Sabina Manea, UK Guardian

He wears a fine cloak, sword at his side, clearly a gentleman of standing. Behind him, representatives of the church expectantly peer out of heavy fur-trimmed garb. Once the money is paid (and it is, as always, a substantial sum), the gentleman’s transgression, be it on the battlefield or in the local bawdy-house, will be forgiven. This is how indulgences were bought and sold in the 16th century all over Europe. The Catholic church would dispense whatever forgiveness was necessary in return for cold cash, saving many tortured souls from eternal damnation.

Carbon trading does a similar job, whereby money thrown at developing countries can somehow absolve polluters from their sins against the planet. In a bid to encourage companies to reduce pollution and fight climate change, they are forced to buy credits to cover their annual emissions. The less pollution they produce, the more unused credits they can sell back in the market. Even better, people like you and me can get involved too. Flying to Barcelona for the weekend? Just click the offset carbon emissions button, and wipe away any guilt.

Carbon credits can be traded in the EU’s emissions trading scheme (ETS), but unlike other commodity markets, it’s not clear that carbon credits are tied to something that will have value tomorrow, or next year. Can the credits be owned, like a piece of property, or can they just disappear into thin air?

And disappear they may. The entire EU trading system was shut down last Wednesday, with credits worth 28m Euros missing following a series of highly effective cyber attacks that have plunged the still emerging carbon market into chaos. To make matters worse, the EU’s ETS is a serial victim; eco-activist hackers shut down the EU carbon exchange website only six months ago. The European Commission’s decision to suspend trading was taken in the wake of break-ins into online accounts in a number of European countries, with the Czech Republic being the latest casualty. The chances of recovering the stolen credits are slim, even more so once the criminals have sold them on. Unlike the money paid for indulgences, carbon credits are nothing more than records in an online account.

Where this leaves the man in the fine cloak is unclear. Those who dabble in the carbon market are vulnerable - whether industrial plants governed by the EU trading scheme or financial speculators wanting a piece of the carbon action. They thought they were buying real goods like oil or gas, which don’t just exist on a computer screen. Right? Wrong.

Whether the market participants actually own the credits like any other piece of private property, or whether hackers sitting in their bedrooms can just wave their wand and make them disappear, is something that the EU ETS is strangely silent on. This is despite the fact that the carbon market has grown to gargantuan proportions – worth 92bn Euros and accounting for 7bn tonnes in 2010 - and is the fastest-growing commodity market in financial history. But oil and gas are not hot air, and cannot be dissolved by a snap of the fingers (or a click of the keyboard). If the carbon market is to function effectively, its participants need to know what their rights are when they get involved in carbon trading. Simply issuing rights in air which may never be seen again is not good enough, and the commission should start addressing the dangers of a Pandora’s box that’s lying wide open.

On the other hand, if Europe were genuinely concerned about the environment, why should we cry over a few lost credits? Fewer credits in the market could do wonders for the environment, but would wreak havoc on financial markets, which could come tumbling down. But if millions of stolen credits flood the market, this won’t help in the battle against climate change. It may be time to think about scrapping carbon trading altogether. The commission should have thought of these problems when peering out of its fur-trimmed garb and pocketing the cash.

See more here.

By Andrew Bolt, Herald Sun

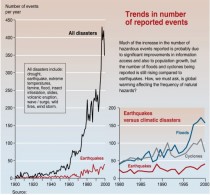

Wow. This world’s mad climate sure has got dangerous, if you believe this graphic from the warmist United Nations Environment Program (chart below, enlarged here).

Its Trends in Natural Disasters web page asks:

The statistics in this graphic reveal an exponential increase in disasters. This raises several questions. Is the increase due to a significant improvement in access to information? What part does population growth and infrastructure development play? Finally, is climate change behind the increasing frequency of natural hazards?

The answers to the first two questions are, of course, “in large part” and “a lot”, as Professor Roger Pielke Jr and Dr Indur Goklany’s work (see) suggests.

But then the UNEP blithely goes on to assume there is indeed “increasing frequency of natural hazards”. But, as hauntingthelibrary notes to its astonishment, the UNEP’s graphic suggesting this rise starts in 1900, when (if you believe it) we had close to zero natural disasters, followed by none at all the following year.

Can this be remotely likely?

Again, UNEP does hint on its graphic the obvious explanation: that we don’t have “access to information” about disasters then that we do these days, when the whole world learns instantly about a flood in Pakistan or an earthquake in Baku.

But, wait. There is one other factor to consider that isn’t canvassed by the UNEP. It’s that the researchers responsible for this graphic didn’t even bother to properly check what natural disasters there have been in 1900 and 1901 that might contradict their preferred theory that climate change is making the weather wilder.

My evidence? It’s that with just half an hour of internet searching I have found several obvious natural disasters that clearly weren’t all counted on a graphic that is woefully, incompetently incomplete. They include some far more devastating that anything that’s occurred recently:

The deadliest natural disaster in U.S. history was the hurricane that ripped into the rich, port city of Galveston, Texas, on September 18, 1900. The category 4 storm devastated the island city, killing 1 in 6 residents and destroying most of the buildings in its path.

And:

In 1900, drought in India blamed for 250,000 to 3 million deaths.

And:

The Yellow River had flooded again in 1898, and in 1900 northern China suffered a severe drought. Some religious Chinese blamed the natural catastrophes on the foreign religion in their country.

And:

In Buenos Aires, Argentina, a heat wave [in 1900] continued into its second day. The New York Times reported that “There were 219 cases of sunstroke here Sunday, of which 124 cases were fatal. The thermometer on Saturday registered 120 degrees in the shade, with 93 of 120 cases fatal.”

And:

1900: The early part of this year saw one of the most complete monsoon failures in the north of Australia, especially in normally wet Cape York Peninsula where the year proved the driest on record at many stations. In February, a major heatwave and dust-storms hit southeastern Australia.

And:

July 1901 saw high temperatures in the Middle West [of the US] that resulted in 9,508 heat deaths.

And:

Ukraine has experienced years of famine...Crop failures and hunger led to great unrest among the peasantry in 1901-07 and stimulated emigration.

And:

But we know that [Australia’s] Federation Drought was especially wretched, wreaking some of its worst, most heartbreaking havoc between 1901 and 1902.

And:

Minor flooding occurs in [Tasmania’s] Huonville on a regular basis...Severe floods occurred in 1901…

And:

An almost 110-year-old record of river flow was broken when 1.034 million cusecs of water passed the Chashma barrage [in Pakistan] on Sunday afternoon. The flood has played havoc with lives and property in upstream Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Punjab. An irrigation expert told Dawn that the highest flow recorded previously at the point was in 1901 when it reached about 900,000 cusecs. A large part of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa had been affected at that time as well.

And:

Kelut volcano has been the location of some of Indonesia’s most deadly eruptions… In 1901 ash fell at Jakarta and Serang 650 km from the volcano.

And:

In 1901 and 1902, ‘famine’ is reported from [Papua New Guinea’s] Rigo District and Goodenough Island, a ‘complete crop failure’ was reported from Milne Bay and the sago swamps at Cape Nelson burned.

See post here.

Green Tech Media

He warns investors, “Run like hell when you hear ‘green jobs, green economy, double bottom line or carbon tax.’”

Palm Springs, California—T.J. Rodgers is the Founder and CEO of Cypress Semiconductor, a force in Silicon Valley, an early equity investor in SunPower and a vintner. He spoke on Thursday morning at the CleanEdge/IBF cleantech investor forum and was introduced as “an unabashed free-market capitalist.”

Rodgers is a wry, in-your-face speaker. He walked into the lions’ den of green investors and environmentalists at this event to debunk the “religion of climate change” and warn the crowd to not get too reliant on government subsidy programs.

He does not accept human-induced global warming as reality nor the data of global warming adherents.

“Run like hell when you hear ‘carbon tax’”

Rodgers acknowledges that he has a conflict of interests in discouraging dependence on subsidies—solar subsidies have allowed SunPower to provide a 22.4 to-1 ROI for Cypress’ investors. More subsidies mean more money for SunPower and its investors. That said, he provided the audience with some advice:

Do not rely (for long) on government funding or subsidies.

Be a global warming skeptic (Rodgers most certainly is).

“Run like hell” when you hear the terms “green jobs, green economy, double bottom line or carbon tax.”

Believe in the free market and freedom of the individual.

Believe in the First Amendment, the Fourth Amendment and the Tenth Amendment.

Hanging over Rodger’s office desk is a letter from Milton Friedman who also advised Rodgers, “Get everything they [shareholders] are legally entitled to and still argue for an end to government subsidies.”

The SunPower Story

We take a break from politics and religion to briefly cover Rodgers’ role in the SunPower story. Rodgers knew SunPower’s CEO Dick Swanson in the 1970s—they were in the same PhD program at Stanford University.

Rodgers recognized the value of Dick Swanson’s high efficiency solar cells early on. Despite carpeting the roof of Cypress with 14 percent efficient BP solar panels in 2000, the roof only provided 33 percent of the building’s electricity. The 50 percent efficiency improvement promised by Swanson’s back-contact silicon cells would have provided 50 percent of the building’s power.

But the Cypress board of directors was not interested in funding Swanson’s struggling SunPower, so Rodgers wrote a personal check—the “best check he’s ever written,” for $750,000. As mentioned, that check yielded a huge return on investment and created one of the larger solar firms, now competing in the global market.

Rodgers made the important point that, “This is not the semiconductor industry.” Solar “is on a big scale with tons of silicon a day coming through the front door,” adding, “It’s not people in bunny suits—it’s a ton of silicon on a forklift.”

He said that solar requires “an order of magnitude improvement in price and throughput compared to semiconductors,” and that “We can’t afford any semi equipment—we use upgraded PCB equipment.”

As for the concept of green jobs, Rodgers insisted that “green jobs are almost all offshore—you ain’t gonna make them in Fremont, just ask Solyndra.”

He questioned the sense of Germany installing solar panels, considering their solar resource, but was happy to have Germany as a SunPower customer.

Rodgers On Global Warming

And now back to religion.

Rodgers cited surveys that indicate that the average consumer does not care about global warming. He railed against environmentalists converging on the climate talks in private jets and limousines, calling environmentalism “a secular religion, a non-god-based religion.” He also chastised the press, saying, “The press is uncritically on their side.”

Rodgers said, “Attacks on free markets are not new.” He quoted from Paul Ehrlich’s book The Population Bomb, with its doomsday scenarios that could only be remedied by a “coercive utopia” with “socialism replacing free markets,” and “altruism replacing individuality even in family matters.” Ehrlich’s predictions concerning global starvation, over-population and escalating commodity prices have turned out to have been patently wrong and cannot survive critical inspection.

Rodgers spent a considerable portion of his presentation examining and in some cases debunking the data from Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Truth and the data from the IPCC, The International Panel on Climate Change. Here are some of his points. [I will try to post his presentation shortly.]

“Al Gore’s movie An Inconvenient Truth was politics, not science”; Rodgers challenged the facts and interpretations of the movie at length. He noted the rise of CO2 in the atmosphere but challenged the causality of temperature rise and increase in CO2. He suggested that the rise in CO2, in some cases, lagged temperature rise.

Rodgers suggests, “It is not clear that 380 ppm of CO2 is bad,” adding, “Why would you pick 280 ppm as the correct number?” He also asked audience members to ponder whether the world in a high ppm environment might actually fare better.

He pointed out that IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) data was less than rigorously vetted and, in some cases, crucial trends such as the medieval warming period were either glossed over or ignored.

Hurricanes and extreme weather are not increasing.

Antarctic ice is getting thicker, not thinner.

There is a growing body of scientists questioning the evidence of global warming.

Mr. Rodgers’ incendiary talk was ill-received by many in the large, green-leaning crowd—there was some less-than-complimentary post-speech chatter. I’m reasonably sure that Rodgers doesn’t care about the critique from these “higher life forms” as he referred to people with elitist world views. Rodgers also quoted H.L. Mencken, the Sage of Baltimore, which warms my heart.

I am not able to do full justice to Rodger’s logic and rhetorical style in the confines of the article but will look to obtain the presentation from him and post it online. Read post here.