It is summer in the Northern Hemisphere again and the mainstream media in the United States are shouting once again that the summer heat is being driven by anthropogenic global warming. Is it?

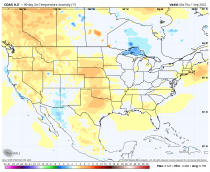

We recognize that climate changes because climate always changes. Different characteristics may be in place during one year that make it warmer, or colder, than other years. This year, we are experiencing our third consecutive year of La Nina - a substantial cooling of the waters in the central Pacific Ocean due, in part, to a significant increase in winds across the tropical Pacific Ocean. Changing the surface temperature of this large area of tropical waters creates changes in upper atmospheric weather patterns that affect us here in the United States. This year is the strongest La Nina of the recent three-year pattern.

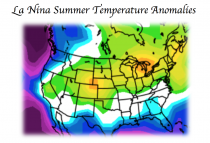

According to Joe D’Aleo of Weatherbell, strong La Nina events have caused hot and dry conditions across the central United States and into the Eastern Seaboard. So, yes, this is what we are experiencing and scientists know exactly why we are experiencing it.

Here is the long term summer average for La Ninas

Here was 2022:

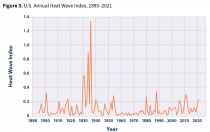

Despite the heat, we are not experiencing the warmest period in all of human history. In fact, we are not experiencing the warmest period in even the last century. A quick perusal of the website of the Environmental Protection Agency (https://www.epa.gov/climate-indicators/climate-change-indicators-heat-waves ) - not an organization one would interpret as being a member of the ‘climate denier’ posse - shows that the United States Annual Heat Wave Index was five times higher in the 1930s (i.e., the Dust Bowl era) than at any time between 1895 and 2020. Using data from the US Global Change Research Program (an organization that I briefly headed), the index describes trends in multi-day extreme heat events across the contiguous 48 states. And if we look at the last eighty years (i.e., the post-Dust Bowl era), no trend exists in this Heat Wave Index.

One thing science can say is that the heat we have been experiencing has been caused by the onset of summer and it will diminish as autumn sets in.

David R. Legates, Ph.D. (Climatology), retired Professor of Climatology and Geography/Spatial Analysis at the University of Delaware, is Director of Research and Education for The Cornwall Alliance for the Stewardship of Creation.

It’s hot. Real hot. Heat waves in the United States surely must be the most visible and impactful sign of human caused climate change, right? Well, actually no. Let’s take a look at what the U.S. National Climate Assessment and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change say about heat waves in the United States. What they say may surprise you.

Before proceeding, let me emphasize that human-caused climate change is real and significant. Aggressive policies focused on both adaptation and mitigation make very good sense. So too does being accurate about current scientific understandings. The importance of climate change does not mean that we can ignore scientific integrity - actually the opposite, it makes it all the more important. So let’s take a close look at recent assessment reports and what they say about U.S. heat waves.

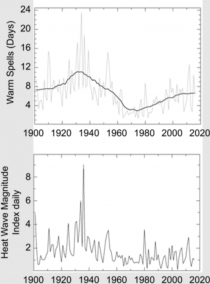

The figure below comes out of the most recent U.S. National Climate Assessment (NCA). It shows the frequency (top) and intensity (bottom) of heat waves in the U.S. since 1900. The bottom figure is actually based on a paper that I co-authored in 1999, which serves as the basis for an official indicator of climate change used by the Environmental Protection Agency.

US heat wave frequency (top) and intensity (bottom) since 1900, from the Fourth U.S. National Climate Assessment. Source; USNCA 2017

There are a few things that jump out from these figures. One is that heat waves of recent decades have not reached levels seen in the 1930s, either in their frequency or intensity. The NCA observed that the IPCC (AR5) concluded that “it is very likely that human influence has contributed to the observed changes in frequency and intensity of temperature extremes on the global scale since the mid-20th century.” But at the same time, the NCA also concluded,

In general, however, results for the contiguous United States are not as compelling as for global land areas, in part because detection of changes in U.S. regional temperature extremes is affected by extreme temperature in the 1930s.

The more recent IPCC AR6 concurred. The complex figure below (which I consolidated from the even more complex IPCC AR6 Figure 11.4) indicates low confidence (~20%) for the detection of trends in extreme heat and the attribution of those trends to human causes for both central and eastern North America (CNA and ENA). In western North American (WNA) detection is judged likely (>66%) but with low confidence in attribution.

Annotated version of IPCC AR6 Figure 11.6, showing confidence levels in detection and attribution for extreme heat, cold and precipitation for 3 regions in North America, West, Central and East. Source: IPCC 2021

The extreme temperatures of 1930s present a challenge for the detection and attribution of trends in heat waves in the United States. That means that consumers of climate reporting need to have their antennae up when reading about heat waves. It is true that if analysis of data begins in the 1960s, then an increase in heat waves can be shown. However, if the data analyses begins before the 1930s then there is no upwards trend, and a case can even be made for a decline. It is a fertile field for cherry pickers.

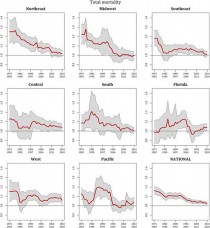

Even though U.S. heat waves have increased since the 1960s, societal vulnerability has decreased over that time. The figure below presents mortality risk in “extreme heat events” across the U.S. since the 1970s, showing an overall decline. This is good news, because it shows that the climate can become more extreme, but society has significant adaptive capacity.

Relative risk by region for total mortality on “extreme heat event” days versus non-extreme heat event days. National total is shown in the bottom right figure. Source: Sheridan et al. 2021

Make no mistake, looking to the future, the IPCC projects an increase in heat waves around the world, including in the United States. Here is what the IPCC projects for the future:

In summary, it is virtually certain that further increases in the intensity and frequency of hot extremes, and decreases in the intensity and frequency of cold extremes, will occur throughout the 21st century and around the world. It is virtually certain that the number of hot days and hot nights and the length, frequency, and/or intensity of warm spells or heatwaves compared to 1995-2014 will increase over most land areas. In most regions, changes in the magnitude of temperature extremes are proportional to global warming levels (high confidence).

How bad things get is a function of how quickly mitigation occurs. Achieving net-zero carbon dioxide is thus not about the weather this year or next, but about what happens later this century.

But regardless how fast we achieve net-zero carbon dioxide, there is good reason to believe that the societal impacts of extreme heat are manageable, and across different scenarios. For instance, according to the World Health Organization, even with increasing heat waves, mortality does not have to increase. Assuming adaptative responses (like air conditioning), the WHO concludes that future “attributable mortality is zero.” The importance of adaptation to reducing vulnerabilities to extreme heat is a robust finding across the literature.

The climate is changing, there is no doubt. In many places around the world the signal of these changes has been observed in the occurrence of heat waves. But the United States is not among those places—not yet.

But so what? If climate change is real and responding to it is important, why does it matter if we incorrectly attribute today’s weather to climate change? Maybe such incorrect attribution will be politically useful?

I can think of two reasons why it matters.

First, our assessment of risk can be skewed. If we think this week’s heat wave is a novel event juiced by climate change, rather than within the bounds of observed variability, then we are fooling ourselves. If electrical grids fail and people die this week, that will mean that we are not even prepared for the present. We need only look back to the 1930s to understand that we are also not prepared for the past, much less a more extreme future. Casual claims of detection and attribution can mislead.

Second, sustained support for action on climate will require also sustaining public and policy maker trust in science and scientific institutions. Claims that go well beyond scientific understandings place that trust at risk. A scientific consensus doesn’t exist only when it is politically useful - it also exists when it is politically unwelcomed. Accurately producing and reporting on scientific assessments surely helps to foster trust in experts and the institutions that they inhabit.

The scientific community and the journalists who report on its findings would do well to call things straight, rather than make a mockery of climate science by quickly claiming that every weather event that just happened was due to climate change.

See here even more recent mortality data that suggests cold is the real danger and killer.