Apr 30, 2010

Oh, Mann: Cuccinelli targets UVA papers in Climategate salvo - University Balks

By Courteney Stuart

No one can accuse Virginia Attorney General Ken Cuccinelli of shying from controversy. In his first four months in office, Cuccinelli directed public universities to remove sexual orientation from their anti-discrimination policies, attacked the Environmental Protection Agency, and filed a lawsuit challenging federal health care reform. Now, it appears, he may be preparing a legal assault on an embattled proponent of global warming theory who used to teach at the University of Virginia, Michael Mann.

In papers sent to UVA April 23, Cuccinelli’s office commands the university to produce a sweeping swath of documents relating to Mann’s receipt of nearly half a million dollars in state grant-funded climate research conducted while Mann - now director of the Earth System Science Center at Penn State - was at UVA between 1999 and 2005.

If Cuccinelli succeeds in finding a smoking gun like the purloined emails that led to the international scandal dubbed Climategate, Cuccinelli could seek the return of all the research money, legal fees, and trebled damages.

“Since it’s public money, there’s enough controversy to look in to the possible manipulation of data,” says Dr. Charles Battig, president of the nonprofit Piedmont Chapter Virginia Scientists and Engineers for Energy and Environment, a group that doubts the underpinnings of climate change theory.

Mann is one of the lead authors of the controversial “hockey stick graph,” which contends that global temperatures have experienced a sudden and unprecedented upward spike (like the shape of a hockey stick).

Neither UVA spokesperson Carol Wood nor Mann returned a reporter’s calls at posting time, but Mann - whose research remains under investigation at Penn State - recently defended his work in a front page story in USA Today saying while there could be “minor” errors in his work there’s nothing that would amount to fraud or change his ultimate conclusions that the earth is warming as a result of human activities, particularly the burning of fossil fuels.

Last fall, the release of some emails by researchers caused turmoil in the climate science world and bolstered critics of the human-blaming scientific models. (Among Climategate’s embarrassing revelations was that one researcher professed an interest in “...punching Charlottesville-based doubting climate scientist Patrick Michaels in the nose.")

Among the documents Cuccinelli demands are any and all emailed or written correspondence between or relating to Mann and more than 40 climate scientists, documents supporting any of five applications for the $484,875 in grants, and evidence of any documents that no longer exist along with proof of why, when, and how they were destroyed or disappeared.

The Attorney General has the right to make such demands for documents under the Fraud Against Taxpayers Act, a 2002 law designed to keep government workers honest. Read more here.

--------------------

Another Global Warming Scientist Slates Legal Probe by John O’Sullivan

Since the Climategate scandal establishment figures have relentlessly stymied unwelcome scrutiny by legal experts. The latest wagon-circler is Dr. Judith Curry, an esteemed member of NASA’s Climate Research Committee for over three years. Now Curry has become a self-appointed apologist for the unethical and some say, fraudulent, conduct of Penn. State University’s climate professor, Michael Mann.

In an interview with Thomas Fuller of the Environmental Policy Examiner (May 4, 2010) this well-heeled establishment scientist criticizes Virginia Attorney General, Ken Cuccinelli, for doing his job. Somehow Dr. Curry manages to fudge the line between a deliberate pre-meditated criminal fraud and an honest mistake.

Her tirade was prompted by Cuccinelli’s legal demand for access to Mann’s records from his former employers at Virginia State University where the tree-ring researcher benefited by almost $500,000 in taxpayer funding.

The Evidence Shows Probable Cause

If anyone doubts Cuccinelli’s just cause then I suggest they read the Wegman Report, those leaked Climategate emails plus the British investigation known as the Oxburgh Committee Report.

Click PDF file to read FULL report from John O’Sullivan (inc. links)

UPDATE: See AAUP and ACLU Wants Virginia to Fight Records Request here. See UVA Suggests It May Not Comply With Cuccinelli Climate-Gate ‘Witch Hunt’ here.

----------------

Scientists decry “assaults” on climate research

By Deborah Zabarenko, Environment Correspondent, Reuters

More than 250 U.S. scientists on Thursday defended climate change research against “political assaults” and warned that any delay in tackling global warming heightens the risk of a planet-wide catastrophe.

The scientists, all members of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences, targeted critics who have urged postponing any action against climate change because of alleged problems with research shown in a series of hacked e-mails that are collectively known as “climate-gate.”

“When someone says that society should wait until scientists are absolutely certain before taking any action, it is the same as saying society should never take action,” the 255 scientists wrote in an open letter in the journal Science.

“For a problem as potentially catastrophic as climate change, taking no action poses a dangerous risk for our planet,” they wrote. They said they were deeply disturbed by “recent escalation of political assaults on scientists in general and on climate scientists in particular.”

Scientists sounded a similar note on Thursday before the U.S. House of Representatives panel on energy independence and climate change. “The reality of anthropogenic climate change can no longer be debated on scientific grounds,” James Hurrell of the U.S. National Center for Atmospheric Research told the committee. “The imperative is to act aggressively to reduce carbon emissions and dependency on fossil fuels.” Read more here.

UPDATE: Australian Broadcasting Corp (ABC) News Watch reports the following:

ABC recently reported on a letter signed by 250 scientists published in the journal Science. The letter is accompanied by a photo of a lone Polar Bear on an ice berg credited to ISTOCKPHOTO.COM. The photo is a fake with the following note in the photo caption at Istockphoto: “This images is a photoshop design. Polarbear, ice floe, ocean and sky are real, they were just not together in the way they are now.” The same background is also available with one emperor penguin (HERE) or three (HERE).

What does the use of a faked photo say about the scientific credibility of the journal in question?

----------------------

The ClimateGate Scandals: What has been revealed and what does it mean?

by William Yeatman, Global Warming.org

On April 16th, the Cooler Heads Coalition and the Heritage Foundation hosted a briefing on Climategate by Dr. Patrick J. Michaels, Senior Fellow in Environmental Studies, Cato Institute and Joseph DAleo, Executive Director, ICECAP, and Consulting Meteorologist.

Dr. Patrick J. Michaels, Senior Fellow, CATO Institute

The scientific case for catastrophic global warming was already showing signs of weakening when the Climategate scientific fraud scandal broke in November 2009. This release of thousands of computer files and emails between leading global warming scientists showed evidence of data manipulation, flouting of freedom of information laws, and attempts to suppress publication of research that disagreed with the alarmist “consensus.”

Climategate has raised many questions about the reliability of key temperature records as well as the objectivity of the researchers and institutions involved, but it is far from the only global warming-related controversy. It has been followed by revelations that some of the most attention-grabbing claims in the 2007 UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) Fourth Assessment Report - the supposed gold standard of climate science - were simply made up. Before laws regulating energy use are enacted that could well cost trillions of dollars, it is crucial to understand the extent to which the alleged scientific consensus supporting global warming alarmism has been discredited by these scandals. Join us for a discussion featuring two scientists who have closely studied Climategate.

Click here to view video of the briefing. See post and more here.

Apr 28, 2010

The Association of Outgoing Radiation with Variations of Precipitation - GW Implications

By Dr. William Gray and Barry Schwartz

1. INTRODUCTION

Global warming scenarios from CO2 increases are envisioned to bring about rainfall enhancement and resulting upper tropospheric water vapor rise. This initial water vapor enhancement has been hypothesized and programmed in climate models to develop yet additional rainfall and water vapor increase. This causes an extra blockage of IR energy to space (a positive feedback warming mechanism). This additional rainfall and IR blockage is modeled to be approximately twice as large as the additional rainfall needed to balance the increased CO2 by itself. The reality of this additional warming and extra IR blockage has been questioned by many of us. This study analyzes a wide variety of infrared (IR) radiation differences which are associated with rainfall differences on different space and time scales. Our goal is to determine the extent to which the positive rainfall feedbacks as are included in the climate model simulations are realistic.

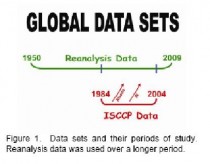

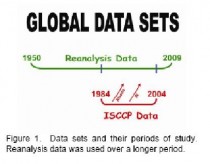

We have analyzed 21 years (1984-2004) of ISCCP (International Satellite Cloud Climatology Project) outgoing solar (albedo) and outgoing longwave infrared (IR) radiation (often referred to as OLR) on various distance (local to global) and time scales (1 day to decadal). We have investigated how radiation measurements change with variations in precipitation as determined from NCEP-NCAR Reanalysis data on a wide variety of space and time scales (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Data sets and their periods of study. Reanalysis data was used over a longer period.

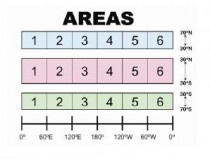

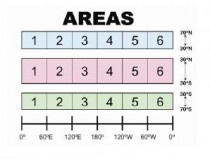

We have stratified our radiation and rainfall data into three latitudinal sections and six distinctive longitudinal areas (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Areas of study.

Infrared and albedo changes associated with rainfall variations by month (January to December) and by yearly periods for the globe (70N-70S; 0-360) as a whole and separately for the tropics (30N-30S; 0-360) have been studied. This analysis shows they are not realistic.

Above shown global tropospheric water vapor trends over the period from 1950-2009 for 300, 400 and 500mb RH.

Much more detail in paper. Click to download PDF file from William M. Gray and Barry Schwartz

Apr 27, 2010

The Laws of Physics Ably Defeat the Global Warming Theory

By John O’Sullivan

Among a steady groundswell of scientists eager to contradict the faltering greenhouse gas theory of man-made global warming, comes ‘Induced Emission and Heat Stored by Air, Water and Dry Clay Soil’ by Professor Nasif Nahle.

Oceans Drive Climate, Not Trace Gasses

The internationally-acclaimed professor, from Monterrey, Mexico, exposes the weakness of the greenhouse gas theory for its failure to consider that other processes are important in the atmospheric radiative heat transfer event. A former Harvard and UCLA graduate with degrees in science and mathematics, Nahle confidently states, “I demonstrate that the climate of Earth is driven by the oceans, the ground surface and the subsurface materials of the ground.”

Warmists Miscalculate Heat

A dwindling band of supporters of the theory of anthropogenic global warming (AGW) still cling to the discredited notion that 50% of the energy absorbed by atmospheric gases (especially carbon dioxide) is re-emitted back towards Earth’s surface, heating it up.

Nahle, whose areas of expertise ranges from Physics to Biology, Ecology, Bioeconomy and Biophysics, attacks this flawed assumption, “The problem with the AGW idea is that its proponents think that the Earth is isolated and that the heat engine only works on the surface of the ground.”

Instead, Nahle’s robust calculations prove that photon streams from oceans, the ground and other subsurface materials, both day and night, succeed in overwhelming the emission of photons from the atmosphere, returning them to space.

Laws of Thermodynamics Held Firm

Nahle, like many other respected analysts, insists that a scientific law is exactly that and cannot be ignored. While theories, like AGW, come and go dependent on their ability to withstand scrutiny. The harshest criticism made by Professor Nahle is that global warmists have absurdly discarded the accepted laws of thermodynamics to prop up their improbable theory.

The professor reminds us that, “at night time, the heat stored by the subsurface materials is transferred by conduction towards the surface, which is colder than the unexposed materials below the surface. The heat transferred from the subsurface layers to the surface is then transported by the air by means of convection and warms up.”

Thereafter, the direction of the radiation emitted by the atmosphere can only go upwards into the upper atmosphere and then out into deep space. Nahle says we are then forced to conclude that, “atmospheric gases do not cause any warming of the surface given that induced emission prevails over spontaneous emission.”

No Sustained Rises in Global Temperatures

Nahle’s findings are supported by the failure of greenhouse gas theorists to evince from global thermometer records any sustained rise in world temperatures other than the short blip of 1975-95. This failure, plus the ongoing data handling scandals that have mired climatologists in accusations that they falsified temperature records, has seen respected scientific publications, such as ‘New Scientist’ retreat from the tarnished theory.

Indeed, warmist doomsayer and controversial Climategate scientist, Kevin Trenberth recently was compelled to concede he had ‘lost’ 50% of the warming that his colleagues had predicted. The leaked Climategate emails reveal Trenberth lamenting that it was a “travesty” that the Earth had failed to show any signs of “catastrophic” warming as the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) had warned.

Scientists Misled By Poor Data Handling Skills

Moreover, a recent independent British report into the Climategate scandal found that an elite clique of UN climate scientists who had championed the AGW theory had poor statistical-handling skills and had cherry-picked data to bolster their “subjective” claims.

Nahle neatly sums it up, “The warming effect (misnamed “the greenhouse effect") of Earth is due to the oceans, the ground surface and subsurface materials. Atmospheric gases act only as conveyors of heat.”

Nahle, N., Didactic Article: ‘Induced Emission and Heat Stored by Air, Water and Dry Clay Soil,’ Biology Cabinet Organization (May 21, 2009). Read more at Suite101: The Laws of Physics Ably Defeat the Global Warming Theory

--------------------

Kiwigate is a Carbon Copy of Climategate

The New Zealand Climate Science Coalition (NZCSC) in its article ‘NIWA Challenged to Show Why and How Temperature Records Were Adjusted’ (February 7, 2010) provides its readers with an insight into the climate scandal dubbed ‘Kiwigate.’ NIWA is New Zealand’s National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research and is accused of repeatedly frustrating NZCSC in its attempts to get government climatologists to explain how they managed to create a warming trend for their nation’s climate that is not borne out by the actual temperature record.

According to NZCSC, climate boffins cooked the books by using the same alleged ‘trick’ employed by British and American doomsaying scientists. This involves subtly imposing a warming bias during what is known as the ‘homogenisation’ process that occurs when climate data needs to be adjusted.

Homogenisation Explained

When such data adjustments (homogenisations) are made, scientists must keep their working calculations so that other scientists can test the reasonableness of those adjustments. According to an article in Mathematical Geosciences (April 2009) homogenisation of climate data needs to be done because “non-climatic factors make data unrepresentative of the actual climate variation.” The article tells us that if the raw data is not homogenised (or, in this case, “fudged” according to sceptics) the “conclusions of climatic and hydrological studies are potentially biased.”

According to the independent inquiry into Climategate chaired by Lord Oxburgh, it was found that it was the homogenisation process itself that became flawed because climatologists were overly guided by “subjective” bias.

Andrew Bolt, writing for Australia’s Herald Sun (November 26, 2009) commented that the Kiwigate scandal was not so much about “hide the decline” but “ramp up the rise.”

Jim Salinger: Another ‘Phil Jones’?

Bolt goes on to report, “Those adjustments were made by New Zealand climate scientist Jim Salinger, a lead author for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).” Salinger was dismissed by NIWA this year for speaking without authorisation to the media. Salinger once worked at Britain’s CRU, the institution at the centre of the Climategate scandal. Salinger became part of the inner circle of climate scientists whose leaked emails precipitated the original climate controversy in November 2009. In an email (August 4, 2003) to fellow disgraced American climate professor, Michael Mann, Salinger stated he was “extremely concerned about academic standards” among climate sceptics.

Circling The Bandwagons?

NZCSC made a joint press release with the Climate Science Conversation Group (December 18, 2009) accusing NIWA of publishing, “misleading material.” The two organisations claim that NIWA had been “defensive and obstructive” in requests to see New Zealand climate scientists’ data. NZCSC goes on to report, “The main objective of our temperature study was not to show that the raw data has been tampered with, even though that opinion was emphasised and cannot yet be excluded.”

On January 29, 2010, in what seemed like a reprise of the Phil Jones debacle at Britain’s Climate Research Unit, the Kiwi government finally owned up that “NIWA does not hold copies of the original worksheets.”

Kiwigate Mimics Climategate

Kiwigate appears to match Climategate in three essential characteristics. First, climate scientists declined to submit their data for independent analysis. Second, when backed into a corner the scientists claimed their adjustments had been ‘lost’. Third, the raw data itself proves no warming trend. Thus we may reasonably infer a ‘carbon copy’ of Climategate.

NZCSC explained their frustrations in trying to get to actual truth about what had happened with New Zealand’s climate history, “NIWA did everything they possibly could to help us, except hand over the adjustments. It has turned out that there was actually nothing more they could have done - because they never had the adjustments.... None of the scientific papers that NIWA cited in their impressive-sounding press releases contained the actual adjustments....”

After a protracted delay NIWA was forced to admit it has no record of why and when any adjustments were made to the nation’s climate data. Independent auditors have shown that older data was fudged to make past temperature appear cooler, while modern data was inexplicably ramped up to portray a warming trend that is not backed up by the actual thermometer numbers. Sceptics are asking how can it be that climate scientists in different countries at the opposite side of the world are facing extraordinarily similar data fraud allegations?

Unsatisfactory Outcome

‘The world is left with more questions than answers. Website,’Scoop’ echoed the sentiments of other climate sceptics by arguing that because New Zealand’s climate data adjustments cannot be verified (peer-reviewed) like CRU’s, then they are thus just as worthless. With so many climatologists having ‘lost’ their calculations, no one can now replicate their methods and confidence in climate science has evaporated. In addition, further scandalous revelations with Glaciergate and other ‘gates’ have mired the IPCC in an alleged international data fraud conspiracy that undermines the entire theory of man made climate change.

The knock-on effect worldwide is a fall away in voters’ concerns about ‘global warming’ issues so that international governments are losing their mandate for cap and trade taxes to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from fossil fuels.

References:

Bolt, A. ‘Climategate: Making New Zealand warmer,’ Herald Sun (November 26, 2009), accessed online April 26, 2010.

Costa, A.C. and A. Soares, ‘Homogenization of Climate Data: Review and New Perspectives Using Geostatistics,’ Mathematical Geoscience, Volume 41, Number 3 / April, 2009.

New Zealand Climate Science Coalition, ‘NIWA Challenged to Show Why and How Temperature Records Were Adjusted’ (February 7, 2010), accessed online April 26, 2010.

NZCSC & Climate Science Conversation Group; Press Statement of December 18, 2009; accessed online ( April 26, 2010).

Salinger, J. Climategate email Filename: 1060002347.txt. (August 4, 2003).

Read more at Suite101: Kiwigate is a Carbon Copy of Climategate

Apr 24, 2010

Scientist says Arctic getting colder

UPI

MOSCOW, April 23 (UPI)—A Russian scientist says the Arctic may be getting colder, not warmer, which would hamper the international race to discover new mineral fields. An Arctic cold snap that began in 1998 could last for years, freezing the northern marine passage and making it impassable without icebreaking ships, said Oleg Pokrovsky of the Voeikov Main Geophysical Observatory. “I think the development of the shelf will face large problems,” Pokrovsky said Thursday at a seminar on research in the Polar regions. Scientists who believe the climate is warming may have been misled by data from U.S. meteorological stations located in urban areas, where dense microclimates creates higher temperatures, RIA Novosti quoted Pokrovsky as saying. “Politicians who placed their bets on global warming may lose the pot,” Pokrovsky said. See post here.

-------------------

Global Cold Wave May Be Looming

By Meteorologist Art Horn

The global warming enthusiasts have been shouting that as man injects more and more carbon dioxide into the air we will warm the atmosphere beyond recognition. But now in an ironic twist of fate and timing nature is set to crush all of that talk. A blast of arctic cold may soon encase the earth with an icy grip not seen for nearly 200 years. This is not idle fantasy or alarmist 2012 babble. There are natural forces in nature that are awakening…all at the same time! These forces let loose one at a time can cause the earth to cool and bring about harsh winter conditions. However if they all break free of their captivity at once the effects could be felt not just in the winter but all year long and for several years to come. Should the following words prove to be prophetic the social and economic impact of these powerful forces working together may make history. The airline industry in Europe is already feeling the effects.

On March 20th a volcano erupted on the island of Iceland. This eruption has become much more violent in the last few days. The ash cloud from this volcano has caused the cancellation of tens of thousands of airline flights in Europe. Some estimates say the industry could lose over 200 million dollars a day due to cancelled flights. A volcano erupting in Iceland is not an uncommon event. The island is one of the few spots where the mid oceanic ridge’rears up out of the water revealing its violent personality. However this volcano is different. It can act as a predictor of future much more explosive and consequential activity. The volcano’s name is, and this is no joke Eyjafjallajokull. This volcano has only erupted three times since the 9th century. The last eruption was in the early 1820s. What is alarming about this most recent eruption is that in the past it has been followed by a much larger eruption of the nearby Katla Volcano. Katla has blown its top many times on its own, usually every 60 to 80 years. The last time was 1918 so it’s overdue to explode. Magnus Tomi Gudmundson is a geophysicist and the University of Iceland and an expert on volcanic ice eruptions and he says “There is an increased likelihood we’ll see a Katla eruption in the coming months or a year or two, but there’s no way that’s certain”. He also said “from records we know that every time Eyjafjallajokull has erupted Katla has also erupted”.

The reason this is ominously significant is that these giant eruptions can change the atmosphere on a planetary scale for years. Mount Laki is another large volcano in Iceland that has a history of producing climate changing eruptions. In the early summer of 1783 Laki erupted releasing vast rivers of lava. The explosive volcano also ejected a massive amount of volcanic ash and sulfur dioxide into the air. The eruption was so violent that the ash and sulfur dioxide were injected into the stratosphere some 8 miles up. This cloud was then swept around the world by the stratospheric winds. The result was a significant decrease in the amount of sunlight reaching the earth’s surface for several years. That reduction in sunlight brought about bitter cold weather across the northern hemisphere. The winter of 1784 was one of the coldest ever seen in New England and in Europe. New Jersey was buried under feet of snow and the Mississippi river froze all the way down to New Orleans! Historical records show that similar conditions existed during the following winter.

There are other eruptions that have produced similar short term climate consequences. Mount Tambora is in Indonesia. This volcano erupted with cataclysmic force in April 1815. It was the largest volcanic eruption in over 1,600 years. It was also during a time of very low solar activity known as the “Dalton Minimum”. The following year was called “the year without a summer”. During early June of 1815 a foot of snow fell on Quebec City. In July and August lake and river ice were observed as far south as Pennsylvania. Frost killed crops across New England with resulting famine. During the brutal winter of 1816/17 the temperature fell to -32 at New York City.

Mount Pinatubo exploded in June of 1991 after four centuries of sleep. The resultant cloud of volcanic ash belched into the stratosphere pounded the global temperature down a full one degree Fahrenheit by 1993. Record snowfall buried southern New England during the winter of 1993/94. Those same records were shattered just two years later in the winter of 1995/96 from the effects of the reduced sunlight.

If Eyjafjallajokull induces an eruption of Katla that event alone could force global temperatures down for 3 to 5 years. But there is much more at work here. We have just exited the longest and deepest solar minimum in nearly 100 years. During this minimum the sun had the greatest number of spotless days (days where there were no sunspots on the face of the sun) since the early 1800s. The solar cycle is usually about 11 years from minimum to minimum. This past cycle 23 lasted 12.7 years. The long length of a solar cycle has been shown to have significant climate significance. Australian solar researcher Dr. David Archibald has shown that for every one year increase in the solar cycle length there is a half degree Celsius drop in the global temperature in the next cycle. Using that relationship we could expect a global temperature drop of one degree Fahrenheit by 2020. That would wipe out all of the global warming of the last 150 years!

But that is not all. There is a third player in this potential global temperature plunge. Since the Autumn of 2009 to the current time we have been under the influence of a moderately strong El Nino. El Nino is a warming of the water in the Pacific Ocean along the equator from South America to the international dateline. El Nino’s warm water adds vast amounts of heat and humidity to the atmosphere. The result is a warmer earth and greatly altered weather patterns around the world. The current El Nino is predicted to fade out this summer. Frequently after an El Nino we see the development of La Nina, the colder sister of El Nino. La Nina’s cooler waters along the equatorial Pacific act to cool the earth’s temperature.

If a La Nina develops this summer this could be the third leg of a natural convergence of forces not seen since the early 1800s. The sun has experienced its longest and most pronounced solar minimum in nearly 100 years. Research indicates this deep, long minimum will be followed by at least 10 years of colder weather. Mount Eyjafjallajokull in Iceland has started erupting. History has shown that every time Mount Eyjafjallajokull erupts the nearby more powerful and explosive Katla follows. The vast volcanic cloud thrust into the stratosphere by this explosion partially blocks out the warming rays of the sun and causes global temperature to plummet. El Nino is frequently followed by La Nina. The current El Nino is forecast to be over this summer.

The stage could soon be set for a confluence of cold inducing forces. A La Nina with its chilling waters combined with the effects of a weaker sun combined with a possible major eruption in Iceland. If all or two of these work together the earth could plunge into a period of bitter cold not seen for two hundred years. Forecasts of natural phenomena are notoriously difficult. However a unique set of natural circumstances have a chance to unify into an icicle of cold very soon. All eyes will be on Iceland to see if Katla awakens from its long sleep. If it does a worldwide cold wave may result and any talk of global warming will fade from the headlines.

Apr 23, 2010

Global warming scare industry suppresses benefits of CO2

By Kirk Myers, Seminole County Environmental News Examiner

Bombarded by the incessant fear-mongering of the global warming industry, many people now see carbon dioxide (CO2) as evil incarnate - the bane of civilization and source of an ever-growing list of planetary problems - from erupting volcanoes and tectonic earthquakes to shrinking sheep and reduced circumcision rates.

The climate experts, joined by their lazy and interminably gullible allies in the mainstream media, have managed through guile and deception to orchestrate a successful fear campaign against a trace atmospheric gas that is essential to all life on earth. Around the clock, these self-anointed saviors of Mother Earth hector mankind, admonishing the thoughtless masses for increasing CO2 to “climate tipping” levels that will eventually bake our planet unless we cork our gaseous emissions, shut down industry and hand over more of our paychecks to the Gods of Cap and Trade.

Hypnotized by their “science is settled” theory, the self-professed climate experts have abandon the practice of science and morphed into political-scientist advocates, manipulating and fine-tuning their research so it matches their pre-ordained conclusions. (A brief look at the Climategate e-mails, made public last November, illustrates the abysmal level to which climate science has descended.)

The snakeoil scientists have worked indefatigably to give CO2 - a molecular friend of mankind - a dirty name. They have hidden the facts of CO2 from the people, lest they awake to the grand AGW deception. And they have studiously engaged in a premeditated attempt to deceive the innocent (they have already deceived themselves), always with a finger to the wind and an eye on the next juicy research grant. Here are a few truths about the benefits of CO2, routinely suppressed or glossed over in the hysterics-laden propaganda about catastrophic global warming (a term renamed “climate change” as global temperatures leveled off and began to decline) disseminated by agenda-driven scientists and politicians and their chief ally, the negligent and slothful reporter.

CO2 not a pollutant - Atmospheric CO2 is essential to life on earth and is directly responsible for the food we eat and the oxygen we breathe. Plants feed on CO2 and emit oxygen as a waste gas, and humans and animals breathe oxygen and exhale CO2. When plant-growers want to stimulate plant growth, they introduce more CO2.

Current CO2 deficiency - With a current CO2 concentration of 388 ppm, Earth’s atmosphere is CO2 deficient. (During the last 600 million years, only the Carboniferous Period and our current age, the Quaternary Period, have experienced CO2 levels less than 400 ppm.) Millions of year ago, when CO2 concentrations were 10 times higher than today, plant life flourished. Falling, not rising, CO2 levels, would seriously impact life as we know it, reducing agricultural production for a growing population and increasing the likelihood of food shortages and famine.

CO2 non-threatening at 10,000 ppm - CO2 is not a threat to humans unless it reaches 50,000 ppm (exhaled breath is about 45,000 ppm). Sailors in U.S. submarines experience no harmful effects while routinely working in spaces where CO2 concentrations reach 8,000 ppm. Concert-goers in a packed auditorium are steeped in 10,000 ppm. The recommended level in workspaces for an eight-hour day is 5,000 ppm, and the typical officer worker inhales air containing up to 2,500 ppm. So why the fuss about the potential doubling of life-enriching CO2? (Contrary to the AGW theory, runaway temperatures are not a catastrophic side-effect of CO2 increases.)

Higher CO2 equals more food - Rising concentrations of atmospheric CO2 stimulate plant grown, resulting in higher agricultural yields. As Dr Craig Idso and Dr. Keith Idso have shown, a 300 ppm increase in atmospheric CO2 will increase the yield of nearly all food crops by 30 to 50 percent. According to both researchers, the expected rise in CO2 concentrations by 2050 will increase world agricultural production, but to levels that barely will be enough to prevent widespread famine. Efforts to limit CO2 would retard both industrial and agricultural production.

A 300 ppm increase in CO2 results in a 30- to 50-percent increase in the yield of most food crops

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) has determined that a one percent increase in CO2 boosts crop yields by eight percent, translating into a 33-pound-per-acre yield per 1-ppm rise in CO2. The USDA also found that a field of corn in full sunlight consumes all of the CO2 within three feet of the ground. The corn will stop growing unless the surrounding air is stirred constantly by wind currents. In fact, the plants are harmed at CO2 concentrations of 240 ppm, and they die at 160 ppm.

In short, more CO2 puts more food on the table. Human life, in terms of length and quality, has improved dramatically since the massive burning of fossil fuels. In their zeal to curb CO2 emissions, the Green movement seeks to deprive humanity of life-sustaining nutrition.

Rising CO2 is natural - Atmospheric CO2 has risen steadily for the past 18,000 years - long before fossil-fuel-burning factories and power plants dotted the landscape. Most of the greenhouse effect is natural – resulting from water vapor and other trace gases. Human-generated greenhouse gases account for roughly 0.28 percent of the greenhouse effect.

Man-made CO2 comprises about 0.117 percent of this total, and human contributions of other gases - for example, methane and nitrous oxide - add another 0.163 percent. Compared to water vapor, which makes up 95 percent of greenhouse gases, CO2, at roughly 3.6 percent, is a piddling amount. Capping CO2 emissions in a vain attempt to “stop global warming” would hobble industrial output and lower our standard of living, while having almost no impact on the Earth’s climate, which, according to recent reports, has entered a “cold mode” that could last 20 to 30 years.

Short atmospheric lifetime - The residence time of bulk atmospheric CO2 is roughly five years, a fact previously acknowledged by former IPCC Chairman Dr. Bert Bolin. This figure is steadfastly ignored or disputed by scientists who base their findings on carbon-cycle computer models that project theoretically longer lifetimes - 50 to 200 years, or longer - than those actually measured in the real world. Their model-manipulated conclusions are contradicted by observational data and geo-chemistry.

As Tom V. Segalstad, associate professor of resource and environmental geology at the University of Oslo, notes: “The non-realistic carbon-cycle modeling and misconception of the way the geochemistry of CO2 works simply defy reality, and would make it impossible for breweries to make the carbonated beer or soda ‘pop’ that many of us enjoy (Segalstad, 1998).”

With such short CO2 residence times (about one fifth of the CO2 pool is exchanged every year between different sources and sinks), it is impossible for human activity to be the cause of rising CO2 levels. As Segalstad observes: “Concerning the Earth’s carbon cycle, the anthropogenic CO2 contribution and its influence are so small and negligible that our resources would be much better spent on other real challenges that are facing mankind.”

Contemptuous of any scientific data that would derail their globalist schemes, the international banking establishment and their political cronies are moving ahead at flank speed to fleece American citizens through a cap-and trade system that will drive their energy bills through the roof - all in the name of fighting a conjured-up bogeyman called “global warming.”

Initially, the cap-and-trade swindle will drive up energy costs by as much as $1,700 per year for many families. By 2035, those costs could escalate to more than $6,000 annually. And what about the economic losses caused by soaring energy costs and declining industrial output? Some independent analysts are projecting the loss of millions of jobs as the nation’s GDP reverses direction, throwing already hard-hit Americans out of their homes and onto the street.

As Lord Christopher Monckton, a former adviser to Margaret Thatcher, observes: “To prevent that half a Fahrenheit degree of [predicted] warming imagined by the UN, we’d have to shut down—and shut down completely—the entire world economy for a decade. Right back to the Stone Age, and without even the right to light a carbon-emitting fire in our caves . . . “The economic cost of trying to mitigate imagined ‘global warming’ by reducing our CO2 emissions must in all circumstances extravagantly, monstrously, absurdly outweigh any conceivable climatic benefit. It is this central economic truth . . . that the media and the politicians can no longer ignore.” See Kirk’s post here. See how it is supported by this presentation by Chemist Dr. Martin Hertsberg.

|