Steven Novella, Neurologicablog

One of the strengths of the skeptical movement, as an intellectual community, is that we wrangle with important issues regarding the relationship between science and what people do and should accept as probably true. We deal with not only specific issues, but the bigger question of process. For example, how much weight should an individual give to any specific scientific consensus, and is this just an argument from authority?

This question has recently become central to the debate over climate change, one of those few scientific debates that fractures the skeptical community. We are fairly united when it comes to the question of ghosts, Bigfoot, and UFOs. But when certain topics come up, like climate change, there is disagreement over the meaning of consensus, what the consensus is, and the very definition of “skeptic”.

Consensus vs Authority

Deferring to the scientific consensus on a given topic is not the same thing as making an argument from authority, a logical fallacy to be avoided. The argument from authority essentially follows the pattern of concluding that a claim is true because it is being made by a person of some authority (scientific or otherwise). Most of us spend our childhood committing this logical fallacy, the right answer is whatever an adult says it is, or the teacher, or whatever the news reports “scientists” are saying.

As we mature and grow in personal knowledge we eventually cross a threshold where we feel confident relying on our own judgment, even to the point of rejecting authority. This seems to be instinctive for teenagers, and of course the rejection of authority simply because it is authority is an overcompensation. Ideally, as adults, we reach an equilibrium where we listen to authority, but understand its limits, and do not use authority as a replacement for independent thought.

As skeptics we have collectively tried to develop a nuanced and sophisticated approach to scientific authority, and many excellent articles have been written on this topic. Since we advocate rigorous and robust scientific methodology as the best way of understanding nature, we trust this process to some degree. We understand there can be fraud or sloppy studies, but generally if the research of others is all pointing toward one answer, we trust that research and its conclusions.

But science is complex, and few people can master more than a fairly narrow range of scientific expertise. And so outside our area of expertise (which is all of science for non-scientists) the best approach to take, in my opinion, is a hybrid approach, first, try to understand what is the consensus of scientific opinion. This is a good starting point, what do scientists believe, what do they agree on, and where is there legitimate controversy? How sure are they of their conclusions, and how strong is the consensus on any particular question?

But also, those interested in science will want to understand the evidence directly and how it relates to the consensus. But at the same time it must be recognized that a non-expert understanding of the evidence is a mere shadow of expert understanding. For example, I have read many articles about Archaeopteryx, a transitional species between theropod dinosaurs and modern birds. I can rattle off some of the anatomical details that mark Archaeopteryx as transitional, the presence of teeth and a long bony tail, for example. But there are details of anatomy that I cannot hope to appreciate, that require months or years of study and apprenticeship, and experience actually examining and describing fossils, of immersing oneself in the literature at the finest level of technical detail. And so ultimately I am trusting experts to interpret the fossil for me, not to mention to reconstruct the bones in the first place. I can only try to understand it on the deepest level I can.

What I conclude from this is that it is extreme hubris to substitute one’s frail non-expert assessment of a detailed scientific discipline for the consensus of opinion of scientific experts.

But there is still more complexity to this issue. First, the consensus of opinion is not always right, it is just usually right. So one can always think that for any particular question this is one of those rare times when the consensus got it wrong. Also, there is almost always a minority opinion among experts, the outlier who is an expert but who constructs the evidence in a different way. So the non-expert can always tell themselves that a particular scientist who is an expert agrees with their opinion. This is not very reassuring, because such minority opinions are in the minority for a reason, and generally turn out to be false. (Although they serve a very useful function in the process of debate and analysis that is science.)

Further, I would argue that there are skill sets that apply, at least to some degree, to just about any science. There is knowledge of scientific methodology and the pitfalls of pathological science. So it is possible to recognize pathological science even in a discipline in which one is not an expert. But even still such out-of-field critiques should be undertaken with extreme caution. The question is, is the criticism dependent upon a detailed technical knowledge of the field, or a recognition that some underlying assumptions and methods are wrong. Even in the latter case, it is good practice to check oneself with an actual expert, to make sure you are not missing something.

I offer as an example the recent criticism of evolutionary theory by non-biologists Fodor and Piattelli-Palmarini. P.Z. Myers explains very well where they went wrong, they make all the mistakes of not respecting a consensus or the limits of their technical knowledge outside their area of expertise.

Climate Change

Getting back to climate change, all of the complexities of assessing consensus are in play. Generally, non-experts tend to accept or reject anthropogenic climate change based upon their politics and world-view. That is a strong indication that most people are not assessing the science objectively, but are simply fitting the science to their ideology.

Don Braman, a faculty member of George Washington University and part of The Cultural Cognition Project, is quoted as saying:

“People tend to conform their factual beliefs to ones that are consistent with their cultural outlook, their world view,” Braman says.

The Cultural Cognition Project has conducted several experiments to back that up.

In the same report, Robert Kennedy Jr. is quoted as saying:

“Ninety-eight percent of the research climatologists in the world say that global warming is real, that its impacts are going to be catastrophic,” he argued. “There are 2 percent who disagree with that. I have a choice of believing the 98 percent or the 2 percent.”

That is a basic statement of acceptance of the scientific consensus. But Robert Kennedy is not always a fan of the scientific consensus, for example he rejects the scientific consensus on vaccines, choosing to believe that the consensus is a deliberate fraud (exactly what global warming dissidents say about the climate change consensus). This makes Robert Kennedy a hypocrite, he accepts the scientific consensus and cites its authority when it suits his politics, and then blithely rejects it (spinning absurd conspiracy theories that would make Jesse Ventura blush) when it is inconvenient to his politics.

But Kennedy is not alone, this seems to be what most people do most of the time. In fact I would argue that we need to be especially suspicious of our scientific opinions on controversial topics when they conform to our personal ideology (whether political, social, or religious). That is when we need to step back and ask hard questions that challenge the views we want to hold. We also need to make sure that our process is consistent across questions, are we citing the scientific consensus on one issue and rejecting it on another? Are we citing conflicts of interest for researchers whose conclusions we don’t like, and ignoring them for researchers whose conclusions confirm our beliefs?

Skeptics

Being a skeptic is partly about wringing our hands and closely examining these very question, especially as they pertain to our own beliefs. The question of scientific consensus is complicated, and my views on the topic have evolved over the years as I have discussed the issue with my fellow skeptics and tried to apply it to specific issues. It is an issue worth examining closely.

A new study by NERA Economic Consulting and commissioned by the National Association of Manufacturers (NAM) reveals that a new ozone regulation from the Obama Administration could cost $270 billion per year and place millions of jobs at risk. This would be the most expensive regulation ever imposed on the American public.

In December 2014, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) will likely propose a more stringent National Ambient Air Quality Standard (NAAQS) for ground-level ozone, lowering the existing standard from 75 parts per billion (ppb) to as low as 60 ppb.

To date, the EPA has only identified one-third of the controls needed to meet the possible new standard; the other two-thirds must come from controls the EPA has not identified. NERA’s report looked at the types of controls needed to fill that unknown gap and found that they will be much more expensive. This is because they are likely to include the shutdown, scrappage or modification of power plants, factories, heavy-duty vehicles, off-road vehicles and even passenger cars. As a result, the negative impacts of a new NAAQS for ground-level ozone will reverberate throughout the entire economy. Total compliance costs could measure in the trillions of dollars, and barriers to energy production could severely limit economic growth and hinder the nation’s manufacturing comeback.

The study found that a stricter new ozone regulation could:

Reduce U.S. GDP by $270 billion per year and $3.4 trillion from 2017 to 2040;

Result in 2.9 million fewer job equivalents per year on average through 2040;

Cost the average U.S. household $1,570 per year in the form of lost consumption; and

Increase natural gas and electricity costs for manufacturers and households across the country.

In brief, such a rule could place tremendous cost and compliance burdens on states and their resources. The study also found that the EPA has yet to adequately address two critical issues related to revising the existing ozone standard:

There are major gaps in data on compliance technologies and their costs in the EPA’s most recent analysis. Only about one-third of the emissions reductions necessary to get to the low end of the standards the EPA is contemplating can be achieved with known controls.

This means that the agency has yet to identify what, if any, controls are available to achieve the majority of the necessary emissions reductions and adequately address what those controls might cost.

New oil and natural gas production could be significantly restricted in parts of the country classified as “nonattainment” areas, limiting supplies of critical energy resources and potentially driving up costs for manufacturers and households. The EPA has yet to address the potential impacts tighter ozone standards could have on energy production and costs.

The study considered the potential implications of energy curtailment by estimating the economic impacts if limits to new natural gas development were added to compliance costs. The study found that restrictions to new natural gas production from tighter ozone regulations, in combination with the costs to reduce emissions, could:

Reduce the present value of GDP by nearly $4.5 trillion through 2040, result in a loss of 4.3 million job equivalents per year and cost households $2,040 annually; and Increase industrial natural gas costs by an average of 52 percent and electricity costs by an average of 23 percent over what they would be if the ozone standard was unchanged.

Such cost impacts could crush the manufacturing comeback by removing our nation’s energy advantage. The NAM urges the EPA and the Obama Administration to abandon plans to revise and tighten the NAAQS for ground-level ozone. The current standard of 75 ppb the most stringent standard ever has not even been implemented yet, while emissions are as low as they have been in decades, and air quality continues to improve.

Enlarged

The NAM makes this statement based on compliance costs measured by NERA Economic Consulting and White House Office of Management and Budget reports to Congress assessing the costs of regulations back to 1988.

By Joseph D’Aleo, CCM

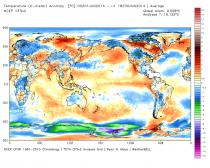

Last month was the hottest June since record keeping began in 1880, the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) said Monday. It marked the third month in a row that global temperature reached a record high. According to the NOAA data, April and May were also global record-breakers. The combined average temperature over global land and ocean surfaces for June 2014 was record high for the month at 16.22 degrees Celsius, or 0.72 degree Celsius above the 20th century average of 15.5 degrees Celsius,’ the NOAA said in its monthly climate report. “This surpasses the previous record, set in 2010, by 0.03 degrees Celsius.”

Nine of the ten hottest Junes on record have all occurred during the 21st century, including each of the past five years, the U.S. agency said.

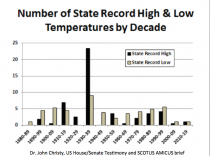

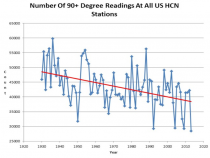

However as we have shown here, the warming is all in the questionable adjustments made to the data, with a major cooling of the past and allowance for UHI contamination in recent decades. The all time record highs and days over 90F tell us we have been in a cyclical pattern with 1930s as the warmest decade.

NOAA and NASA (which uses data gathered by NOAA climate center in Asheville) has been commissioned to participate in special climate assessments to support the idealogical and political agenda of the government. From Fiscal Year (FY) 1993 to FY 2013 total US expenditures on climate change amounted to more than $165 Billion. More than $35 Billion is identified as climate science. The White House reported that in FY 2013 the US spent $22.5 Billion on climate change. About $2 Billion went to US Global Change Research Program (USGCRP). The principal function of the USGCRP is to provide to Congress a National Climate Assessment (NCA). The latest report uses global climate models, which are not validated, therefor speculative, to speculate about regional influences from global warming. (SEPP)

The National Climate Data Center and NASA climate group also control the data that is used to verify these models which is like putting the fox in charge of the hen house. At the very least, their decisions and adjustments may be because they really believe in their models and work to find the warming they show - a form of confirmation bias.

Please note: This is not an indictment of all of NOAA where NWS forecasters do a yeoman’s job providing forecasts and warnings for public safety.

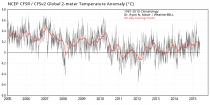

NCEP gathers real time data that is used to run the models. When we take the initial analyses that go into the models and compute monthly anomalies, we get very small departures from normal for the 1981 to 2010 base period on a monthly or year to date basis.

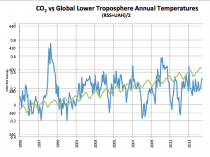

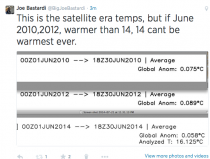

The satellite data from RSS and UAH only available since 1979 also shows no warming for over a decade (two in the RSS data). It needs no adjustments that NOAA claims are required for station and ocean data.

This government manipulation of data may be simply a follow up to the successful manipulation of other government data that has largely escaped heavy public scrutiny.

Over the last 12 months, the CPI has increased 2.1%. Real inflation, using the reporting methodologies in place before 1980, hit an annual rate of 9.6 percent in February, according to the Shadow Government Statistics newsletter. The BLS U6 measure, the total unemployed, plus all persons marginally attached to the labor force, plus total employed part time for economic reasons, as a percent of the civilian labor force plus all persons marginally attached to the labor force is 12.1%.

CPI is used to adjust social security benefits and military pay and to a large degree as one factor in industry wages. if you are feeling you are falling behind, it is because the real costs of goods and services have risen more than any income or benefits you receive. That is why the GDP actually fell early this year - between the high cost of energy and food, the discretionary income for spending retail and in restaurants fell.

Unemployment fell to 6.1% according to the government but the real unemployment is much higher. Using the employment-population ratio, the percentage of working age Americans that actually have a job has been below 59 percent for more than four years in a row. That means that more than 41 percent of all working age Americans do not have a job.

The sad news is if NOAA keeps providing the government with tainted data to justify its EPA assault on our country’s only reliable energy sources, inflation will skyrocket and unemployment will follow.

_thumb.png)