Mar 16, 2010

When to Doubt a Scientific ‘Consensus’

By Jay Richards

Anyone who has studied the history of science knows that scientists are not immune to the non-rational dynamics of the herd.

A December 18 Washington Post poll, released on the final day of the ill-fated Copenhagen climate summit, reported “four in ten Americans now saying that they place little or no trust in what scientists have to say about the environment.” Nor is the poll an outlier. Several recent polls have found “climate change” skepticism rising faster than sea levels on Planet Algore (not to be confused with Planet Earth, where sea levels remain relatively stable).

Many of the doubt-inducing climate scientists and their media acolytes attribute this rising skepticism to the stupidity of Americans, philistines unable to appreciate that there is “a scientific consensus on climate change.” One of the benefits of the recent Climategate scandal, which revealed leading climate scientists manipulating data, methods, and peer review to exaggerate the evidence of significant global warming, may be to permanently deflate the rhetorical value of the phrase “scientific consensus.”

Even without the scandal, the very idea of scientific consensus should give us pause. “Consensus,” according to Merriam-Webster, means both “general agreement” and “group solidarity in sentiment and belief.” That pretty much sums up the dilemma. We want to know whether a scientific consensus is based on solid evidence and sound reasoning, or social pressure and groupthink.

Anyone who has studied the history of science knows that scientists are not immune to the non-rational dynamics of the herd. Many false ideas enjoyed consensus opinion at one time. Indeed, the “power of the paradigm” often shapes the thinking of scientists so strongly that they become unable to accurately summarize, let alone evaluate, radical alternatives. Question the paradigm, and some respond with dogmatic fanaticism.

We shouldn’t, of course, forget the other side of the coin. There are always cranks and conspiracy theorists. No matter how well founded a scientific consensus, there’s someone somewhere - easily accessible online - that thinks it’s all hokum. Sometimes these folks turn out to be right. But often, they’re just cranks whose counsel is best disregarded.

So what’s a non-scientist citizen, without the time to study the scientific details, to do? How is the ordinary citizen to distinguish, as Andrew Coyne puts it, “between genuine authority and mere received wisdom? Conversely, how do we tell crankish imperviousness to evidence from legitimate skepticism?” Are we obligated to trust whatever we’re told is based on a scientific consensus unless we can study the science ourselves? When can you doubt a consensus? When should you doubt it?

Your best bet is to look at the process that produced, maintains, and communicates the ostensible consensus. I don’t know of any exhaustive list of signs of suspicion, but, using climate change as a test study, I propose this checklist as a rough-and-ready list of signs for when to consider doubting a scientific “consensus,” whatever the subject. One of these signs may be enough to give pause. If they start to pile up, then it’s wise to be suspicious.

(1) When different claims get bundled together.

Usually, in scientific disputes, there is more than one claim at issue. With global warming, there’s the claim that our planet, on average, is getting warmer. There’s also the claim that human emissions are the main cause of it, that it’s going to be catastrophic, and that we have to transform civilization to deal with it. These are all different assertions with different bases of evidence. Evidence for warming, for instance, isn’t evidence for the cause of that warming. All the polar bears could drown, the glaciers melt, the sea levels rise 20 feet, Newfoundland become a popular place to tan, and that wouldn’t tell us a thing about what caused the warming. This is a matter of logic, not scientific evidence. The effect is not the same as the cause.

There’s a lot more agreement about (1) a modest warming trend since about 1850 than there is about (2) the cause of that trend. There’s even less agreement about (3) the dangers of that trend, or of (4) what to do about it. But these four propositions are frequently bundled together, so that if you doubt one, you’re labeled a climate change “skeptic” or “denier.” That’s just plain intellectually dishonest. When well-established claims are fused with separate, more controversial claims, and the entire conglomeration is covered with the label “consensus,” you have reason for doubt.

(2) When ad hominem attacks against dissenters predominate.

Personal attacks are common in any dispute simply because we’re human. It’s easier to insult than to the follow the thread of an argument. And just because someone makes an ad hominem argument, it doesn’t mean that their conclusion is wrong. But when the personal attacks are the first out of the gate, and when they seem to be growing in intensity and frequency, don your skeptic’s cap and look more closely at the evidence.

When it comes to climate change, ad hominems are all but ubiquitous. They are even smuggled into the way the debate is described. The common label “denier” is one example. Without actually making the argument, this label is supposed to call to mind the assertion of the “great climate scientist” Ellen Goodman: “I would like to say we’re at a point where global warming is impossible to deny. Let’s just say that global warming deniers are now on a par with Holocaust deniers.”

There’s an old legal proverb: If you have the facts on your side, argue the facts. If you have the law on your side, argue the law. If you have neither, attack the witness. When proponents of a scientific consensus lead with an attack on the witness, rather than on the arguments and evidence, be suspicious.

(3) When scientists are pressured to toe the party line.

The famous Lysenko affair in the former Soviet Union is often cited as an example of politics trumping good science. It’s a good example, but it’s often used to imply that such a thing could only happen in a totalitarian culture, that is, when all-powerful elites can control the flow of information. But this misses the almost equally powerful conspiracy of agreement, in which interlocking assumptions and interests combine to give the appearance of objectivity where none exists. For propaganda purposes, this voluntary conspiracy is even more powerful than a literal conspiracy by a dictatorial power, precisely because it looks like people have come to their position by a fair and independent evaluation of the evidence.

Tenure, job promotions, government grants, media accolades, social respectability, Wikipedia entries, and vanity can do what gulags do, only more subtly. Alexis de Tocqueville warned of the power of the majority in American society to erect “formidable barriers around the liberty of opinion; within these barriers an author may write what he pleases, but woe to him if he goes beyond them.” He could have been writing about climate science.

Climategate, and the dishonorable response to its revelations by some official scientific bodies, show that scientists are under pressure to toe the orthodox party line on climate change, and receive many benefits for doing so. That’s another reason for suspicion.

(4) When publishing and peer review in the discipline is cliquish.

Though it has its limits, the peer-review process is meant to provide checks and balances, to weed out bad and misleading work, and to bring some measure of objectivity to scientific research. At its best, it can do that. But when the same few people review and approve each other’s work, you invariably get conflicts of interest. This weakens the case for the supposed consensus, and becomes, instead, another reason to be suspicious. Nerds who follow the climate debate blogosphere have known for years about the cliquish nature of publishing and peer review in climate science (see here, for example).

(5) When dissenting opinions are excluded from the relevant peer-reviewed literature not because of weak evidence or bad arguments but as part of a strategy to marginalize dissent.

Besides mere cliquishness, the “peer review” process in climate science has, in some cases, been consciously, deliberately subverted to prevent dissenting views from being published. Again, denizens of the climate blogosphere have known about these problems for years, but Climategate revealed some of the gory details for the broader public. And again, this gives the lay public a reason to doubt the consensus.

(6) When the actual peer-reviewed literature is misrepresented.

Because of the rhetorical force of the idea of peer review, there’s the temptation to misrepresent it. We’ve been told for years that the peer-reviewed literature is virtually unanimous in its support for human-induced climate change. In Science, Naomi Oreskes even produced a “study” of the relevant literature supposedly showing “The Scientific Consensus on Climate Change.” In fact, there are plenty of dissenting papers in the literature, and this despite mounting evidence that the peer-review deck was stacked against them. The Climategate scandal also underscored this: The climate scientists at the center of the controversy complained in their emails about dissenting papers that managed to survive the peer-review booby traps they helped maintain, and fantasized about torpedoing a respected climate science journal with the temerity to publish a dissenting article.

(7) When consensus is declared hurriedly or before it even exists.

A well-rooted scientific consensus, like a mature oak, usually needs time to emerge. Scientists around the world have to do research, publish articles, read about other research, repeat experiments (where possible), have open debates, make their data and methods available, evaluate arguments, look at the trends, and so forth, before they eventually come to agreement. When scientists rush to declare a consensus, particularly when they claim a consensus that has yet to form, this should give any reasonable person pause.

In 1992, former Vice President Al Gore reassured his listeners, “Only an insignificant fraction of scientists deny the global warming crisis. The time for debate is over. The science is settled.” In the real 1992, however, Gallup “reported that 53% of scientists actively involved in global climate research did not believe global warming had occurred; 30% weren’t sure; and only 17% believed global warming had begun. Even a Greenpeace poll showed 47% of climatologists didn’t think a runaway greenhouse effect was imminent; only 36% thought it possible and a mere 13% thought it probable.” Seventeen years later, in 2009, Gore apparently determined that he needed to revise his own revisionist history, asserting that the scientific debate over human-induced climate change had raged until as late as 1999, but now there was true consensus. Of course, 2009 is when Climategate broke, reminding us that what had smelled funny before might indeed be a little rotten.

(8) When the subject matter seems, by its nature, to resist consensus.

It makes sense that chemists over time may come to unanimous conclusions about the results of some chemical reaction, since they can replicate the results over and over in their own labs. They can see the connection between the conditions and its effects. It’s easily testable. But many of the things under consideration in climate science are not like that. The evidence is scattered and hard to keep track of; it’s often indirect, imbedded in history and requiring all sorts of assumptions. You can’t rerun past climate to test it, as you can with chemistry experiments. And the headline-grabbing conclusions of climate scientists are based on complex computer models that climate scientists themselves concede do not accurately model the underlying reality, and receive their input, not from the data, but from the scientists interpreting the data. This isn’t the sort of scientific endeavor on which a wide, well-established consensus is easily rendered. In fact, if there really were a consensus on all the various claims surrounding climate science, that would be really suspicious. A fortiori, the claim of consensus is a bit suspicious as well.

(9) When “scientists say” or “science says” is a common locution.

In Newsweek’s April 28, 1975, issue, science editor Peter Gwynne claimed that “scientists are almost unanimous” that global cooling was underway. Now we are told, “Scientists say global warming will lead to the extinction of plant and animal species, the flooding of coastal areas from rising seas, more extreme weather, more drought and diseases spreading more widely.” “Scientists say” is hopelessly ambiguous. Your mind should immediately wonder: “Which ones?”

Other times this vague company of scientists becomes “SCIENCE,” as when we’re told “what science says is required to avoid catastrophic climate change.” “Science says” is an inherently weasely claim. “Science,” after all, is an abstract noun. It can’t say anything. Whenever you see that locution used to imply a consensus, it should trigger your baloney detector.

(10) When it is being used to justify dramatic political or economic policies.

Imagine hundreds of world leaders and nongovernmental organizations, science groups, and United Nations functionaries gathered for a meeting heralded as the most important conference since World War II, in which “the future of the world’is being decided."” These officials seem to agree that institutions of “global governance” need to be established to reorder the world economy and massively restrict energy resources. Large numbers of them applaud wildly when socialist dictators denounce capitalism. Strange philosophical and metaphysical activism surrounds the gathering. And we are told by our president that all of this is based, not on fiction, but on science - that is, a scientific consensus that human activities, particularly greenhouse gas emissions, are leading to catastrophic climate change.

We don’t have to imagine that scenario, of course. It happened in Copenhagen, in December. Now, none of this disproves the hypothesis of catastrophic, human induced climate change. But it does describe an atmosphere that would be highly conducive to misrepresentation. And at the very least, when policy consequences, which claim to be based on science, are so profound, the evidence ought to be rock solid. “Extraordinary claims,” the late Carl Sagan often said, “require extraordinary evidence.” When the megaphones of consensus insist that there’s no time, that we have to move, MOVE, MOVE!, you have a right to be suspicious.

(11) When the “consensus” is maintained by an army of water-carrying journalists who defend it with uncritical and partisan zeal, and seem intent on helping certain scientists with their messaging rather than reporting on the field as objectively as possible.

Do I really need to elaborate on this point?

(12) When we keep being told that there’s a scientific consensus.

A scientific consensus should be based on scientific evidence. But a consensus is not itself the evidence. And with really well-established scientific theories, you never hear about consensus. No one talks about the consensus that the planets orbit the sun, that the hydrogen molecule is lighter than the oxygen molecule, that salt is sodium chloride, that light travels about 186,000 miles per second in a vacuum, that bacteria sometimes cause illness, or that blood carries oxygen to our organs. The very fact that we hear so much about a consensus on catastrophic, human-induced climate change is perhaps enough by itself to justify suspicion.

To adapt that old legal aphorism, when you’ve got decisive scientific evidence on your side, you argue the evidence. When you’ve got great arguments, you make the arguments. When you don’t have decisive evidence or great arguments, you claim consensus. Download story here.

Jay Richards frequently writes for the Enterprise Blog and is a contributing editor of THE AMERICAN.

Mar 14, 2010

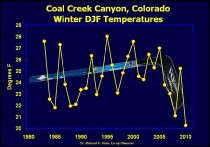

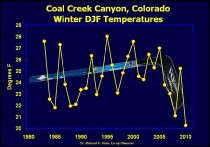

Coal Creek Canyon, Colorado; another chilly month and winter

By Richard Keen, Ph.D. Canyon Creek, CO

At 19.4 degrees, February 2010 was the second coldest February of record here (since 1983), missing February 1989’s 18.2 by just over one degree.

• There were three less-than-impressive daily record lows in the 0 to -3 range. But there were other more impressive records:

• 17 consecutive days with daily max temperatures at or below 32F tied a record set in December 1983.

• 22 days with daily max temperatures at or below 32F tied the January 1988 record (and exceeds it if you consider that February is a short month).

• The monthly maximum of 40F tied December 1983 for the lowest monthly max on record.

And the biggie record....

• The three-month winter average (December-February) of 20.2F is, by almost one degree, the coldest winter on record here (28 winters). History of the past five winters: 2005-06 - coldest winter since 1997-98. 2006-07 - coldest winter since 1992-93; last snow drift melted July 6. 2007-08 - coldest winter on record, beat 83-84 by 0.7 degrees. 2008-09 - near normal. 2009-10 - coldest winter, beat 07-08 by 0.9 degrees.

For comparison here’s my ten coldest months: Dec-09 16.5 Dec-83 17.2 Feb-89 18.2 Dec-90 18.5 Jan-85 18.7 Jan-07 18.8 Jan-88 19.1 Dec-07 19.4 Feb-10 19.4 Jan-08 19.7 Note that five of the cold months occurred during 1983-1990 (8 years), None during 1991-2005 (15 years), And five during 2007-2010 (4 years). The season’s snow stands at 140.5 inches, the fourth greatest end-of-February total (after 2007, 1987, and 1998). February 28th is the normal mid-point of our snow season, with, on average, 100 inches by February and another 100 inches in March and the other “spring” months (including June).

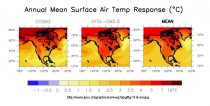

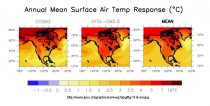

A series of cold winters at one location may not seem too important, but the story is the same across much of the country (and both hemispheres of the planet). On an annual basis, Coal Creek correlates with the entire state of Colorado With a correlation R = 0.95. The IPCC projects Colorado, the Rocky Mountains, and the Intermountain West to have the greatest warming in the “lower 48” states - about 4C, or 7F, over this century (see IPCC fig-11-8-3). According to the IPCC models, greenhouse gas warming should be greatest over continental interiors and in the middle troposphere, so Coal Creek Canyon is an ideal “global warming” monitoring site. Annual and winter temperatures here in the Rockies show that the new century’s projected warming is off to a shaky start. Here is a graph of winter temperatures since 1983 with various trend lines and curves fit to the data. The linear trend has winter temperatures cooling by 1.1F per century, but with a R-squared of 0.0021 this trend line is hardly significant. The 2nd- and 3rd-order trend line fits have higher correlations and more impressive downturns in recent years, and the five-year running mean also shows a recent decline. However, the best fit is with my favorite non-linear trend line shown in the second graph.

Enlarged here.

Enlarged here.

Enlarged here.

Mar 14, 2010

Six myths about “deniers”

By Bill DiPuccio

Global warming “deniers”: myth-conceptions abound

They’ve been compared to “flat earthers” and even “Holocaust deniers”. And, as the recent “Climategate” email scandal reveals, they have been blacklisted in certain professional circles. Scientists who disagree with the current consensus on Anthropogenic Global Warming (AGW) are dismissed by some colleagues and politicians as ignorant and irrelevant. Though there are certainly cranks out there who lend credence to this stereotype, not everyone who rejects the idea that global warming is a planetary crisis brought about by burning fossil fuels deserves to be vilified.

There are numerous myths surrounding those who are wrongly labeled “deniers” Most of them can be distilled into six basic accusations:

1. “Deniers” believe the climate has not warmed.

No one questions that there has been a slight, but unmistakable increase in global temperature since the end of the “Little Ice Age” in the early nineteenth century. Global average surface temperature has risen approximately 0.9C since 1850. But not all scientists attribute this change to the human addition of CO2 and other greenhouse gases to the air. Those who oppose the prevailing view on AGW point out that since temperatures began to increase well before CO2 levels were considered significant (c. 1940), a considerable part of this warming is due to natural variations in the climate. Such variations in the past have brought about abrupt climate changes with large swings in temperature.

Numerous articles have appeared in scientific journals over the last several years documenting a warm bias in official temperature measurements. This bias, which may account for up to half of the reported warming, is due largely to changes in land cover - especially the geographic expansion of cities which creates “urban heat islands.” An ongoing survey of over 1000 climate reporting stations in the United States, shows that 69% are poorly sited resulting in errors of 2C to 5C or more (www.surfacestations.org). Surface data has also been impaired from station dropout. Over two-thirds of the world’s stations were dropped from the climate network around 1990. Most of them were colder, high latitude and rural stations.

2. “Deniers” are not real scientists.

Some of the world’s foremost atmospheric scientists, physicists, astronomers, and geologists disagree with the current consensus on anthropogenic global warming. These include Richard Lindzen (Massachusetts Institute of Technology), Roger Pielke Sr. (University of Colorado), Roy Spencer and John Christy (University of Alabama), Willie Soon (Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics), Robert Carter (James Cook University, Australia), Fred Singer (University of Virginia), Will Happer (Princeton University), and Nils-Axel Morner (Stockholm University). In addition to these, there are hundreds of credentialed scientists at universities around the world who reject the hypothesis that CO2 induced warming dominates changes in earth’s climate system.

Though science is not based on authority, the inclusion of such high profile scientists should raise red flags when advocates claim that the “science is settled.”

3. “Deniers” are a tiny minority of scientists.

“Nay-sayers” are overshadowed by a vast majority of learned scientific bodies that support the consensus. But most scientific organizations, such as the American Meteorological Society, the American Physical Society, and the National Academies of Science, do not poll their members. Decisions and position statements are made by a small group of officials at the top of the organization. This has created sharp unrest within some professional societies.

The American Meteorological Society is a case in point. A recent survey of AMS broadcast meteorologists revealed that 50% of the respondents disagreed, and only 24% agreed, with the statement that, “Most of the warming since 1950 is very likely human-induced.” When asked if, “Global climate models are reliable in their projections for a warming of the planet,” only 19% agreed, while 62% disagreed (Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, Oct. 2009).

As the number of those who oppose the consensus grows, it appears that the “deniers” are not a tiny minority as is often claimed.

4. “Deniers” are anti-environmental shills of Big Oil.

Only a small number of scientists who challenge the current consensus have direct ties to the fossil fuel industry. Most are funded by university departments, governments, or private institutions. Many receive no funding at all. Unfortunately, no amount of evidence can unseat the deeply held belief among some, that opposition to the AGW hypothesis is part of a conspiracy funded by big oil. The underlying fear is that any scientific research subsidized by big corporate money will be compromised.

But the blade cuts both ways. Climate research among those who espouse the prevailing view is supported by billions of dollars from government grants and green industries that have a vested interest in global warming. Why should research conducted or funded by environmental organizations and green energy be regarded as more reliable? Whether science is bought and sold by deep pockets, or made subservient to a political or philosophical ideology, the result is the same: Truth is compromised.

5. “Deniers” think CO2 is irrelevant.

The issue is not whether CO2 is irrelevant, but, rather, how relevant is it? The U.N.’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) maintains that CO2 induced warming dominates the climate system. They project that increasing emissions will result in a 2C to 6C rise in global average temperature by the year 2100.

This has been widely misunderstood by the public to mean that energy absorbed and reradiated by atmospheric CO2 is the direct cause of the warming. In reality, the IPCC claims that CO2, acting alone, will result in only a 1.2C rise in temperature. The rest depends on whether the climate amplifies (positive feedback) or diminishes (negative feedback) CO2 forcing.

This is where the real dispute lies. Climate “sensitivity” is based on numerous interactions that are poorly understood. Scientists who disagree with the IPCC’s conclusions are not contesting the fact that CO2 can cause atmospheric warming (0.3C according to more conservative estimates). They disagree with the science behind the water vapor feedback mechanisms that are said to amplify this warming on a global scale. The complex and chaotic processes underlying these mechanisms, especially as they relate to cloud formation and precipitation, exceed the limits of our knowledge. As a result, climate feedback is not simply the product of numerical calculations ("straightforward physics") as is often supposed, but depends extensively on large scale estimates (parameterizations) by computer modelers.

“Deniers” demand empirical proof and are quick to point out that the water vapor feedback hypothesis is poorly supported by hard evidence, and even contradicted by the absence of warming in both the oceans and the atmosphere over the last several years. In fact, some scientists (Lindzen, Spencer, etc.) theorize that water vapor and cloud cover act like a thermostat (negative feedback) to maintain the earth’s temperature in approximate equilibrium.

6. “Deniers” believe humans have no impact on climate.

Scientists who challenge the status quo point out that we live in regional and local climates with vast differences in temperature and precipitation -differences that far outweigh changing global averages. Given these differences, the idea of “average global temperature” seems rather meaningless. More importantly, the human impact on climate is far greater at regional and local scales than it is on a global scale. These impacts include land use and land cover changes (e.g., deforestation, agriculture, urbanization) and aerosol pollution (e.g., soot, sulfur, reactive nitrogen, dust). Any one of these modifications can significantly alter temperature, evaporation, cloud cover, precipitation, and wind over a region - and perhaps beyond.

Though the global surface area of agricultural land alone is greater than the size of South America, the IPCC has largely ignored the influence of land cover and aerosols on regional climates. Moreover, climate models have shown no skill in projecting regional climate changes decades in advance.

But a wave of new research is forcing scientists to reevaluate the impact of these factors. Some have already concluded that the effect of CO2 has been overstated while regional changes in land use and aerosol pollution have been grossly underestimated. One recent study of U.S. climate has concluded that land use changes alone may account for 50% of the warming since 1950 (International Journal of Climatology, August, 2009).

“Deniers” vs. the “Consensus”

Though “deniers” unanimously agree that CO2 is not the main driver of climate change, they represent a diversity of scientific viewpoints on issues of climate change, green energy, and the environment - perhaps a greater diversity than scientists who are in lock-step with the consensus. The Climategate scandal has exposed a concerted effort on the part of some IPCC scientists to enforce this consensus by denying access to crucial data and marginalizing anyone who questions the scientific basis of their conclusions. Stealthy tactics like this undermine scientific progress which depends on a robust exchange of information and ideas.

Skepticism is at the heart of the scientific method. So it is ironic that those who have challenged the prevailing orthodoxy are regarded as outcasts. Fortunately, science is not settled by popular vote or authority, but by empirical evidence. History has not always vindicated the majority view or justified the assumed authority of “official science.” Consequently, it may be the “deniers”, rather than their opponents, who have the last word on global warming.

Bill DiPuccio served as a weather forecaster and lab instructor for the U.S. Navy, and a Meteorological Radiosonde Technician for the National Weather Service. More recently, he was the head of the science department for Orthodox Christian Schools of Northeast Ohio.

------------------------------

New book “Climatism” by Steve Goreham, a “must read’

There are many excellent books for your consideration in the Icecap Amazon Book section on the left column. The latest addition is the book Climatism by Steve Goreham. Here are some reviewer’s comments on the book:

“This is a serious book that carefully examines the issues that have been used to create the current climate change - global warming crisis...I endorse Climatism! for its easy-to-read, well-illustrated presentation of complex science” John Coleman, Meteorologist

“...a very coherent and convincing book on perhaps the most crucial social, political and economic issue of the 21st century.” Professor Michael J. Economides, University of Houston

“If you care about the 21st century society, you must read this book”. Jay Lehr, PhD., Science Director, the Heartland Institute

Mar 12, 2010

Climate Progress Makes Stuff Up

By Chris Horner, Planet Gore

So much fun! On the heels of this game-changing revelation in an e-mail I received under the Freedom of Information Act, lamenting that the NASA GISS data are - in the eyes of NASA GISS scientists themselves - less credible than the Climategate CRU data. As a quick reminder for those who have been away on interstellar travel for the past four months - or just relying on broadcast networks and the NYT and Washington Post for your news - that is the data which for all legal and scientific purposes does not exist (they lost it/destroyed it/dog ate it). As you’ll see, that is now of even greater significance than it was days ago.

The latest jolly has just come from taking a quick spin around Al Gore’s interwebs to see what NASA might have said about Climategate, and to review in the wake of that huge embarrassment the alarmist walk-back on the importance of CRU, which one establishment pressure group dismissed as merely “one of four organizations worldwide that have independently compiled thermometer measurements of local temperatures from around the world to reconstruct the history of average global surface temperature.” That spin from Pew is not quite accurate, but seems to have been thrown out there to stave off reality. The truth as we now know it is that NASA admits its data is not independent at all, but thoroughly dependent upon CRU’s - which, we have established, doesn’t exist. I’ll let the kids at Climate Progress do the math from there.

But better, in the wake of Climategate this post (screen shot it like I did, it won’t go un-edited for long!) we have the dangerously unhinged Team Soros crowd at Climate Progress contemporaneously shouting anything they could make up - including testimonials to NASA’s unreliable/fabricated/non-existent temperature record like “NASA’s dataset, which is superior to the Met Office/Hadley/CRU dataset.”

Chuckle. Of course it is, dear. Except that even NASA’s own activists don’t dare make that one up.

Now in the hole, CP would dig deeper: “There’s little doubt that the GISS dataset better matches reality than Hadley/ CRU dataset.” If that turned out to be true it would be for no reason other than dumb luck since, again, NASA created its global temperature data set by taking CRU claims and adding NCDC’s for the U.S. As NASA began mewling after getting caught in 2007 sexing up U.S. temperatures, well, the U.S. is only 2 percent of the earth’s surface. Meaning NASA’s data set is 98 percent made-up, even if you ignore NCDC’s myriad problems of using temps from thermometers moved to airport runways, next to barbecue grills, and the like.

Hansen went public to dismiss Climategate with a response - helpfully linked to by the gang at Climate Progress as proof there’s nothing to see there - in which he describes how his office arrives at their data set. Oddly, he fails to admit that this process has depended on CRU data for global temperatures.

He does say, “Although the three input data streams that we use are publicly available from the organizations that produce them, we began preserving the complete input data sets each month in April 2008.” Ooh, all the way back then? He does not say that this occurred when they realized during the kerfuffle over what Steven McIntyre discovered about GISS in August 2007 that they, too, did not keep their original data which they they then manipulate to arrive at their claims. So he also left out that - as admitted in another e-mail I have - a Hansen colleague was relieved that he was able to obtain one of the needed, discarded data sets from a Brazilian journalist. Really. Thanks again, FOIA.

In the same post Hansen opens with a rather pathetic (given the regular, long-running tactics of his team) paean to the sorry state of affairs to which we have devolved such that people feel threatened for their views and speech. This must have gravely disappointed the nuts over at Climate Progress. So, two words Jim: Food-taster. I’d say car-starter, but you probably drive a hybrid, and they wouldn’t blow one of those up.

See post here.

-------------------------

Those Climate Pugilists

By Paul Chesser, American Spectator

Pity the poor Climategaters. The staid were played. Gentlepersons were violated. And the billion-dollar global warming science complex can’t compete with spunky skeptics.

Those are some of the complaints registered in newly disclosed emails among members of the National Academy of Sciences, whose messages were mysteriously made public last week via the Washington Times. Some call it Climategate II; Whinergate is more apropos.

Among their electronically-sent lamentations:

• “Most of our colleagues don’t seem to grasp that we’re not in a gentlepersons’ debate, we’re in a street fight against well-funded, merciless enemies who play by entirely different rules,” said Paul “Nostradamus” Ehrlich, a Stanford University biologist.

• “This was an outpouring of angry frustration on the part of normally very staid scientists who said, ‘God, can’t we have a civil dialogue here and discuss the truth without spinning everything,’” said Stephen H. Schneider, a Stanford professor and senior fellow at the Woods Institute for the Environment.

• “They’re not going to win short-term battles playing the game against big-monied interests because they can’t beat them,” Schneider, in a phone interview, talking about alleged competition with energy company funding of skeptics.

Wow—Schneider, who in a November interview with the New Republic announced, “I am an activist,” claims that he spurns spin. Just check the rest of his rhetoric from a few months ago:

• “The models have done really well on temperature over a long time period so we trust that.”

• “The IPCC says, ‘One to five degrees warming [by 2100]’ for example. That is an expert judgment; it’s subjective, but built on objective modeling and data.”

• “I don’t have aggregate dollars as my moral principle—I look at who’s responsible.”

Yes, the models were so good they missed the non-warming of the last 15 years—probably thanks to the Climategaters’ unassailable data. And like most alarmists who speak from the global warming script, Schneider looks only at opponents’ aggregate cash while linking it to their immoral stands against “science.” Meanwhile we are to believe his objective team of activists is untainted by the many more billions of dollars that flow to their research institutes and eco-minded nonprofits.

And undoubtedly it was principled, trustworthy, objective modeling and data that informed Schneider’s most recent (November) book: Science as a Contact Sport. As the inside jacket explains, “Schneider’s efforts have helped bring about important measures to safeguard our planet, but there’s still more to be done to get them implemented.” That “S” on his chest doesn’t represent his surname.

Schneider is so measured and balanced in his “sound science” advocacy, that in the new “Whinergate” emails he urges his NAS colleagues to admit Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory climate scientist Ben Santer to their exclusive society. “Can we please get that finally done next year!!” he doubly exclaimed.

You might recall the even-tempered Santer as the bloke from the original Climategate scandal that arose out of Britain’s University of East Anglia, who told Climatic Research Unit director Phil Jones that he’d be tempted—“very tempted”—to “beat the crap out of” skeptical climatologist Pat Michaels. Santer, as lead author of the UN IPCC’s 1995 second assessment report on the science, also admitted deleting statements that denied a human influence on climate change. This kind of behavior apparently has been established as common scientific procedure by “Contact Sport” practitioners—better known as “The Fight Club” within the NAS.

No wonder why, as the Washington Times reported last week, this discredited bunch wants to punch back at skeptics. The Whinergate emails disclosed that one of their strategies of persuasion is to chip in and purchase a back-page ad in the New York Times that would challenge their critics. This presumably would get their mini-choir of fellow elitists singing from their hymnal—but would totally miss the unconverted. Next up—a double-page glossy spread in Audubon! And they wonder why their message isn’t getting through.

Rock-solid science is built with a firm foundation of verifiable and repeatable tests, with trustworthy facts and figures as their sources. The Whinergate scientists employed fudged data and their personal agendas to belligerently promote a fabricated cause, amplified by their similarly unpopular anti-capitalist cohorts and ever-expanding government. Now they profess surprise at the growing resistance to their mission.

They still have not learned that all the money, media and muscle at their disposal have not produced sound science, or a victory. Tactics may provide a temporary advantage, but facts usually win, even though sometimes it takes a while. See post here.

Mar 11, 2010

Loony Erlich is the ideal spokesman for the AGW movement

By Paul Erlich

The question of the day is how Paul Erlich, doomsayer deluxe, could still have a job never mind pen an editorial for Nature. In today’s world it doesn’t matter if you were ever right only that you are in agreement in Dick Lindzen’s words with “the sensibilities of the east and west coast” elitists. See this story on some of his former prognostications about the future of humanity including only 20 million people would still be alive in the U.S by 2000 because of pesticides. Recently he led the attack on skeptics in the New York Times “Most of our colleagues don’t seem to grasp that we’re not in a gentlepersons’ debate, we’re in a street fight against well-funded, merciless enemies who play by entirely different rules,” Paul R. Ehrlich, a Stanford University researcher, said in one of the e-mails.

Ehrlich started his academic career as an entomologist, an expert on Lepidoptera - butterflies. Following are excerpts from that Nature editorial.

The integrity of climate research has taken a very public battering in recent months. Scientists must now emphasize the science, while acknowledging that they are in a street fight.

Climate scientists are on the defensive, knocked off balance by a re-energized community of global-warming deniers who, by dominating the media agenda, are sowing doubts about the fundamental science. Most researchers find themselves completely out of their league in this kind of battle because it’s only superficially about the science. The real goal is to stoke the angry fires of talk radio, cable news, the blogosphere and the like, all of which feed off of contrarian story lines and seldom make the time to assess facts and weigh evidence. Civility, honesty, fact and perspective are irrelevant.

Worse, the onslaught seems to be working: some polls in the United States and abroad suggest that it is eroding public confidence in climate science at a time when the fundamental understanding of the climate system, although far from complete, is stronger than ever. Ecologist Paul Ehrlich at Stanford University in California says that his climate colleagues are at a loss about how to counter the attacks. “Everyone is scared shitless, but they don’t know what to do,” he says.

Scientists must not be so naive as to assume that the data speak for themselves. Researchers should not despair. For all the public’s confusion about climate science, polls consistently show that people trust scientists more than almost anybody else to give honest advice. Yes, scientists’ reputations have taken a hit thanks to headlines about the leaked climate e-mails at the University of East Anglia (UEA), UK, and an acknowledged mistake about the retreat of Himalayan glaciers in a recent report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). But these wounds are not necessarily fatal.

To make sure they are not, scientists must acknowledge that they are in a street fight, and that their relationship with the media really matters. Anything strategic that can be done on that front would be useful, be it media training for scientists or building links with credible public-relations firms. In this light, there are lessons to be learned from the current spate of controversies. For example, the IPCC error was originally caught by scientists, not sceptics. Had it been promptly corrected and openly explained to the media, in full context with the underlying science, the story would have lasted days, not weeks. The IPCC must establish a formal process for rapidly investigating and, when necessary, correcting such errors.

The unguarded exchanges in the UEA e-mails speak for themselves. Although the scientific process seems to have worked as it should have in the end, the e-mails do raise concerns about scientific behaviour and must be fully investigated. Public trust in scientists is based not just on their competence, but also on their perceived objectivity and openness. Researchers would be wise to remember this at all times, even when casually e-mailing colleagues.

US scientists recently learned this lesson yet again when a private e-mail discussion between leading climate researchers on how to deal with sceptics went live on conservative websites, leading to charges that the scientific elite was conspiring to silence climate sceptics (see page 149). The discussion was spurred by a report last month from Senator James Inhofe (Republican, Oklahoma), the leading climate sceptic in the US Congress, who labelled several respected climate scientists as potential criminals - nonsense that was hardly a surprise considering the source. Some scientists have responded by calling for a unified public rebuttal to Inhofe, and they have a point. As a member of the minority party, Inhofe is powerless for now, but that may one day change. In the meantime, Inhofe’s report is only as effective as the attention it receives, which is why scientists need to be careful about how they engage such critics.

The core science supporting anthropogenic global warming has not changed. This needs to be stated again and again, in as many contexts as possible. Scientists must not be so naive as to assume that the data speak for themselves. Nor should governments. Scientific agencies in the United States, Europe and beyond have been oddly silent over the recent controversies. In testimony on Capitol Hill last month, the head of the US Environmental Protection Agency, Lisa Jackson, offered at best a weak defence of the science while seeming to distance her agency’s deliberations from a tarnished IPCC. Officials of her stature should be ready to defend scientists where necessary, and at all times give a credible explanation of the science.

These challenges are not new, and they won’t go away any time soon. Even before the present controversies, climate legislation had hit a wall in the US Senate, where the poorly informed public debate often leaves one wondering whether science has any role at all. The IPCC’s fourth assessment report had huge influence leading up to the climate conference in Copenhagen last year, but it was always clear that policy-makers were reluctant to commit to serious reductions in greenhouse-gas emissions. Scientists can’t do much about that, but they can and must continue to inform policy-makers about the underlying science and the potential consequences of policy decisions - while making sure they are not bested in the court of public opinion.

|