In this story Volcano’s Eruption Colors World’s Sunsets on Live Science, Andrea Thompson reported: “Reports of unusually fiery orange sunsets on Earth and ruby red rings around the planet Venus have popped up on the Internet in the last week.

Some skywatchers suspect that these views are being colored by the dust and gases injected into the atmosphere by the Aug. 7 eruption of Alaska’s Kasatochi volcano. The skywatchers are probably right. Kasatochi, part of the Aleutian Island chain, sent an ash plume more than 35,000 feet (10,600 meters) into the atmosphere when it erupted last month.

“This is a big ash-producing eruption,” said Peter Cervelli, a research geophysicist with the United States Geological Survey at the Alaska Volcano Observatory. During a survey of the area after the eruption, Cervelli and his colleagues found ashfall deposits more than 6 inches (15 centimeters) deep at a spot 15.5 miles (25 kilometers) away from the volcano.

The fine ash injected by a volcanic eruption into the stratosphere can be carried by winds all over the world. Sulfur dioxide spewed from volcanoes can react in the atmosphere to form sulfate aerosols (aerosols are tiny particles suspended in the air). Both ash and aerosols can scatter the sun’s rays, giving a sunset its apparent color.”

Ruby red sunsets and Bishop’s rings were also seen after the monstrous eruption of the Philippines’ Mount Pinatubo in 1991, Pfeffer added, though that eruption was on a much larger scale than Kasatochi. In fact, the ash and aerosols that spewed from Pinatubo spread across the globe and were so pervasive that temperatures in the year after the eruption were cooler than normal.”

See larger image of Kasatochi here

Icecap Note: This clearly is no Pinatubo but the sunsets suggest it has injected the aerosols into the stratosphere where it has a longer lifetime than smaller eruptions. In this story we note that climatologists may disagree on how much the recent global warming is natural or manmade but there is general agreement that volcanism constitutes a wildcard in climate, producing significant global scale cooling for at least a few years following a major eruption. However, there are some interesting seasonal and regional variations of the effects. Robock (2003) and others have shown that though major volcanic eruptions seem to have their greatest cooling effect in the summer months, the location of the volcano determines whether the winters are colder or warmer over large parts of North America and Eurasia.

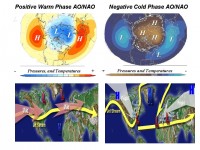

We showed that Robock (2003) and others have shown that though major volcanic eruptions seem to have their greatest cooling effect in the summer months, the location of he volcano determines whether the winters are colder or warmer over large parts of North America and Eurasia. According to Robock, tropical region volcanoes like El Chichon and Pinatubo actually produce a warming in winter due to a tendency for a more positive North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) and Arctic Oscillation (AO) - below left top and bottom. In the positive phase of these large scale pressure oscillations, low pressure and cold air is trapped in high latitudes and the resulting more westerly jet stream winds drives milder maritime air into the continents. Robock found high latitude volcanoes like Katmai (Alaska in 1912) instead favored the negative phase of the Arctic and North Atlantic Oscillations and cold winters - right side top and bottom. In the negative phase, the jet stream winds buckled and forced cold air south from Canada into the eastern United States and west from Siberia into Europe.

See larger image here

Despite the regional differences in winter, globally on an annual basis, volcanic eruptions lead to a net cooling regardless as to the volcano’s latitude.

Update: Jos De Laat of the KNMI wrote to say “we have been monitoring that one very closely. An animated image of satellite observations of sulphur dioxide (SO2) for the first ten days after the eruption can be found here (hit the reload button if the movie does not play). More satellite imagery of SO2 can be found here and here. Most of the SO2 and presumably the ash have disappeared by now. The rapid transport of the SO2 shows that most of it was transported to the upper troposphere - entering the jetstream - where it can be removed rather quickly. By using the NASA CALIPSO LIDAR instrument we were (are) able to accurately estimate the altitudes of the plumes (here and here). However, some SO2 and ashes were injected higher up in the stratosphere (15-20 km altitude) where removal takes much, much longer. A few thin stratospheric remnants are still visible in the CALIPSO data and if you look carefully also in the SO2 images. However, it appears that the majority of the plume did not enter the stratosphere, hence I presume the climatic effect will be relatively small.