2000 comparably-qualified scientists. Don’t bank on it. No such group exists. Yes, there is a substantial government-funded clique of lightweights and charlatans that spend their lives manipulating the world temperature records and putting out fake press releases of “hottest year ever!” Undoubtedly they can exceed our group in numbers (government dollars buy a lot of loyalty and corruption). But no such group that could be assembled could remotely match our group of sixty-five for bona fide scientific heft. If they try to assemble such a group, the contrast of the real scientists versus the lightweights will be immediately apparent.

And by the way, the signing process for our scientists’ letter is still open, and we expect the number of signers to increase over time. Let the games begin!