by Chip Knappenberger

“The global temperature “savings” of the Kerry-Lieberman bill is astoundingly small - 0.043C (0.077F) by 2050 and 0.111C (0.200F) by 2100. In other words, by century’s end, reducing U.S. greenhouse gas emissions by 83% will only result in global temperatures being one-fifth of one degree Fahrenheit less than they would otherwise be. That is a scientifically meaningless reduction.”

Senators John Kerry and Joseph Lieberman have just unveiled their latest/greatest attempt to reign in U. S. greenhouse gas emissions. Their one time collaborator Lindsey Graham indicated that he did not consider the bill a climate bill because “[t]here is no bipartisan support for a cap-and-trade bill based on global warming.” But make no mistake. This is a climate bill at heart, and thus the Kerry-Lieberman bill sections labeled “Title II. Global Warming Pollution Reduction.”

So apparently someone thinks the bill will have an impact on global warming. But those someones are wrong. The bill will have no meaningful impact of the future course of global warming.

That is, unless the rest of the world - primarily the developing nations - decide to play along.

In fact, the United States and the rest of the developed countries have little role to play in the future course of global warming except as developers of new energy technologies and/or as guinea pigs of making do with less fossil fuels.

Our attempts at domestic emissions savings will have only minimal direct climate impact, but instead they will serve as an example for the developing world of what, or what not, to do. So if Kerry and Lieberman were interested in directly tackling the climate change issue, they would be working with China’s National People’s Congress to draft legislation to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, not the U. S. Senate.

But, everyone already knows this, as we demonstrated the non-impact of U.S. emissions reduction efforts in Part I and Part II of our analysis of last summer’s Waxman-Markey offering. And as far as the global warming goes, Kerry-Lieberman’s The American Power Act of 2010 is similar to Waxman-Markey’s American Clean Energy and Security Act of 2009.

Kerry-Lieberman’s domestic greenhouse gas emissions reduction schedule is 17% below 2005 emissions levels by 2020, 42% below by 2030, and 83% below by 2050. Compare that to Waxman-Markey’s 20% reduction in emissions (below 2005 levels) by 2020, 42% by 2030, and 83% by 2050. Except for a bit of relaxation of near term targets, the bills’ long-term intentions are identical.

The impact of this slight emissions difference on the resulting future global temperature savings is not manifest until the third digit past the decimal point - in other words, thousandths of degrees C. Climatologically, in other words, the bills are identical.

As in our prior analyses, we use the same techniques employing a climate model simulator to derive global temperature (and sea level) projections from the greenhouse gas emissions scenarios. We use the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) “business-as-usual” scenario (A1B) as the baseline, and then modify it to take into account the Kerry-Lieberman emissions targets for the U.S.

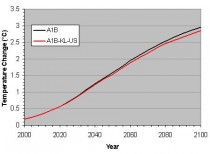

Figure 1 compares the global temperature projections from the business-as-usual (BAU) scenario with the Kerry-Lieberman adjustments. The BAU scenario produces a temperature rise (over the 1990 global average temperature) of 1.584C by the year 2050 and 2.959C by 2100. The Kerry-Lieberman adjustments produce a temperature rise of 1.541C by 2050 and 2.848C by 2100.

Figure 1. Projected global temperature rise from the IPCC’s business-as-usual (A1B) scenario (black curve) and the Kerry-Lieberman emissions scenario (red curve).

The global temperature “savings” of the Kerry-Lieberman bill is astoundingly small - 0.043C (0.077F) by 2050 and 0.111C (0.200F) by 2100. In other words, by century’s end, reducing U.S. greenhouse gas emissions by 83% will only result in global temperatures being one-fifth of one degree Fahrenheit less than they would otherwise be. That is a scientifically meaningless reduction.

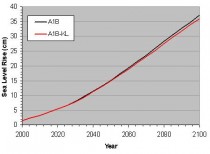

Figure 2 shows that the impacts on future sea level rise projections are equally insignificant. Instead of a projected sea level rise of 15.1cm by 2050, the Kerry-Lieberman bill produces a rise of 14.9cm. By 2100, the BAU projected rise is 37.1cm and the Kerry-Lieberman rise is 36.0cm. A century’s end sea level rise savings of 1.1cm, or 0.43 inches. Too small to be of consequence.

Figure 2. Projected global sea level rise from the IPCC’s business-as-usual (A1B) scenario (black curve) and the Kerry-Lieberman emissions scenario (red curve).

As I mentioned previously, the real impact of the Kerry-Lieberman bill only emerges if it is applied to the rest of the world, and in particular the world’s developing nations.

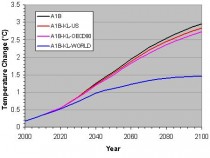

Figure 3 shows the global temperature projections from the BAU scenario, along with the successive adherence to the Kerry-Lieberman emissions schedule by the U.S., the OECD90 countries (industrialized countries including the U.S., Western Europe, Australia and Japan), and the entire world. Basically, unless the developing world comes on board, the world’s future temperature pathway will be largely unchanged.

Figure 3. Projected global temperature rise from the IPCC’s business-as-usual (A1B) scenario (black curve) and the Kerry-Lieberman emissions scenario as applied to the U.S. (red curve), the OECD90 countries (magenta curve), and the entire world (blue curve).

Granted, all my numbers may change a bit if different assumptions are made about the baseline scenario, the particulars of international cooperation, or the various parameters of the climate model simulator (for example, I used a climate sensitivity of 3.0C). But the bottom line will remain the same-climatologically, the Kerry-Lieberman American Power Act, in and of itself, is a meaningless bill. To make it effective, it must involve the world’s developing counties. Read more here.

By Iain Murray

Three separate events late last year knocked the air out of international climate alarmism. Combined, they put the kibosh on global warming legislation in the United States for the foreseeable future. Now the only ones keeping such legislation alive are a handful of powerful special interests. Contrary to what you normally hear, big business is pushing, not opposing, climate legislation.

The first event was the scandal that became known as “Climategate.” A public release of emails between climate scientists, at the University of East Anglia’s Climate Research Unit, showed clear evidence of collusion to subvert the scientific process for political ends. The emails also showed those scientists engaging in a cover-up in possible violation of Britain’s Freedom of Information laws. Polls following Climategate showed that it shattered public trust in climate science.

Climategate was followed by a series of embarrassing admissions that some conclusions in the reports from the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change were based on unsupported assertions by some scientists and on claims from non-peer-reviewed ("grey") literature. As a result, climate alarmists’ main argument - the appeal to scientific authority - no longer carries much weight. Attempts to whitewash Climategate have fallen flat and on deaf ears.

Finally, the U.N. climate talks in Copenhagen ended in failure. After years of touting the talks as the route to a bigger, better Kyoto Protocol, climate alarmists stood by helplessly as the developing world bypassed Europe and forced President Obama to agree to something very similar to the Bush administration’s climate policy. Long before Climategate, major developing countries, including India and China, had rejected binding reductions in emissions as an unjust restriction on their poverty-fighting efforts. Any attempts to sign them up to this agenda were doomed to failure from the start.

The Copenhagen talks were a turning point for international negotiations, but not in the way environmental advocacy groups expected. Previously, negotiations for a new global climate treaty had been driven by Europe, with the U.S. (and Australia in the Howard years) acting as a brake. The Kyoto Protocol was favorable to Europe, because it allowed it to bank emissions reductions that had already happened - as in, for example, Britain’s emissions reductions from its “dash for gas” in the early 1990s - well before Kyoto was signed.

Most developing countries backed the American position. So by the time of the Copenhagen summit, the gap between Europe’s position and that of the major developing countries had grown so large, that President Obama was forced to choose between them. Wisely, he chose the developing world, a decision that leaves Europe marginalized in climate negotiations. French President Nicolas Sarkozy seems to realize this, and figures the only climate policy options he has left is the threat of a carbon tariff - which could lead to a destructive trade war between North and South.

For America, the bottom line to all this is that the two strongest arguments for a global warming bill - scientific authority and international pressure - are gone. All that is left is an unseemly collection of environmental ideologues and their strange bedfellows in large companies hoping to profit from a global warming bill. For these companies and environmental groups - who joined forces in something called the U.S. Climate Action Partnership a few years ago -the various subsidies and other incentives in a global warming bill held the promise of a significant guaranteed income stream.

My organization, the Competitive Enterprise Institute (CEI), predicted this back in 2001. Professor Ross McKitrick, in a paper he authored for CEI, demonstrated how a cap-and-trade scheme for greenhouse gas emissions would actually create a “carbon cartel” which would yield significant economic gains for the members of the cartel at the expense of consumers, taxpayers, and the economy as a whole.

Today, the only major constituency lobbying for greenhouse gas legislation is this cartel, which includes companies like General Electric, Dow Chemical, General Motors and Duke Energy. In the classic formulation of Clemson University economist Bruce Yandle, they represent the self-interested “bootleggers” to the environmental groups’ self-righteous “Baptists” - two groups that lobbied for prohibition, but for very different reasons. Whether the motive is salvation or profit, the practical result is the same.

The bootleggers are now the Baptists’ only hope. Not for nothing did Sen. John Kerry (D.-Mass.) boast that his American Power Act, introduced today, was largely written by the U.S. Climate Action Partnership. That’s worth keeping in mind the next time left-wing environmentalists criticize global warming skeptics for allegedly being backed by big business. In truth, big business is backing global warming legislation and skeptics are doing their best to stop them from inflicting further harm on America’s struggling economy.

Iain Murray is Vice-President for Strategy at the Competitive Enterprise Institute (www.cei.org)

Read more at the Washington Examiner here.

See preview here.

Contacts:

Richard Morrison, 202-331-2273

Christine Hall, 202-331-2258

by Richard Morrison, CEI

Will BP and Goldman Sachs Be at Kerry’s Press Conference?

Washington, D.C., May 11, 2010 - As Senators John Kerry (D-MA) and Joseph Lieberman (I-CT) prepare to introduce their long-delayed energy-rationing legislation, the Competitive Enterprise Institute calls on Americans to remember what is really at stake: government control over energy use and massive kickbacks to favored corporations.

“The bill crafted by Kerry and Lieberman - and sometimes Lindsey Graham (R-SC) - manages to have something to harm everyone except big business special interests,” said Competitive Enterprise Institute Director of Energy Policy Myron Ebell. “Environmentalists know it will have no discernible impact on the climate, but it will reward favored companies with massive windfall profits.”

Senator Kerry has admitted that the bill was written in close consultation with the companies and industries to be regulated, including the Edison Electric Institute and major oil companies. Kerry recently remarked “Ironically, we’ve been working very closely with some of these oil companies in the last months,” referring to BP, Conoco Phillips, and Shell. This process could only be considered “ironic” by someone unacquainted with the history of special interest lobbying in Washington, D.C.

“Cap and trade regulation, far from disciplining the energy sector, is poised to become one of the greatest wealth transfers from consumers to private corporations in the nation’s history,” said Ebell. “General Electric, Exelon, BP, Goldman Sachs, and Duke Energy will make out like bandits because of provisions they have written. That’s not democracy or capitalism. It’s political corruption and crony capitalism.”

As public awareness of what cap and trade would cost American consumers has grown, the bill’s sponsors have responded not by amending their proposals, but by trying to fool the public with shifting terminology. Senator Kerry at one point renamed gasoline taxes “linked fees.” Sen. Lieberman remarked in April he was dropping the phrase “cap and trade” in favor of “emissions reduction targets,” going so far as to joke about the in-name-only difference by asking a reporter “Remember the Artist Previously Known as Prince?”

“Lieberman is not the only one playing word games,” said CEI Senior Fellow Marlo Lewis. On-again, off-again co-sponsor Lindsey Graham recently said in an interview that he no longer considers the Kerry-Lieberman legislation either a cap-and-trade bill or a global warming bill because “There is no bipartisan support for a cap-and-trade bill based on global warming.”

“So, because climate alarm and cap-and-tax are no longer polling well, Graham now pretends he can change the bill’s nature simply by rebranding it. I’ve got news for these guys,” said Lewis. “Everybody knew it was Prince even before the Artist Formerly Known As changed his name back to plain old Prince. An energy tax by any other name is just as foul.” See release here.

CEI is a non-profit, non-partisan public interest group that studies the intersection of regulation, risk, and markets.

Time to holler long and loud at the senators in your state here.

----------------

On Sunday, May 23, 2010, The U Thant Institute will host its sixth annual Ambassadors’ Luncheon at the Shore and Country Club in Norwalk, Connecticut. The keynote speaker, Nobel Peace Prize recipient Dr. Rajendra Pachauri, will give his thoughts on The Economics of Climate Change in Southeast Asia.

Here’s his 2008 lecture at the UNSW (Australia). You may find it amusing to play a “Spot the False Claims” game.

Here’s a performance by the late Tiny Tim in front of future IPCC members or today’s mainstream media, children at the time. It would qualify for a broadcast seal or award by the American Meteorology Society and perhaps Tiny Tim would be doing The Weather Channel with Heidi Cullen et al.