Sep 01, 2010

Johnson’s stance is the correct one

Letter to the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel Online

As scientists, we write to support U.S. Senate candidate Ron Johnson’s correct view on natural factors of climate change as reported in the Journal Sentinel (Page 1B, Aug. 17; Page 1A, Aug. 21).

This is not a debate about politics or about a belief system. Objective science informs us that the so-called consensus viewpoints offered by the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change about man-made carbon dioxide being the dominant factor of climate change is largely a political conclusion and not likely a scientifically correct one.

If global temperatures are supposedly affected by rapidly rising atmospheric CO2 concentrations but the warming has ceased over at least the last decade, then something more important than atmospheric CO2 must be driving climate change. This is why the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration reported Aug. 13 that “greenhouse gas forcing fails to explain the 2010 heat wave over western Russia.”

We wish to emphasize that many peer-reviewed publications exist that support the minimal role of atmospheric CO2 as a cause for the weather and climate that we experience. Extremist views only serve to induce panic about climate change, and the unwillingness to address the real science only leads to spurious claims that “the science is settled.”

For example, a paper published Aug. 19 in Geophysical Research Letters by a scientist from the California Institute of Technology shows that even the apparently drastic decrease of summer-autumn Arctic sea ice is not unprecedented but merely an effect of Arctic Ocean geography.

We therefore applaud Senate candidate Ron Johnson’s stance against CO2-induced climate change.

Eight scientists signed this letter; they noted that their university affiliations are for identification purposes only and are not an endorsement of the letter. The signers are: Willie Soon, Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics; Scott Armstrong, Wharton School at University of Pennsylvania; Robert Carter, James Cook University, Australia; Susan Crockford, University of Victoria, Canada; Kesten Green, University of South Australia; Nils-Axel Morner, Stockholm University, Sweden; George Taylor, Oregon State University, retired; and Mitchell Taylor, Lakehead University, Canada.

Aug 31, 2010

How Harvard’s Code of Ethics Differs from UVA and Penn State with respect to Michael Mann

By Charles Battig, MD

An insight into the apparent difference in how “scientific misconduct” at Harvard University is handled, and how it has been handled at Penn State and the University of Virginia in the matter of climatologist Michael Mann is now available.

Harvard professor of psychology Marc Hauser was found “solely responsible for eight instances of scientific misconduct” involving the “data acquisition, data analysis, data retention, and the reporting of research methodologies and results” according to the August 20, 2010 statement by Harvard dean Michael D. Smith. This finding was issued based on a faculty investigating committee study. The report noted that it began with an “inquiry phase” in response to “allegations of scientific misconduct.” It seems that there were allegations of “monkey business” in his research on monkey cognition. Three papers by Hauser, presumably peer reviewed, will need to be corrected or retracted according to Dean Smith. The academic fate of the professor is yet to be decided.

In contrast, the two reviews of the behavior of climatologist Michael Mann at Penn State seemed primarily focused on his data housekeeping habits and openness to sharing his data and analysis methodology. He was found to have acted within the ‘accepted practices within the scientific community for proposing, conducting, or reporting research.” The issues of data acquisition and analysis validity were not pursued; the number of awards and publications Mann received was cited as evidence of the validity of his work.

At the University of Virginia an “inquiry phase”, such as noted in the Harvard protocol, was initiated by Virginia Attorney General Ken Cuccinelli into the possible misuse of public funds by Mann in his pursuit of employment by the University and his use of such funds in his research activities there. Virginia state law gives wide discretion to the AG in the initiation of investigations into suspected misuse of state funds. This request was met with claims of impingement on sacred academic freedom, and chilling the environment for academic research in general by the university and its various supporters. Rather than welcome the chance to dispel the suspicion of scientific misconduct and protect its academic reputation, the university enlisted a high powered D.C. legal team to fight the AG request in court.

While this legal process plays out, the court of public opinion must wonder why the openness and direct dealing with such allegations exhibited by Harvard is not the model for the University of Virginia. Harvard is shown to be a scientifically open and self policing university; UVa is hiding behind its self -righteous claims of academic freedom and legal barricades. Whose research will the public more likely trust?

Charles Battig, M.D.

President, Piedmont Chapter

Virginia Scientists and Engineers for Energy and Environment

Charlottesville, VA

Aug 30, 2010

11 Year Cycle in Hot Summers

By Joseph S. D’Aleo, CCM

We have seen hot summers in 1933, 1944, 1955, 1966, 1977, 1988, 1999, 2010. Notice a pattern? The years are 11 years apart.

This 11 year cycle may be a coincidence but if so a 1 in 256 chance one. In some years the heat was concentrated in one month (1966 it was July), in others it was throughout.

What else has an 11 year cycle? - the sun of course. The solar cycles average 11 years. When new solar cycles begin the new spots are in higher solar latitudes and gradually move equatorward. During transitions you typically have old cycle spots near the equator and new cycle spots at higher latitudes.

The 11 years above have been during these transitions. A coincidence? We’ll leave it to our solar expert readers to speculate whether this is solar driven and possible mechanisms. Other common elements in some of the years include an El Nino winter giving way to a La Nina summer and strong rebound from a very negative winter negative Arctic Oscillation (AO) pattern.

See so-called butterfly diagram with positions of sunspots by year enlarged here.

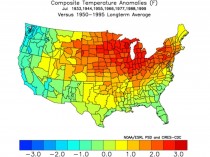

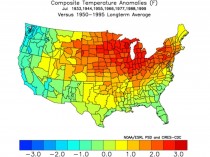

Compositing those years gives you this warm summer signal.

See enlarged here.

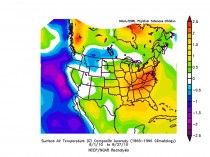

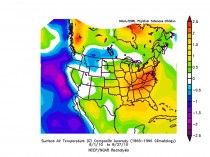

The actual anomalies through August 30 showed the warmth further south. This may be because of a continuation of strong high latitude blocking (negative NAO) as evidenced by the warmth in northeast Canada.

See enlarged here.

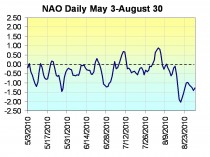

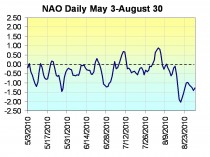

Indeed a plot of the daily NAO as obtained from NOAA CPC shows a predominant negative NAO. This forces everything else further south in North America and the Atlantic.

See enlarged here.

In July, a negative NAO means a hot southeast. By winter, it means cold.

A continuation of this blocking may make the upcoming La Nina winter more interesting. The winters tend to be cold in the west and north, warmer in the southeast. See more here.

Aug 30, 2010

Himalayan glaciers melting deadline ‘a mistake’

By Pallava Bagla in Delhi

The UN panel on climate change warning that Himalayan glaciers could melt to a fifth of current levels by 2035 is wildly inaccurate, an academic says.

J Graham Cogley, a professor at Ontario Trent University, says he believes the UN authors got the date from an earlier report wrong by more than 300 years.

He is astonished they “misread 2350 as 2035”. The authors deny the claims.

Leading glaciologists say the report has caused confusion and “a catalogue of errors in Himalayan glaciology”.

The Himalayas hold the planet’s largest body of ice outside the polar caps - an estimated 12,000 cubic kilometres of water.

They feed many of the world’s great rivers - the Ganges, the Indus, the Brahmaputra - on which hundreds of millions of people depend.

‘Catastrophic rate’

In its 2007 report, the Nobel Prize-winning Inter-governmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) said: “Glaciers in the Himalayas are receding faster than in any other part of the world and, if the present rate continues, the likelihood of them disappearing by the year 2035 and perhaps sooner is very high if the Earth keeps warming at the current rate.

It is not plausible that Himalayan glaciers are disappearing completely within the next few decades

Himalayan glaciers’ ‘mixed picture’

“Its total area will likely shrink from the present 500,000 to 100,000 square kilometres by the year 2035,” the report said.

It suggested three quarters of a billion people who depend on glacier melt for water supplies in Asia could be affected.

But Professor Cogley has found a 1996 document by a leading hydrologist, VM Kotlyakov, that mentions 2350 as the year by which there will be massive and precipitate melting of glaciers.

“The extrapolar glaciation of the Earth will be decaying at rapid, catastrophic rates - its total area will shrink from 500,000 to 100,000 square kilometres by the year 2350,” Mr Kotlyakov’s report said.

Mr Cogley says it is astonishing that none of the 10 authors of the 2007 IPCC report could spot the error and “misread 2350 as 2035”.

“I do suggest that the glaciological community might consider advising the IPCC about ways to avoid such egregious errors as the 2035 versus 2350 confusion in the future,” says Mr Cogley.

He said the error might also have its origins in a 1999 news report on retreating glaciers in the New Scientist magazine.

The article quoted Syed I Hasnain, the then chairman of the International Commission for Snow and Ice’s (ICSI) Working group on Himalayan glaciology, as saying that most glaciers in the Himalayan region “will vanish within 40 years as a result of global warming”.

Scientists say Himalayan glaciers need more study

When asked how this “error” could have happened, RK Pachauri, the Indian scientist who heads the IPCC, said: “I don’t have anything to add on glaciers.”

The IPCC relied on three documents to arrive at 2035 as the “outer year” for shrinkage of glaciers.

They are: a 2005 World Wide Fund for Nature report on glaciers; a 1996 Unesco document on hydrology; and a 1999 news report in New Scientist.

Incidentally, none of these documents have been reviewed by peer professionals, which is what the IPCC is mandated to be doing.

Murari Lal, a climate expert who was one of the leading authors of the 2007 IPCC report, denied it had its facts wrong about melting Himalayan glaciers.

But he admitted the report relied on non-peer reviewed - or ‘unpublished’ - documents when assessing the status of the glaciers.

‘Alarmist’

Recently India’s Environment Minister Jairam Ramesh released a study on Himalayan glaciers that suggested that they may be not melting as much due to global warming as it is widely feared.

He accused the IPCC of being “alarmist”.

India says the rate of retreat in many glaciers has decreased in recent years

Mr Pachauri dismissed the study as “voodoo science” and said the IPCC was a “sober body” whose work was verified by governments.

But in a joint statement some the world’s leading glaciologists who are also participants to the IPCC have said: “This catalogue of errors in Himalayan glaciology… has caused much confusion that could have been avoided had the norms of scientific publication, including peer review and concentration upon peer-reviewed work, been respected.”

Michael Zemp from the World Glacier Monitoring Service in Zurich also said the IPCC statement on Himalayan glaciers had caused “some major confusion in the media”.

“Under strict consideration of the IPCC rules, it should actually not have been published as it is not based on a sound scientific reference.

“From a present state of knowledge it is not plausible that Himalayan glaciers are disappearing completely within the next few decades. I do not know of any scientific study that does support a complete vanishing of glaciers in the Himalayas within this century.”

Pallava Bagla is science editor for New Delhi Television (NDTV) and author of Destination Moon - India’s quest for Moon, Mars and Beyond.

Aug 30, 2010

Blame Lies With Sun, Not Global Warming

By Julian Morris, Moscow Times

Millions are suffering and thousands have died from flooding in Pakistan and China. An extraordinary heat wave in Russia sparked fires that caused dreadful pollution and wiped out swathes of the wheat crop. Are these weather-related disasters caused by global warming?

In its most recent report, the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change asserts that as the world becomes warmer, “flood magnitude and frequency are likely to increase in most regions.” This seems plausible. A warmer world is also likely to be a wetter world, as more water evaporates from the oceans into the atmosphere. But, although rainstorms put out some of the fires, Russia has a drought.

The UN panel also claims that droughts are more likely in a warmer world - and that they have become more frequent since the 1970s, partly because of reduced precipitation. In fact, the number of droughts reached a low point between the mid-1970s and mid-1980s. Evidence shows that there has been no statistically significant increase in droughts since the 1950s. Given that global temperatures appear to have risen considerably since then, it seems a stretch to blame the Russian drought on global warming.

Underpinning both the floods in Pakistan and China and the drought in Russia is a change in the usual pattern of the jet stream. Each hemisphere has a “polar” jet (seven to 12 kilometers above sea level) and a “subtropical” jet (at 10 to 16 kilometers). In the northern hemisphere, the polar jet pushes cooler air south and induces rain in mid-latitudes, while the subtropical jet pushes warm air north. But in mid-June, a kink appeared at the intersection, causing warm air to remain further north and east than normal and causing more cold air and rain to fall over northern Pakistan and China.

To make matters far worse, this kink in the jet stream was kept in place by a phenomenon called a “blocking event.” This kept the Russian heat wave going for nearly two months and massively exacerbated the precipitation in Pakistan and China.

Such blocking events are rare, and there is no evidence of links with global warming. However, an explanation has been proposed by Professor Mike Lockwood, an astrophysicist at the University of Reading in Britain, who shows in a recent paper that blocking events in the winter are related primarily to solar activity. (Although he cautiously said in an e-mail to me that he “cannot say much (yet) about summer conditions as most of our work to date has been on wintertime, which shows relatively strong solar effects in the Eurasian region").

So the culprit is quite possibly the sun, not human emissions of greenhouse gases.

Comparison of the last four solar cycles, note how cycle 23 was long and our recovery out of it into cycle 24 very slow. This is more like the cycles in the early 1900s and especially the early 1800s.

As for remedies, the current disasters demand a major humanitarian response. Worst affected is Pakistan, where an estimated 6 million people face cholera and other waterborne diseases unless they urgently get potable water. Pakistan’s government responded slowly, making immediate national and international philanthropy even more important.

But what of the longer term? Floods, droughts and other weather disasters have plagued mankind for all of history. But deaths from such natural disasters have fallen by more than 90 percent in the past 100 years despite dramatic population growth. Why? Because higher wealth and better technology enable people better to cope. This is a silver lining to this summer’s natural disasters. See post here.

Julian Morris is a visiting professor at the University of Buckingham and executive director of International Policy Network, London, an independent economic think tank. Richard Lourie will return to this spot in September.

|